There is an athlete among us, still active in competitive play, who is truly extraordinary. Indeed, there are many athletes who can be called this. But Roger Federer is uniquely extraordinary, not just because he has dominated professional tennis for so many years and won more matches than anyone else in the history of the game, but because of his attitude toward the whole endeavour of sport itself.

I am neither a sports writer nor even a sports fan. For forty years I was a dancer, dance teacher and choreographer, and as such perhaps my perspective on Roger’s athleticism is particular. Not being drawn to most sports, because the competitiveness that it thrives on is simply too obvious, nasty and occasionally brutal — and, that the customary language of war that commentators use is, for me, annoying and sometimes offensive — I see Roger Federer as someone who is beyond all this. Sports commentators are forced to find, for them, less familiar adjectives — artistic, flowing, sublime — to describe what they see. It is clear to me, and to every dancer I have ever brought to see him play, whether live or on television, that he is a kindred spirit; that there is a dancer in this amazing athlete.

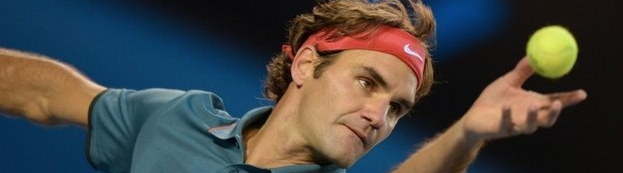

There is a light-footedness and ease to his play that is unusual. Like a dancer, he has a lightness in the air.2

For dancers, part of what we see is a body — or instrument, as we call it — that is almost perfectly aligned. This means that all the bones of his body are in their correct position creating a physical structure that allows not only for beautiful and natural co-ordination (I have never seen him appear awkward, even when missing a shot), but also a quiet ease and freedom of movement. This level of alignment usually takes close to ten years of training for a good modern or ballet dancer to attain. This Roger has naturally; in other words, he has a very well-integrated body not requiring excessive muscular development. Willful fighting in order to win simply vanishes when he is playing.

For a number of years he worked without a coach, claiming, "I knew what to do, I just had to do it."

Specifically, Roger’s open chest, revealing what I consider to be a balanced emotional nature, is another reason he can avoid the overly aggressive and sometimes ferocious attitude that many players adopt in order to win matches. (In teaching dance I have found that, especially in young men, that this type of energy created by anger is short-lived.) This balanced nature — which is also the attitude of the martial artist, who is really only in competition with himself — became especially clear to me a number of years ago watching him in a match: I noticed that when Roger relaxed, he played better; whereas when his opponents relaxed, they made errors. Many coaches know this, and other professional players are catching on to this, but Roger has always exemplified it.

The fact that there is such beauty to Roger’s game — as well as its obvious effectiveness: with all the records he has amassed — is evidence to me of another kind of player, another level of athletic intelligence and execution. At his best, I believe that, with his gifted body and alert mind, Roger truly transcends tennis.

Roger was one of the first to make the single-handed backhand so thrilling and effective. Similar to what a dancer would use, he uses the spiral of the torso.1

To make him a legend in his own time, or some sort of hero — as many media commentators desperately want to do — is a mistake. I prefer to see Roger as a model of someone in whom we can see human potential fulfilled. (Rafael Nadal said, “If I could play the way Roger does, I would. But I can’t.”) Personable, diplomatic and intelligent, Roger is respected and liked enormously by practically everyone in the tennis world today — a gentleman in a competitive sport. As a teenager he rid himself of the frustration and anger that often plague tennis players. I heard him once say that he was embarrassed by his behaviour, at the age of fifteen, throwing his racquet about.

At the age of nineteen, on the hallowed courts of Wimbledon where he beat Pete Sampras, the top player in the world at the time, Roger revealed the composure that became one of the trademarks of the Federer style. For a number of years he worked without a coach, claiming, "I knew what to do, I just had to do it."

In dance terms, this could be termed an ‘attitude’ in the air: a position in which the dancer stands on one leg (the supporting leg) while the other leg (the working leg) is raised, turned out and bent.3

Support for the body itself comes from the back, and it was Roger’s back that showed the strain last year of the previous 13 years. Being injury-free for all that time was due to the organic efficiency of his body, and, like a dancer who listens to the body, his utter respect for it: never exploiting it by playing through pain, never bullying it to get the win.

That he will not be able to play forever is something that we admirers will simply have to accept, but here he is again in 2014, free of pain, delighting and dazzling us once more. He doesn’t always win his matches now, but he continues on — doing what he loves, grateful for his gifts — bringing a thrilling elegance to the court. Roger has taught the members of the press to be more respectful of all the players, and to refrain from thinking that every time he steps on the court he must win.

When the inevitable day of his retirement does come, I, along with millions of other fans, should feel grateful that we were able to watch tennis when Roger played, one of those elite players who show us what is possible. They are our inspiration and our pathfinders who, in sport and art, have shown us how power correctly defined is not domination over others, but the complete fulfillment of personal potential. Roger Federer exemplifies this, as no other athlete I have ever seen.

He doesn’t dress this way anymore, because it was misunderstood (that he was being arrogant), but for a couple

of years Roger wore a white suit when he received the cup at Wimbledon, in respect for the history of the sport.4

There is a prince on the court

not royalty as we usually know it

but manly presence

quiet contained

seething in possibility

there is a prince on the court

he claims to be from Switzerland

but seems to be from everywhere

a universal athlete

there is a prince on the court

dazzling in his executions

he wins for all of us

who prefer play to war

there is a prince on the court

on a good day the game plays him

rather than the reverse

a leo who loves to win

grateful and warm with his opponent at the net

Yes, there is a prince on the court

His name is Roger Federer.

From Slow Words Dancing, by Patricia Beatty, Wonder Press, Toronto.

This article first appeared in The Journal of Wild Culture, Oct. 10, 2014. And Roger is still at it.

PATRICIA BEATTY has spent her life as a modern dancer, teacher and choreographer. She is the co-founder of the Toronto Dance Theatre and received the Order of Canada in 2004 for her pioneering work in modern dance. Since retiring from making new dances in 2004, she has turned to writing poetry. Her book on the art of choreography, Form With Formula: A Concise Guide to the Choreographic Process, published by Coach House Press, is in its fifth edition. Slow Words Dancing can be ordered from casakoolba@gmail.com.

PHOTO CREDITS — 1, 2, 3, 4. Top photo.

Add new comment