George Monbiot at Falmouth University, March 16, 2018.

One of the questions I'm most often asked is why don't I despair, given that my job basically consists of rolling in the excrement of humanity (and I am not just referring to my recent encounter with Piers Morgan). Yes, how do I get out of bed in the morning, considering I have to engage with all the terrible things that are going on around the world?

The truth is that, sometimes I do. I mean, there is a lot to despair over. One of the rather alarming revelations I had last year was that climate breakdown, and I call it 'climate breakdown' because calling it climate change is like calling an invading army 'unexpected visitors’ — it's such a ridiculously neutral and passive term for the existential crisis we face. Climate change is only the third most urgent environmental issue that we confront. This is not because it's become any less urgent, far from it, but because I realized that two other issues are happening with even greater speed and force than climate breakdown is happening. Those are the ecological cleansing of both the land and the sea by the food industry – the extraordinarily rapid destruction of whole ecosystems, of the species that inhabit those ecosystems, of the ecological structure and function of those places, and also, often, of the very physical resources upon which both ecosystems and human survival are based.

To give you one classic example of this, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization says that at current rates of soil loss we have 60 years of harvests left. Now, civilizations can suffer famines, wars and plagues, and they can bounce back from those disasters. But you lose your soil and there is no coming back at all; you have lost the basis for human life and much of the other life on this planet. And that's just one of the resources currently at great risk.

We interpret the world through stories because the world is too complex to interpret by other means.

So we have a multiple manifold ecological crisis meshing with an economic crisis, a crisis of patrimonial wealth. Thomas Piketty described it very well, but he called it, misleadingly, ‘patrimonial capitalism’ because actually a patrimonial capital, most of what is being secured by the 1% is wealth rather than capital, is stuff which nobody made; it's stuff which wasn't created for productive purposes, particularly land. Anyone want to hazard a guess as to how much property wealth the 1% in this country have on average, with about 600,000 people in that category? [The answer is:] 15 million pounds in property wealth. That’s where the real inequality is — it's not so much in income, it's in wealth. And that capture of wealth — alongside the capture of much of social production by the extremely rich — not only deprives other people of wealth, but also greatly distorts the whole basis of the economy. The economy effectively begins to shift from being an enterprise economy to a rentier economy: where the very rich are living off the economic rents which they extract from the rest of us, while doing almost no work.

Now, I define economic rent (and there are several different, often confusing definitions) as using your exclusive control over a non-reproducible resource in order to charge excessive fee. A classic example of this is a train journey I've just taken. I know that part of the money that I paid for my ticket will go on rolling stock and fuel and staffing costs. But a big part of that money, I don't know quite how much, but probably a fairly substantial wodge of it will go for the fact that they have me over a barrel. There's only one train company working that line and they can charge pretty well what they want for me to come down here to Falmouth. So that part of the ticket price — which represents their monopoly position — is economic rent; that is, money which they have unfairly taken from me, not for offering a service but because they've got me where they want me.

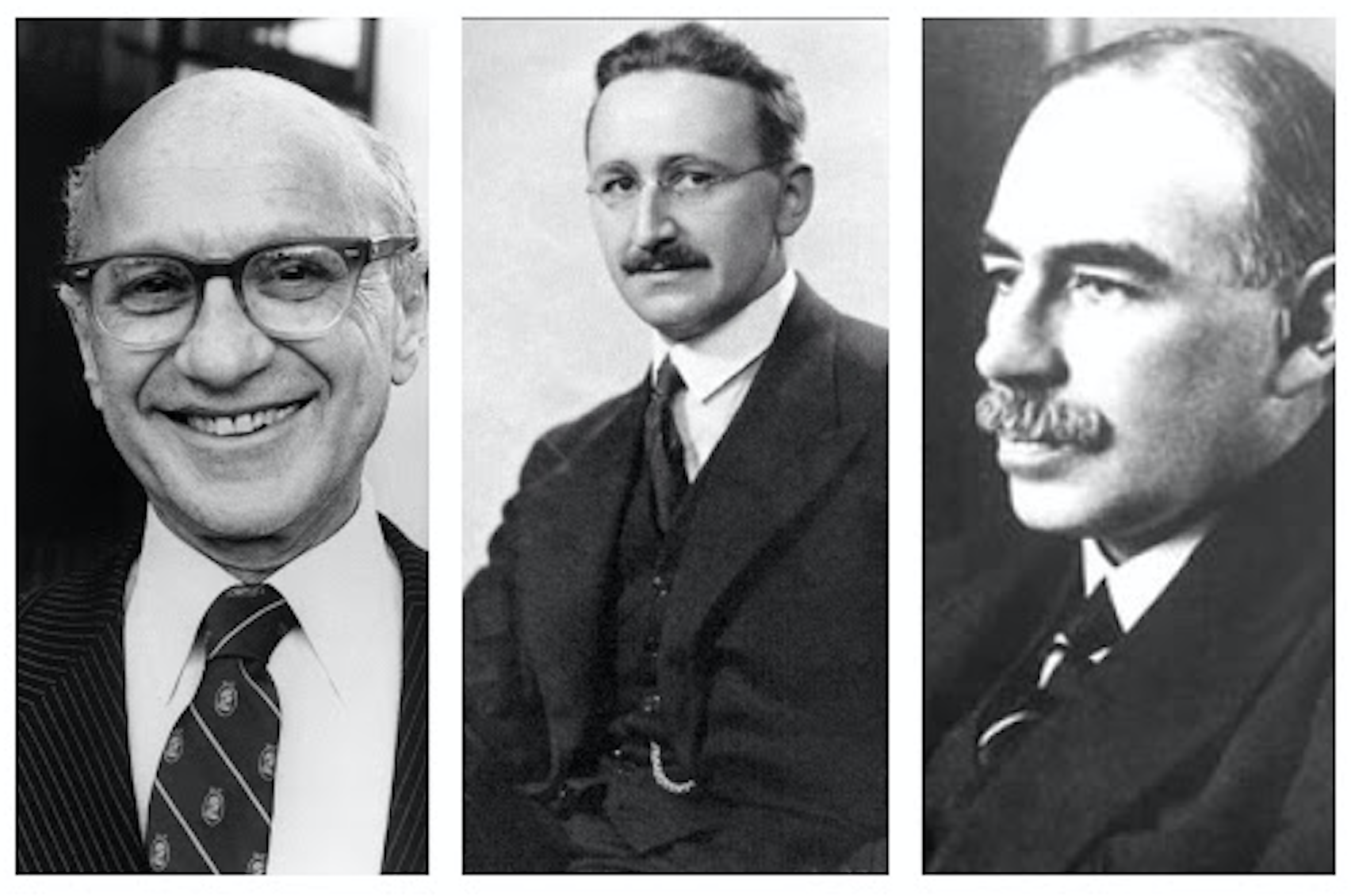

Friedman, Hayak and Keynes. "The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones." — Keynes. [o]

Now, confusing me again: When you pay rent for a home, part of that money is going to be compensating the landlord or the landlady or the company or whatever it is, the university, for the cost of buying the house and for any repairs that they're doing. But also because it is in effect a nonreproducible resource, in that, there can only be one home and one location, and that some locations are much more desirable than others. You're going to be paying over the odds because basically, again, they've got you where they want you — not least because there's a housing shortage in Britain anyway. And by this means, those who have money make an awful lot more money without having to put in any effort, and they take that money from everyone else. Far from wealth trickling down, wealth is grabbed by the very rich and accumulated.

This system of wealth accumulation has been greatly enhanced by the ideology that has led to the next crisis, which is the political crisis. And this, the dominant ideology of our times, is best called neoliberalism. The term was originally given by its founders, people like Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, who were all happy to call themselves neoliberals until suddenly they realized it was better not to call themselves anything, and just claimed that they were describing a natural system which functioned a bit like Darwinian evolution; and, that it wasn't even an economic theory they were proposing, they were just describing the world as it is.

At the core of neoliberal thought is the notion that our relationships should be transactional, that we exist in relation to each other through buying and selling, and that this process of buying and selling — of treating the whole of society as if it were a corporation, in effect — determines who the natural winners are and who the natural losers are. It creates what they say is a natural hierarchy, a scala naturae [great chain of being] of virtue, and those who have striven and worked hardest, they become the very rich, and those who are deviant and undeserving, they become the very poor. And any political or social process which tries to interfere with the discovery of this natural hierarchy of winners and losers is illegitimate. That applies to taxation, that applies to regulation, that applies to trade unions. In fact, that applies to politics in general.

Politics is determined to be an illegitimate sphere by neoliberalism because it's the market: this transfer of wealth between people which is the only means by which decisions should be made. This market, well, it turns out not to be a force of nature, it turns out to be something controlled by human beings and controlled primarily by those who've got the most money. And so what this sort of impersonal force, which was meant to be making these decisions in practice, turns out to be actually a highly personal force of oligarchs who are using the opportunity of escaping from politics, escaping from democracy to massively enrich themselves; and by cutting those public protections which defend workers, which defend citizens, which defend the living world. By cutting taxes and by destroying trade unions they have managed to free themselves from democracy and free themselves to become immensely wealthy, which is what is driving the tremendous growth in inequality that we see today; and, also driving the cycle of patrimonial wealth accumulation that, once you've got money, you can make much more, and there's nothing to stop you if politics can no longer intervene.

In turn, this creates a political crisis because if politics says, “Our role is to stand back.” If the government says, “Our role is no longer to govern.” If the state says, “We must shrink the state,” then there is no means by which social outcomes can be altered. Social mobility stalls, the redistribution of wealth stalls, and politics can no longer change what happens in people's lives, so it therefore becomes irrelevant to them. People perceive politics as being the Yaba of a remote elite going on above their heads, rather than being something which makes any sense to their lives at all. So people then turn to an anti-politics, a politics characterized by symbols and slogans and sensation rather than by argument and by fact and by rational discourse – a politics which says, “Come and belong to us and that's all you need to do. You will be the elect, you will be the dominant people, and you will crush the losers, the undeserving.”

This is what we see with the rise of demagoguery taking place now around the world. It’s not just Trump, it's Modi in India, it's Duterte in the Philippines, it's Erdoğan in Turkey, it's Orban in Hungary, and many others besides. There's this new age of demagoguery that seems to be beginning and it could very easily start to shade into a new fascism. We're already beginning to see the stirrings of fascism with its virulent racism and misogyny and, really, hatred of all difference, hatred of all gentleness, hatred of all kindness. We’re starting to see something I never thought I would see in my lifetime: the resurgence of this smashed and discredited idea which is now — because of the political vacuum, because of a complete failure of politics to provide answers for people, because of the grip of neoliberalism — returning.

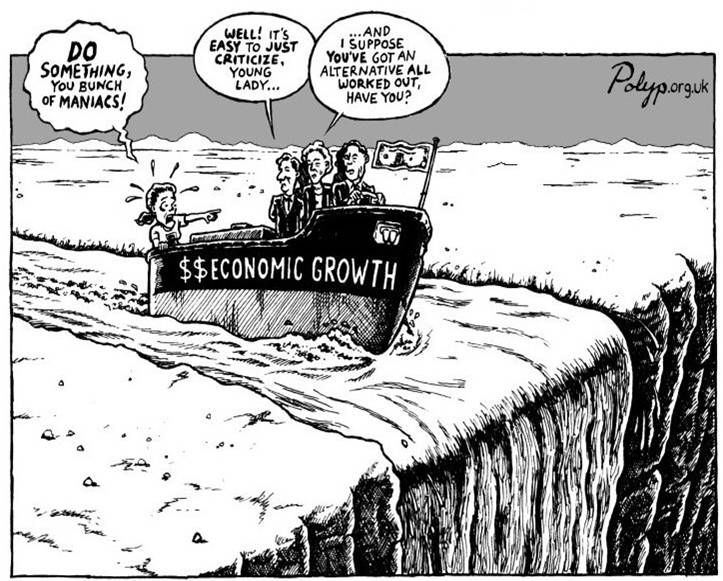

The neoliberal impulse at work. [o]

So we have a crisis on many levels and, in many ways, this crisis interlocks with neoliberalism; it’s driving environmental destruction as well because when you strip away public protections for the living world, there's nothing to stop them. Why wouldn't they chop down the forests? Why wouldn't they sieve all the fish out of the sea, if no one's saying you can't? And of course, the economic and political crises reinforce each other in a vicious spiral.

So you can look at all that and say, yes, there's plenty of cause for despair. But, on the whole, I do not despair (just sometimes I have my moments). I do not despair because of the fundamental recognition that's driven me for many years, which is that political failure is at heart a failure of imagination. If you are staring at the wall and you cannot see any cracks in the wall, it's not because the cracks aren't there. In politics, there's always cracks in the wall, it's because you're not looking at it right. Sometimes you have to stand back, look at it in a different light, use your imagination, expand your mind, then you will start to see those cracks. And this conviction for me has been reinforced over the past two or three years by four observations, and I don't claim that they're original to me (possibly one and a half are, sort of). But others are commonplace, and these strongly suggest that there is everything to play for.

1. BIG POLITICAL NARRATIVES

The first of these observations is that it is not political parties or political leaders who run the world and create major political change, but big political narratives. For example, if you look at the history of the past 70 or 80 years, you'll find it roughly split down the middle between two big political narratives: Keynesian social democracy and neoliberalism. And at the height of both of those doctrines, they became almost universal. When Keynesian social democracy was the dominant doctrine — particularly during what the French call the Trente Glorieuses, between 1945 and 1975 — in Richard Nixon's words, “We are all Keynesians now.” It became the common sense, right across politics. It didn't matter whether you were a Democrat or a Republican, Labor or Conservative; it didn't matter what your roots were, what your colors were, you became a Keynesian. And then when that ran into trouble in the late 1970s and the neoliberals turned up, over the course of a few years almost everyone became neoliberal — New Labor and Democrats. Again, it didn't matter what your supposed political persuasion was, it was the narrative that dominated.

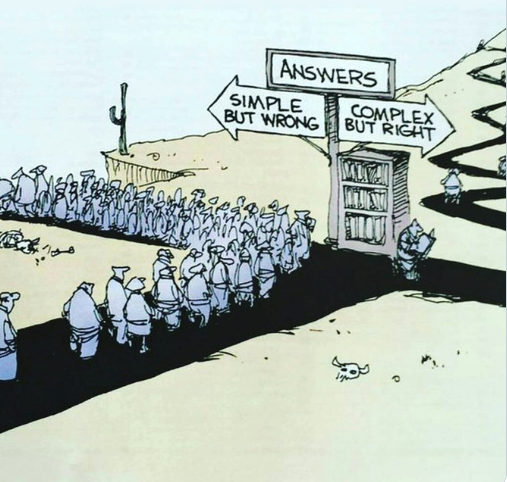

Easy alternatives. [o]

Perhaps there's nothing surprising about this, because we are fundamentally creatures of narrative. We interpret the world through stories and we do so because the world is too complex to interpret by other means. The sense we seek is not the sense that mathematicians or scientists or philosophers recognize, the sense we seek is narrative sense. Instead of facing this stream of data which is coming at us all the time, and saying, “Right, the data on that side says this and the data on that side says this, now, what do I think the probability of this being correct is?” We just can't work like that, there’s too much happening. Our minds are too complex, the minds of other people are too complex. We can't process all the stuff which is going on inside us and around us — in terms of data gathering and data processing — so we need a heuristic, a shortcut, and the story is a shortcut that we have used for hundreds of thousands of years to make sense of the world. So, what we're listening for is: does this have a beginning and a middle and an end? Does it progress as I would expect it to progress? Does it show us how we got to where we are, where we now stand, where we're likely to go, what it's going to be like when we get there? Is there a hero, do they triumph? These are the narratives that we're listening out for. You cannot take away someone's story without giving them a new one. If you try to confront a story with facts and figures, they will just bounce off you. We bounce off it because the only thing that can displace a story is a story.

2. THE RESTORATION STORY

And this leads to the second observation, which becomes more interesting, which is that though Keynesian social democracy and neoliberalism are polar opposites to each other, they use exactly the same narrative structure. This is the structure I call the restoration story. I believe that our minds are tuned, not just to narratives in general, but to particular structures, and this one is a very powerful structure. It goes as follows: the land has been thrown into disorder by powerful and nefarious forces working against the interests of humanity. But the ‘hero’ of the story — who might be one person or a group of people or even an institution — will take on, against the odds, the powerful and nefarious forces, overthrow them and restore order to the land. It's the Lord of the Rings story, it's a Narnia story, you've seen it a thousand times, and it turns out that both of those stories use that structure.

So, Keynesian social democracy says, “the land has been thrown into disorder by the powerful and nefarious forces of the economic elite who, through the 19th and early 20th centuries, accumulated all the wealth, all the social production for themselves, depriving other people of their means of subsistence, throwing them into destitution and debt, destroying consumer demand, thereby undermining the economy and causing the Great Depression. But the hero of the story, the enabling state supported by the working and middle classes, will fight back against these powerful and nefarious forces, will tax them heavily, will use that money to spend back into the public sphere, creating robust public services and strong social safety net, and in doing so will create circulation and employment, which in turn will create consumer demand, which in turn will create wealth — and order will be restored to the land.

The neoliberal story says: The land has been thrown into disorder by powerful and nefarious forces in the form of the collectivizing state. And even though it may seem benign in its first instances — like in the British welfare state or the American New Deal — it inevitably leads us down the road to serfdom because that very process of trying to manage people as a whole, through public services and the welfare state, will lead to the suppression of individuality and freedom and opportunity, and that leads inexorably to totalitarianism in the form of Stalinism or Nazism. But the hero of the story, the freedom seeking entrepreneur, will fight these powerful and nefarious forces and, by using the market and by opening that sphere and pushing back against the collectivizing tendencies of the state, will liberate people and allow them to express individuality and opportunity of the kind they haven't had during this era and this will, therefore, restore order to the land.

3. THE DOMINANCE OF THIS STRUCTURE

These two opposite narratives with the same narrative structure led me to the third observation: just about every successful political or religious transformation that has ever been has used that narrative structure. The restoration story is absolutely fundamental, and without the restoration story it's very hard to create the political or religious transformation. It’s the absolutely fundamental, necessary but insufficient condition — because of course there are other things you need to do as well. But it is a necessary condition of transforming or mutating from one dispensation to another: you need to tell the story.

In the blaze of signals, so hard to decide. [o]

4. THE NEED FOR A NEW STORY

That led me to the fourth observation, which is that the reason we are stuck now with neoliberalism is that we have failed to tell a new restoration story. After the Great Depression, John Maynard Keynes sat down, wrote his general theory and told, very effectively and with brilliant panache, a new restoration story which was completely different from the prevailing ethic that he was contesting. Well, during the Keynesian era, the neoliberals quite consciously and deliberately set out to write a story of their own, and over the course of 30 years they polished it and polished it and they were ready, they were waiting. As Milton Friedman said with great prescience: Within about 30 years, Keynesianism is going to run into major trouble; we're going to bide our time; when the time is right, we will step forward and have it ready-made and just be able to hand it over. And this is exactly what they did: in the late 1970s, they stepped forward and said, “Okay, that old model has failed. Here’s a new one, on a plate. Oh, thanks very much, guv, there’s another story.” And it was just taken up, adopted during the Keynesian crises of the 1970s.

In 2008, neoliberalism implodes, completely collapses: the story that the markets can regulate themselves, that the less governments interfere the better it'll be for everyone, that wealth will trickle down from the rich to the poor. That whole thing was fundamentally disproved. Even Alan Greenspan, one of the most determined neoliberal advocates of all, was forced to admit there was a flaw.

And so, at this crucial inflection point, the opponents of neoliberalism stepped forward with nothing, absolutely nothing — no new restoration story at all. They hadn't even recognized that there was a need for one. All that people proposed was either: can we have a slightly less virulent neoliberalism, please?; or, why don't we go back to Keynesianism? Well, one of the problems with politics is that you can't go back, it's very difficult — unless you're a fascist; for some reason fascists are able to go back. But, by and large, it's very hard to revive and disinter an idea which has already had its sort of span of life, 30 or 40 years’ lifespan which is about the longest any story will last in politics. It's very hard to go back, partly because we like to distance ourselves from our parents’ generation a little bit, but also perhaps, primarily, because one of two things is likely to happen during the first lifespan of that politics: either its internal contradictions will emerge and it basically implodes as neoliberalism did, or its opponents will find very effective means over the years of destroying it, which is what happened to Keynesianism. With Keynesianism you have to have capital controls, you have to have fixed foreign exchange rates, you have to have a balanced global trading system to make it work; Keynes was highly aware of this. Well, a balanced global trading system never got off the ground. At Bretton Woods he tried and tried to push for the International Clearing Union, but it was scotched by the Americans, and the capital controls and fixed foreign exchange rates were torn down, starting in the 1950s, actually.

The idea that we could ever go back to that, and that the opponents of it might have forgotten how they destroyed it the first time around is, I think, stretching the bounds of probability; or, the idea that we can operate without those essential prerequisites. Well, we've seen what's happened. In 2008, the government introduced scrappage fees and scrappage payments, so you could trade in your old car and be given £2000 towards the cost of a new car, which was meant to be a classic Keynesian stimulus measure to get the economy working again. The idea being that people buy new cars so people are going to be employed manufacturing those cars and, therefore, they're going to spend more money into the economy. Yes, it worked very well in Germany and Japan because only 15 percent of the cars that we buy are manufactured or even assembled in this country, and so this was a lovely foreign aid package that we gave to Germany and Japan — because without capital controls, you can't keep it inside your own country. With EU state aid rules and rest of it, you couldn't discriminate between them. So globalization of capital has made Keynesianism effectively impossible.

The most political decision you make is where you direct people's eyes. In other words, what you show people, day in and day out, is political... And the most politically indoctrinating thing you can do to a human being is to show him, every day, that there can be no change. — Wim Wenders

But there's a third reason why Keynesianism cannot or should not be disinterred, and that, at its heart, is the notion of stimulus spending or deficit spending, the purpose of it being to sustain a steady rate of economic growth. Now, sustaining a steady rate of economic growth would be fine and dandy. There'd be no problem with it at all if the planet were also growing at the same rate. But sadly the planet is not. And so perpetual economic growth on a finite planet leads inevitably to the bursting of planetary boundaries and that's what we're seeing right now. The environmental crises I'm talking about are crises driven by economic activity pushing through the ecological boundaries that enable a safe space for humanity to inhabit, and this is happening with current levels of economic activity. Now, the IMF and the World Bank and people say, “Oh, we're not trying to be unreasonable. All we want is a steady 3% global growth rate,” which means a doubling every 24 years. So we double in 24 years from now, then we quadruple in a further 24 years, it's eight times in a further 24 years and sixteen times in the next 24 years! Which planets are we going to harness to support that growth? How on earth can it be sustained when we can't even support current levels of economic activity? It very soon becomes apparent that an inherently growth based system like Keynesianism simply cannot deliver the safe and just world in which we want to live.

NEW IDEAS IN DEMOCRATIC POWER

So we need a new story, a new restoration story, a story that tells us how we got here, where we now stand, what the future holds, and what it's going to be like when we get there. A story that lights a path to a better world, a story based on fact because there's no point in basing it on fairytales, as I believe the neoliberals have done. This sounds like a tall order, but I believe such a story is waiting to be told, and it goes something like this: the land has been thrown into disorder by the powerful and nefarious forces of neoliberal politicians, economists and journalists who have torn society apart, who have atomized and ruled, who have told us that there is no such thing as society, that our role is a noble role of fighting like stray dogs over a dustbin, that our lives should be defined by competition and extreme individualism. In doing so, they have damaged human society, damaged the living planet, undermined the basis of common wealth and common decency. But we, the heroes of this story, will fight back against these powerful and nefarious forces by rebuilding community, by creating what I call a politics of belonging: generous inclusive communities, but also communities built with a geographical basis, not just online communities, not just broad communities of interest (those too, yes); but, primarily, communities where you have a sense of geographical belonging. Not exclusive belonging — not “us kind of people with four generations in the churchyard belong there and new incomers don’t” — but a place where anyone can belong, even if they're just there for six months. And in that revitalized community we see the stirrings of new democratic power and new economic power arising from people no longer controlled by the elite. And in doing so, we restore order to the land.

This might take some unpacking. Because we have merely an hour — and I am not quite up to a Fidel Castro-style speech this evening — I'm going to do so by way of picking out one or two examples to give you an idea of the sort of thing I mean.

Planting 5000 trees in Sheffield. [o]

A key task we face is to rebuild genuine, thriving, vibrant communities. This is partly because it is essential for our mental health that the extreme alienation that we suffer on so many levels converges into psychic rupture, which a lot of people are now suffering from, and partly because if we don't get there first, the fascists will. Hannah Arendt pointed out that fascism arises from atomized societies, and it is in the dust and powder of a shattered society, where people have no sense of belonging, that they find that sense of belonging in fascism. That is because fascism, at heart, is offering a community, a very tight community where you wear the same uniforms and you march to the same music and you stamp on the same heads. It tells you that you, the insider community, are the dominant virtuous people, and everyone else is to be crushed and destroyed because they have no virtue. What draws people in is this sense that you are literally marching together. Unless you create a generous and inclusive community, the alternative is not no community, because we can't stand that; we’re so socially minded that we cannot live without community. The alternative is an ugly, exclusive, and cruel community. So it's an urgent necessity to start rebuilding communities that work, and the reason why they should, at least in part, be geographically based — actual communities attached to place — is that this gives people the fundamental sense of belonging, which is absolutely key to our wellbeing, and key to determining what it is that we fight for.

Look at the people of Sheffield: they are, hundreds and hundreds of them, now fighting for their trees. They're not fighting for the trees somewhere else in Britain, they’re fighting for the trees in Sheffield. They feel a sense of belonging to, with, and in those trees, and the city that the trees represent to them. They will put their liberty on the line in order to defend those trees because they have that investment in their geographical community. It's very easy for us as sort of internationalists, as people with a wide cosmopolitan view to say, “Well, we shouldn't just focus on one place, we should be looking at the plight of everyone,” which is absolutely true. But that doesn't mean you don't also focus on the one place. So, “think globally, act locally”, I believe, turns out to be an absolutely fundamental, important and true message.

So how do you revitalize communities in a situation of atomization, and also a situation of a very rapid turnover, with people coming in and moving out? So many people I've met around the country, they're pitched up somewhere, they're only going to be there for a few months, they don't get to know anyone and they start to feel very lonely. What I want is to live in a country where everyone has a sense of belonging, however short their stay may be, because they can immediately plug into community activities, community groups, plug into a sense of community — even if they're not going to be there for very long.

There's now almost a science of how to make this work, summarized in this wonderful 400-page report produced by Lambeth Borough Council in London. It looks around the world at what has worked and what has not worked, and what they find is that to create what they call a participatory culture you need to have a mixture of activities, some of which are very complex and sort of involved, but, a lot of which are what they call low threshold, low commitment activities: things that anyone, regardless of their socioeconomic status, can dip into or dip out of without any sense of threat, without any sense of long-term obligation, without any sense of having to have a particular skill set or particular connections to do that.

The classic one is eating together. Anyone here know the etymology of the word companion? Companis: “with bread”. This is a fundamental aspect of our humanity, eating together. Sitting in front of a TV with a microwave meal that you're stuffing into your face doesn't count, and really, we have to reclaim that lost art. It's not difficult, and of course there are wonderful projects like the one set up by the Eden Project called the Big Lunch: 18 million people in Britain participated in it last year where, for a day in June you put either tables down the street, or you use a large space if it's raining, and everyone brings their food. You might bring some music to play and various other things, but you eat together and you get to know your neighbors that way — a really fundamental thing. But there's also their shared childcare, their shared boat-buying, their shared making and mending stuff, a lot of things which you can dip into and dip out of — these are very important. Yet, you need some anchors as well, you need some focal points.

PARTICIPATORY ECONOMIES

A classic example they point to is something that happened in Rotterdam in 2011. Rotterdam is a big post-industrial dock city with a lot of problems, a lot of divided communities, a lot of balkanization. Along come these sort of anarcho-punk types who set up a little festival, in a disused Turkish bathhouse, and they called it The Reading Room. They put on plays and films and gigs, and there was a bar, a cafe, hangout spaces, and it became wildly popular! People persuaded them to keep it running after the week that this festival was supposed to run for, and so they turned it into a permanent fixture. Then someone said, “Well, yeah, but if we're doing this, we need to crash.” “Oh, right, someone better set up a crash.” “What about the old people who can't get out of their homes to come here?” “Oh, yeah, someone better set up an outreach service for them.” What about this, what about that? All these things started proliferating, started budding off the initial idea. It helped to spawn 1300 projects, quite extraordinary, and it has transformed the face of Rotterdam. Today the council makes no decision without consulting the community groups, because it says, “Yeah, you guys know how to do this much better than we do, you've sorted it out, you've worked it out.” That is creating a participatory culture — what the study calls a thick network. Once you've reached 10 to 15% penetration, 10 to 15% of people engaging in community projects, you get this sudden takeoff and it becomes the norm to engage, it becomes a bit odd not to be involved in the community project. Then you have this real sense, like in Rotterdam, of everything just coming together and transforming the city. And, you can take this further — through various forms of participatory democracy and participatory economy — to give people even more of a sense that their city or county belongs to them.

50,000 people a year take part in a local budgetary process... [o]

In Iceland now, in Reykjavik, the capital, something like 60% of the population of the capital has taken part in this participatory democracy exercise, whereby anyone could submit an idea for the improvement of the city. Everyone else in the city then votes on the idea and the most popular ones get put forward to the council and the council has to make a very rapid decision as to whether it's going to adopt it or reject it, with very good reasons. This has turned the city around and, again, it's been utterly transformative. There is now this very strong sense that the city belongs to the people, not to the politicians.

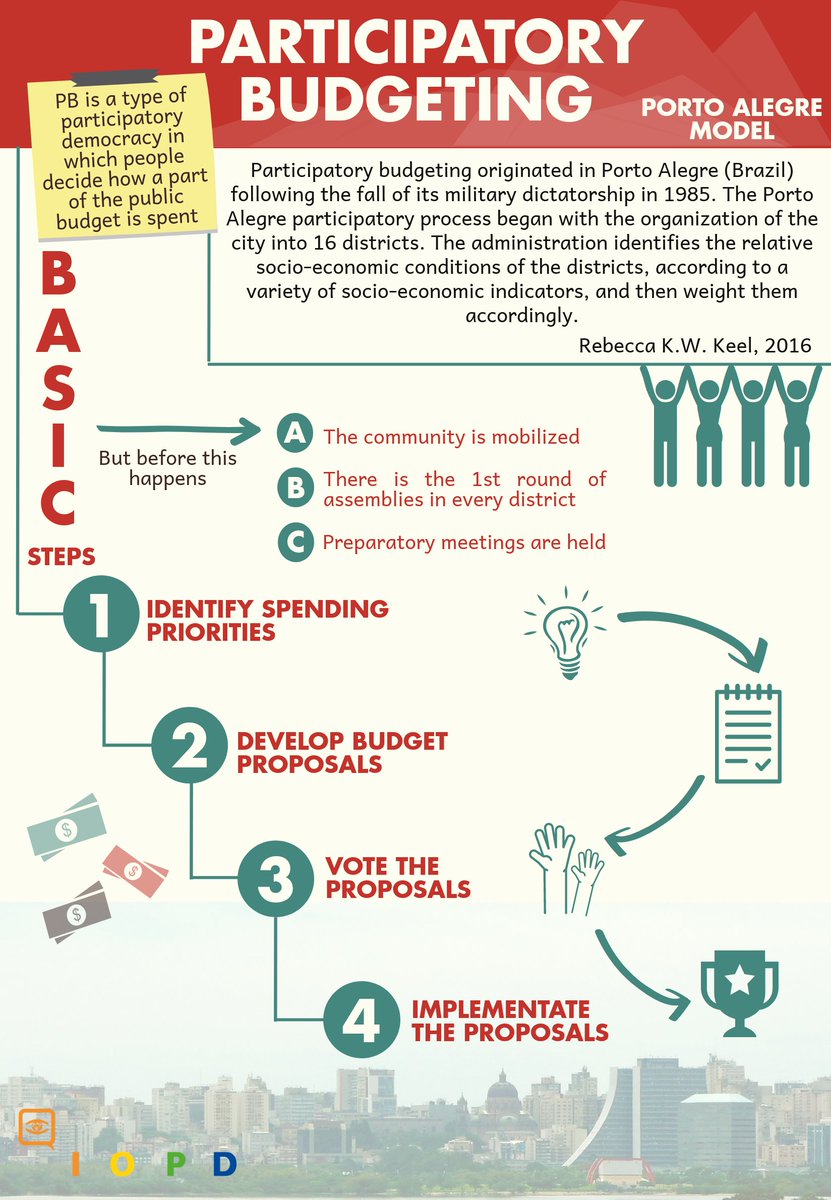

Even further down this line is something that started in Porto Alegre, in the south of Brazil, and has now spread to several hundred cities around the world: participatory budgeting. Instead of you handing over your tax money or your council tax, and the council says, “Right, we're going to spend this on that and this on that, and what-have-you,” and it all becomes a bit opaque, you don't really know what's going on, and you don't really know if the right decisions are being made. Instead of that, participatory budgeting has the whole city setting the budget. They have these masses of converging district meetings. In practice, 50,000 people a year take part in the budgetary process, and the results have been spectacular.

If you compare Porto Alegre to similar cities in Brazil which do not use participatory budgeting, Porto Alegre now has far better sanitation, far better water quality, many more nursery places, much better primary healthcare, much better education — it goes on and on. This sort of takeover by the people of the infrastructure budget has transformed the city. And, the mafia has completely disappeared because what gives mafia their strength and staying power is that they provide services that a corrupt and useless council is not providing. Participatory budgeting has wiped out corruption and it has produced something which political scientists will tell you is completely impossible: people lobbying for their taxes to be raised because they can see the point of public spending when they're in control.

RECLAIMING THE COMMONS

But even this, I feel, could go still further. And the stage I would like to move that thinking onto is the reclamation of the commons. How many people here would be comfortable defining the commons? Very good: one. One is about average. So thank you for that. Don't do yourselves in: one is perfectly normal in an audience of this size. It is amazing that the commons is one of the four basic pillars of the economy, but it's been so excluded from economics textbooks and from general discourse that we don't even talk about it anymore. But not long ago — about three hundred years ago — most property, most assets, most resources, were held in common. When we talk about politics and we place ourselves on the political spectrum, we do so along a single axis: with the state at one end and the market on the other. If you're on the left, you say you want more state and less market. If you're on the right, you say you want more market and less state. But there are four primary pillars to the economy, and one of them is the household or core economy, as some people call it, and the perennial neglect of the household is absolutely fundamental to the functioning of the rest of the economy. If children are not fed, watered, loved, taken to school and all the rest of it, they cannot become functional adults, they can't participate in any other form of economic activity. And because we neglected this, we neglected the crucial economic role of women who are still the primary carers at the household level.

In a wonderful book by Katrine Marcal called, Who Cooked Adam Smith's Dinner, it turns out while the great man was writing The Wealth of Nations, his mother was scurrying around making his dinner, cleaning his clothes, making his bed and all the rest of it and he completely ignores this massive economic contribution which made the writing of The Wealth of Nations possible. The hands of his mother remained invisible. Marcal points out that he simply could not have written that book, and no one he was writing about in all these sort of macho activities involving hammers and water wheels, or whatever could have happened if there wasn't a household behind them. That's number three pillar of the economy and number four is the commons.

What is the commons? A commons really consists of three elements. (This is my sort of condensed definition, you could probably give a better one). The first elements is a resource, a particular resource, a piece of land or the water flowing off a hillside; it might be a forest, a fishery, or it might be some software or an academic journal, but it is a particular resource. The second element is that it is controlled by a particular community that has possession of it, yet not necessarily property ownership of the kind that we recognize today. The third element is the rules and negotiations which the community produces in order to manage the resource. Any product from that resource is shared on an equitable basis amongst the members of this community.

THE ENCLOSURE MOVEMENT: BEFORE AND AFTER. [o]

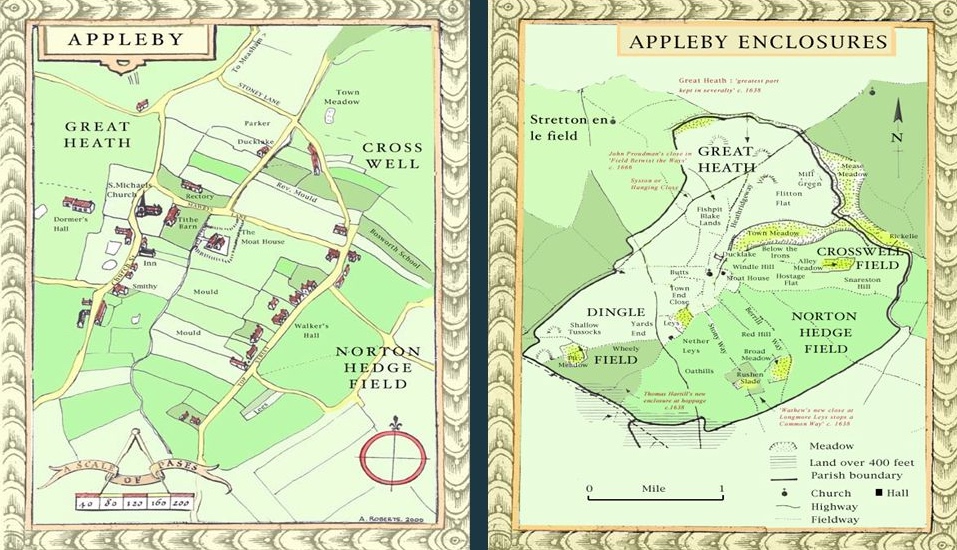

Now, as I suggest, you go back a few hundred years and this was the dominant model for land; almost all land, the fundamental resource, was held in common, and this was the case worldwide. The notion of private individual property was as crazy as the notion of owning a piece of air, it did not figure in people's minds. It wasn't something which people even would have thought of as a thing, let alone as a legitimate thing.

The change began in England, as it happens, in the 16th century, primarily following the dissolution of the monasteries, and people began acquiring private land ownership. This had its upside in that with that came the notion of individual rights which began to cede the notion of democratic rights and led eventually to the massive contest between the landowners and the crown which culminated in the English Civil War. Following the English Civil War, they began grabbing more and more land because the crown had been pushed back and there was no real constraint in their ability to do so, and we saw the massive process of enclosure that transformed the face of Britain, as a small group of people grabbed what belonged to everybody. And while it helped to sow the seeds for parliamentary democracy, it also destroyed economic democracy, or the prospects for economic democracy, which in turn then undermined parliamentary democracy as we're now seeing with this tremendous power of the enclosure class, which we also call the 1%.

Now, when I worked abroad, particularly in West Papua, and Brazil, and East Africa, I saw with my own eyes these enclosures taking place: people being deprived of their ancestral lands, a few people grabbing that land, throwing the previous inhabitants off their land, who would then spiral into despair and dissolution, alienation, anomie, alcoholism, drug addiction, all those social ills basically followed from losing, not just your livelihood but your sense of belonging, your sense of place, your community, and all the ceremonial and spiritual life invested in that community as well. The whole lot gets pulled from under you and you are left with nothing except your fragmented, shattered mind. We can't form a mind by ourselves, we have to form our minds with other people. We are this supremely social mammal with the possible exception of the naked mole-rat, but we won't go into that now.

JOHN CLARE"S LIFE OF REFLECTING THE LOCAL

It was only a few years after coming back to Britain that I started reading the poems of John Clare, possibly, I think, our greatest English poet, this peasant self-educated poet. In his early adulthood, his youth and early adulthood, he describes this with great beauty: the nature that surrounds him, but also the community life and activities around the year that people engage in: economic activities, ceremonial activities, community activities, and the fact that they weren't really separated. They were all mixed into one and you were constantly engaging in community life in whatever you did. It's a very rich and beautiful portrait he paints of what was going on in his parish. Then, in mid-adulthood, everything changes. He starts writing poems like ‘The Fallen Elm', and ‘The Mores,’ and ‘The Lament of Swordy Well’, which described this complete shattering of that world as the enclosures come in, sweep everybody off the land, sweep the features off the land, cut down the trees, destroy the habitats, drain the marshes, put up fences, put up ‘No Trespassing’ signs, and put their sheep in where the people were. And what happens to John Clare? He becomes an alcoholic, he loses his mind, he dies in a lunatic asylum. It suddenly struck me that what happened to all of us — regardless of where our ancestors came from in the world, because this model which started in England was spread to Ireland and then to Scotland, to the British colonies, and spread from the British colonies into the rest of the world. It has happened to everyone, and we wonder why we are so troubled. We wonder why we have such high rates of alcoholism, drug addiction and all the other social pathologies that we contest with. We lost the commons, and in losing the commons, we lost ourselves.

You ask for one hour of envelopes stuffing, no one turns up. “Well, okay, I want you to run the campaign.” “Yeah, yeah, we'll run the campaign.”

So how do we reclaim the commons? I'll give you an example of how it could be done, and what I'm going to talk about is something which I think is very close to the economic, social and political lives of everyone, and that is urban land. When I say urban land, I bet you start thinking about open spaces, parks and stuff like that, because that's what we think about when we say land, isn't it? Yet, most urban land is under buildings and is what gives those buildings their value. Not bricks and mortar which makes houses so expensive, but the speculative value of the land on which they sit, a value which the owners of this land do not create. It’s created by the infrastructure provided by government, it's created by the economic activities of other people, setting up their businesses and the rest of it, all of which makes their location desirable and raises the value of that land which is then pocketed by the person who happens to own it. When you're looking at these very rich property owners owning big chunks of urban land, they're making millions and millions every year from our economic activities, and they sit there and harvest it. They fill their pockets with other people's work, in effect. And so the answer to this, I believe, is land value taxation, highly progressive and structured to aim primarily at the richest and biggest landowners in the cities. Land value taxation makes a great deal of sense in an age of great wealth inequality, when that wealth is vested to a very large extent in land. It's got the further advantage that you can't move your land to Panama, and it has the further advantage that it generates a lot of money potentially; and, part of this money should be used by the state to fund public services and the rest of it, as per. But the residue should be divided up and passed back to communities, and communities would be encouraged to set up a trust to take that money. They would also be given various other elements of political help such as, for instance, the community right to buy, of the kind they already have in Scotland, and possibly also a community right to land assembly.

With this money you're allowed to use it to buy land. So what are you going to do? You set yourself up as a community group in part of the borough, and you look around to see what comes up for sale. Well, this casino has come up for sale. Do we need a casino? Is that the thing we need more than anything else? No, good. Let's buy it. So you buy the casino and you knock it down and you say, right, what do we need here? Oh, yes, that thing called affordable housing. I don't mean affordable housing, I mean affordable housing. Let's build an estate with a large element of affordable housing. And we don't want it to become a ghetto, we want it to be a mixed development, but we want the majority of the houses to be genuinely affordable and a lot of them to be up for social rent. But we're not going to build this estate ourselves. We're going to go to people at the top of the social housing list, and people who are would-be owner-occupiers and want to put down a deposit, and say to them, “You've got this option of putting your names down as the future occupants of the estate, and you are going to design the estate. We'll give you some professional help. We will give you expertise on tap for when you want it, but it's you who are going to sit down together and work out what this is going to look. You can design your own homes, but more than that, you are going to design the whole estate.” And what we see all around the world is that on those rare occasions when people are allowed to design their own estates, they are a hundred times better than when you get some volume house builder helicoptering down their standard design again and again on a take-it-or-leave-it basis, which means the take-it basis because they got no sodding choice.

And people do things like designing children in, so children have got somewhere to play. That's a novel idea. Or having houses which face each other, so there's a friendly atmosphere so people come out their doors and might meet each other rather than just scurry into their cars and drive away. When you tap into people's collective genius, all sorts of design elements come to the fore. Obviously you can learn from stuff which has gone before, and tap into the expertise as well, but you see this massively improved design. And in doing so, you do something else. By the time those people move onto the land, they've already formed a community, they've been working together for two years and probably hate each other, but they all know each other very well and they’ll be forced to work constructively. They have to get on with each other.

Now you have this ready-made community. And what a transformative impact that has, rather than just filling up some developer’s estate with whoever comes, whoever can afford to buy the houses. You've got this estate which is generating social rents, coming back to the commons’ trust, which is now a commons land trust that you've set up, and you're still receiving residue from land value tax coming into your coffers as well. What do you do next? Maybe buy more land, build more houses. Maybe if that's the primary thing, then keep doing that for a while. Since your money is still accumulating, you might want to set up some amenities, a youth center, a library center, a children's center, some things which had been disappearing, or you might want to issue a local basic income to the people in your community with that money — because there's a commons, shared in equal basis, the product of your resources.

A graphic illustrating action and education possibilities on the website of Participatory City, an initiative in Barking and Dagenham, UK. [o]

So you begin to see how, through a series of measures, you can have this potentially transformative effect within a community, and transfer both power and money back to the people and away from the illegal. Of course for this to happen you need a supportive and enabling state, and almost nowhere on earth at the moment is there a state which is in a position to start doing that. So we need regime change, democratically, of course, and peacefully.

THE VOLUNTEERS JUST TAKE IT

There are some very exciting new ways of achieving this, and I harken back in particular to the amazing thing that happened in the first half of 2016. You're scratching your heads, “What possible amazing thing happened in the first half of 2016 – haven't the past three years just been a total disaster?” Yes and no. What I'm thinking of is the Bernie Sanders campaign, and you say, “Well, now he's completely lost it — the guy not only didn't get — let alone the presidency — he didn’t get the Democratic nomination. Surely that was a failure.” Yet something very interesting happened in the Bernie Sanders campaign. You can see it as a gigantic live experiment in which they got an answer to their experiment, but only in the last four weeks of the campaign. The people running it were so frustrated, saying, if we had two more weeks, we would have got there. Anyway, it's incredible what happened, because you start with this guy who had 3% name recognition, who was universally dismissed by the media as a total superannuated no-hoper and, rather importantly, in a US presidential race, had no money. But so he sat down with his two or three staffers that he could afford to employ and said, well, what are we going to do, what have we got? And they said, “The only thing we've got is the enthusiasm of the people who want you to be President.” And so some bright spark, he said, “All right, let's start using those people, let's try farming out some of the jobs which would normally be reserved for staffers, paid staff members, to volunteers. “Oh that's a bit scary. They're bound to screw it up.” Well, they gave these volunteers something small to begin with and they mopped that up. “Okay, we'll give them something a bit bigger.” "Whoa, they bit my hand off!" The volunteers just take it, whatever you give them. The campaign discovered that the more you ask people to do, the more people come forward to do it. It's so paradoxical. You think, “Oh, I can't ask too much of them.” You ask for one hour of envelopes stuffing, no one turns up. “Well, okay, I want you to run the campaign.” “Yeah, yeah, we'll run the campaign.” Thousands of people started flocking in, and seeing that they had meaningful and useful tasks to do, the tasks which staffers would normally do, it began to roll, it began to proliferate. And then someone had the bright idea, what if instead of training all these volunteers ourselves, we use the first wave of volunteers to train the second wave of volunteers. “Oh yeah, that works too.” And then the second wave trains the third wave, etc.

By the time the nomination process closed, they had recruited a 100,000 volunteers who themselves had run a 100,000 events and had spoken directly to 75 million Americans. They reckoned that with another three or four weeks, they would have spoken to every accessible adult in America. And not as a paid staffer with the clipboard saying, “What do you think about this?”, but as someone saying, “Yeah, where you are is where I am. The shit that you're suffering in your life is the same shit I'm suffering in my life,” which is so much more powerful than having some paid person turn up. What you saw with the Sanders process is it started off like this and it started to rise and it spiked up and then the deadline, the cutoff came. It was at that point that he was going to overwhelm Clinton — with two more weeks she wouldn't have stood a chance. And then I believe Trump wouldn't have stood a chance either because with that rolling momentum which the Sanders campaign had developed by creating a political community, a politics of belonging within politics, this proliferating community he had tapped into became something immensely powerful.

“Yeah, where you are is where I am. The shit that you're suffering in your life is the same shit I'm suffering in my life.” [o]

So I read a book called Rules for Revolutionaries by Becky Bond and Zack Exley [see excerpt of this book in these pages], it's full of amazing stuff. And very soon after reading that, Theresa May called the election in Britain. If you remember the great debate at the time was, “Are the Conservatives going to get a majority of 100 or 120?” That was about the only debate there was. But I just read this book and I thought, well, why couldn't Labor do this over here. And maybe they would stand a chance if they did. So I made a video for the Guardian saying this. And there's a good rule in journalism: never read the comments below the line. But I have this fatal attraction, I can't stop myself from seeing, in this case, what people wrote. It was like, "Oh god, oh no, why did I talk about wishful thinking?" There was not a single positive comment. Every single one was, "Right, he's completely gone off now. Labor standing a chance in this election? That's utterly ridiculous!" Well, little did I know — and this had nothing to do with me — as I was making that video, Corbin was talking to some Sanders’ organizers who he had brought over to Britain, and they used the big organizing technique to galvanize the labor grassroots and momentum by doing a very similar thing to what the Sanders organizers had done in just six weeks. Well, you saw the result, the biggest political surprise in British Democratic history, an extraordinary thing. They thought this resurgent prime minister was going to sweep in with a crushing majority and she'd be able to do whatever she wanted and would be strong and stable in the national interest forevermore. Well, we saw what happened.

It's my contention, ladies and gentlemen, that if we can pull together that big organizing model — as they call it, the Sanders model — with a powerful new restoration story, we bring those two elements together and we become unstoppable.

Thank you. ō

WATCH the video of this lecture.

GEORGE MONBIOT (MON-bee-oh) is a British writer known for his environmental and political activism. He writes a weekly column for The Guardian, and is the author of a number of books, including Captive State: The Corporate Takeover of Britain (2000), Feral: Searching for Enchantment on the Frontiers of Rewilding (2013) and Out of the Wreckage: A New Politics in the Age of Crisis (2017). He is the founder of The Land is Ours, a campaign for the right of access to the countryside and its resources in the United Kingdom. His "political awakening" was prompted by reading Bettina Ehrlich's book, Paolo and Panetto, while at his prep school.

Comments

Thank you; and thank you,…

Thank you; and thank you, too, whoever transcribed this.

Monbiot - brilliant, inspired and inspiring as ever. One of the few lights in our current darkness.

Good article, George. I had…

Good article, George. I had given you up as a hopeless liberal. Your solution here goes part of the way, but as for "we need regime change, democratically, of course, and peacefully."

We need regime change all right, but that means depriving the rich and privileged of their riches and privileges, which are the root of the whole problem. They will not give these things up voluntarily, no matter what votes you win. It has never happened in the history of the world. If we want change it must be taken by force, just as at present these privileges are held by force. That does not necessarily mean violence though. A general strike, with means to support the strike is a better answer. The present unrest in the US could be a starting point, if they can persevere.

Add new comment