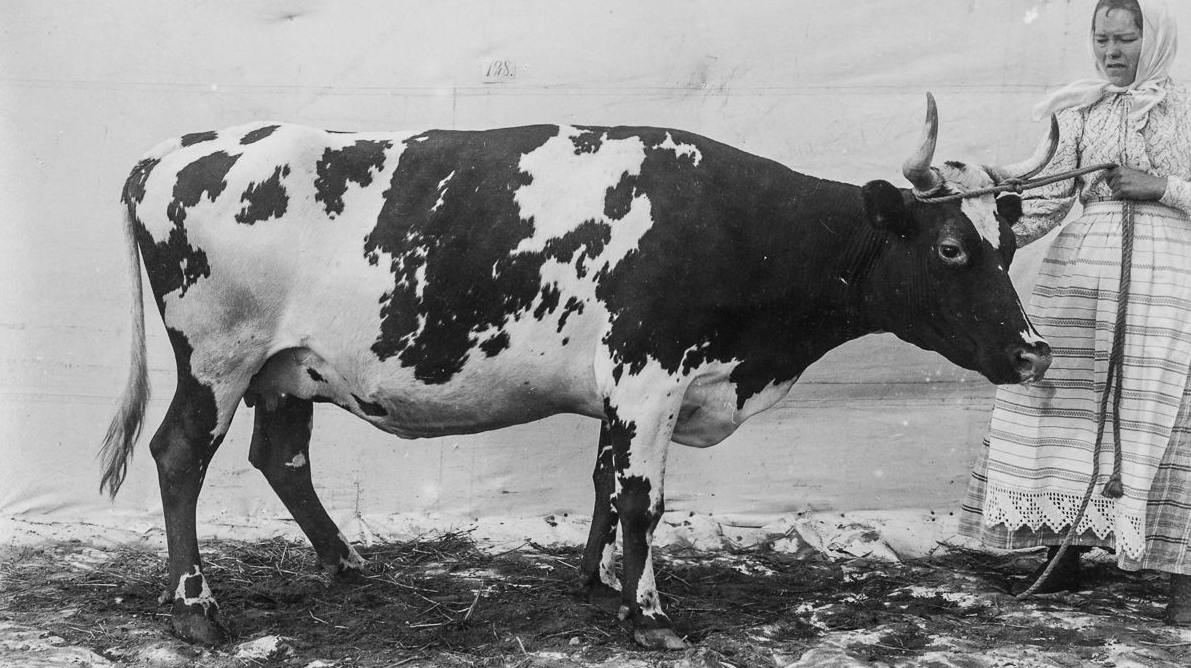

From Finnish cow portraits, 1899. [o]

VIEWPOINT

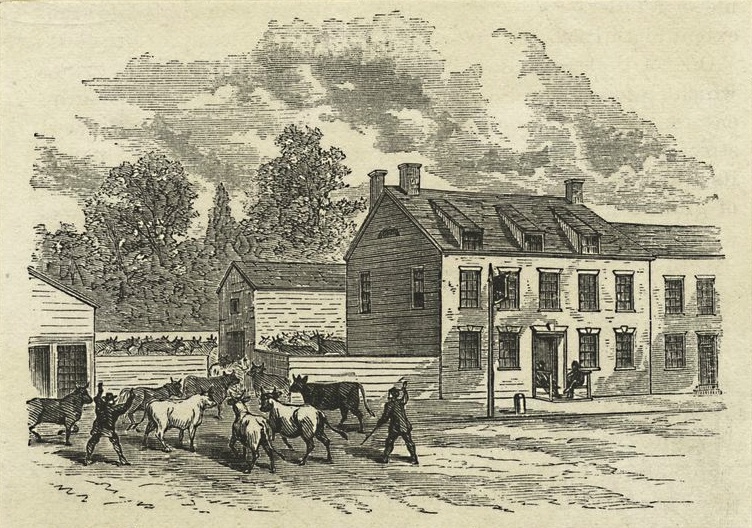

The farmer’s boy

had ridden ahead on his bike

to warn us.

Turning off the ignition

we waited in the narrow

boreen, windows up.

And suddenly they came at speed,

a great bull in amongst them,

the dog snapping at their hooves,

their near-panic as they saw

the car and divided either side —

squeezing between us and the walls,

shoulders the height of our roof,

their sheer weight and bulk

jostling, sweeping by

like a tsunami wave.

After they’d passed

we breathed again —

no damage done

except for one forlorn

wing mirror, dangling

by its tendons.

Great Blue Heron. [o]

SWAN, HERON, DUCKS

The surface on the canal tonight: black cellophane.

And music without volume — here in overlapping

rhythmic channels of water birds. On her island nest

a white goddess folds an angular neck, arranging

and tuning feathers; then like a great winged

accordion at the heart of this session, flamboyant

flapping brings wind and sound to the picture.

Across the weir, her partner raps with an old heron —

bird banter between tunes, before the frey one swoops

above the reeds towards a suitable platform for business;

no show, motionless now on spindly fiddle-bow legs —

content to sit this one out, waiting perhaps for a call

to sing an old heron song — and all this time, weaving

in their own patterns, the coming and going of ducks,

silver-grey in the moonlight, tracking their own

invisible melody, dipping and diving…

Cows being herded. [o]

REQUIEM

The cows have gathered in an adjacent field,

I can see their shapes in the moonlight —

a meeting of the tribes, they are here in their multiplicity;

black, brown, black and white — some all white,

like ghosts, or recent converts.

Just now I heard a moan from one of them

that had me awake as if I had been shot.

It’s the night before their calves are taken,

they know from the look in the farmer’s eyes.

They call him by name

although it sounds like ‘moo’ to us.

I listen at the window to their keening —

we make recordings of whales and dolphins,

say they are a higher species

as close to us as nature gets —

but the cows are singing in their camp,

refusing to be cattle

marking their loss

celebrating the grass

thanking the rain.

The females, even the males most of the time

are gentle, considerate, abiding.

But tonight the cows have run out of patience,

can ruminate no longer; they sing

their mass; make ready for battle,

tomorrow they will paint themselves red —

attack.

Peter Mullineaux fills out

THE WILD CULTURE SCRIBBLER'S QUESTIONNAIRE

1 What is your first memory and what does it tell you about your life at that time and your life at this time?

My earliest memory is of a weir in Tewksbury which ran by a cottage we lived in when I was about 2 years old. I had thought this was just a dream, but many years later, as an adult, I happened to visit the town and saw the exact place just as I remembered it.

2 Can you name a handful of artists in your field, or other fields, who have influenced you — who come to mind immediately?

Songwriters: Bob Dylan, Neil Young; Leadbelly and other blues artists. So many poets! Seamus Heaney, Mary Oliver, Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Frost, Wordsworth, Benjamin Zephaniah.

3 Where did you grow up, and did that place and your experience of it help form your sense about place and the environment in general?

I grew up in Bristol, UK. We lived in Henbury at the north edge of the city, our garden backed onto some amazing woods. I spent much of my childhood in there amongst the trees. We also went to the seaside a lot and the seashore is a big pull for me still. Here in Galway we’re blessed with some fantastic coast.

4 If you were going away on a very long journey and you could only take four books — one art book, one fiction or poetry, one non-fiction, one theory or criticism — what would they be?

An art book on Dutch painters; Robert Frost’s Collected Poems; non-fiction: Sapiens by Harari; and The Ancestor’s Tale by Richard Dawkins.

5 What was your most keen interest between the ages of 10 and 12?

Greek mythology.

6 At what point did you discover your ability with your writing?

I was fortunate in getting my poem ‘Harvest Festival’ published aged 13 in an anthology Poetry & Song (Macmillan). It was then published in Man & His Senses and recorded on Argo Records alongside music by Ewan McColl and Peggy Seeger.

7 Do you have an ‘engine’ that drives your artistic practice, and if so, can you comment on it?

Love of nature; the presence music in nature and human interaction. All issues around social justice; empathy with other species and the future of our planet.

8 If you were to meet a person who seriously wants to do work in your field — someone who admires and resonates with the type of work you do, and they clearly have real talent — and they asked you for some general advice, what would that be?

Trust your instincts; be prepared to plough a lonely furrow sometimes. Remember there is pleasure and fun as well as camaraderie in exploring serious themes and issues.

9 Do you have a current question or preoccupation that you could share with us?

My writing (poems/plays/songs/and a first novel coming along) connects to my work in development education, looking at global issues. I work with Poetry Ireland’s Development Education through Literature Project (in schools) and on the ‘Just a Second!’ project with Afri (Action from Ireland) which focuses on the human, environmental and financial cost of our staggering amount of spending on the military and conflict, in fact our obsession with violence overall.

10 What does the term ‘wild culture’ mean to you?

Freedom from damaging manipulation by human beings.

11 If you would like to ask yourself a final question, what would it be?

Are there any other ways I can use my voice to make things better?

PETE MULLINEAUX has had four poetry collections published, most recently How to Bake a Planet (Salmon Poetry 2016), and a number of plays produced on RTE radio [the principal radio channel of Irish public-service broadcaster Raidió Teilifís Éireann]. He lives in Galway, Ireland.

Add new comment