I go out to pick kale for dinner to find it has already been munched. Large bites have been taken out of most of the tops. Some still have wet salvia on them, glistening in the evening light.

Deer.

There had always been deer making occasional forays into our market garden: roe deer are plentiful in this corner of southwest England. One or two would appear like ghosts at the far end of the field on spring evenings, take a few nibbles of tender young leaves from the nearest trees, and scoot at the slightest sign of human activity. But recently they’ve become increasingly bold, coming further and further in, helping themselves to lettuces, beetroot tops, flower seedlings, anything that takes their fancy.

One morning I found a young one in the polytunnel, a walk-in plastic tunnel we use for growing. I scared it good and proper, banging on the plastic and shouting. It panicked and ran from side to side of the tunnel, terrified and confused, until it found its way out the back and bounced away across the field. That one won’t come back, I thought. But it did.

In theory, everyone was on board, even the one vegetarian among us — provided she wasn’t around when it happened.

They come right down to the house, eating the new grass on the lawn. We’d open the door and shout and wave at them and they’d run for a few yards up the field, then turn around and stare at us like defiant teenagers.

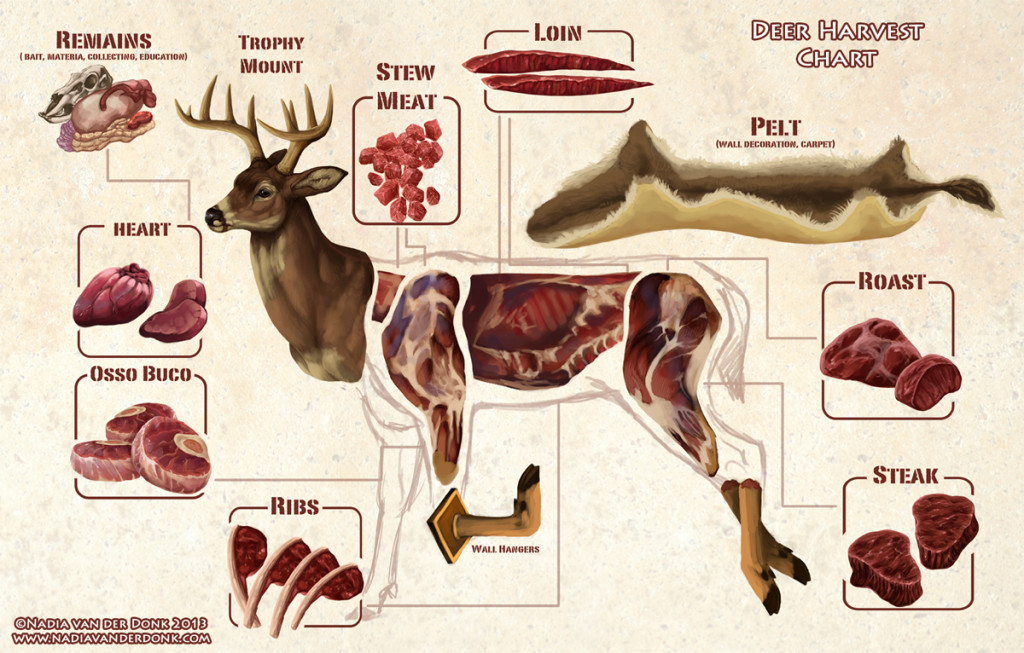

Pete had found a dead deer once, down by the gate into the bottom field. It was still warm, recently killed, probably brought down by someone’s dog on the loose. Not wanting to waste it, he phoned a friend who knew about such things and together they carried it up to our then half-built house. Hauling the body up to hang upside down off one of the still-exposed beams, Larry showed us how to butcher it.

He started by making an incision into its throat to drain the blood, which spilled copiously, red-black and glistening — a sacrifice blessing our new house. I remember little about the rest of the process, except that with the skin peeled off the body it looked shockingly vulnerable, a newborn thing, half formed. Most of it ended up in Larry’s freezer, since we didn’t have one. Pete tanned the skin to use as a rug, stretching it out in the top of one of the polytunnels to dry. It hung there for weeks, like a giant brown bat in mid-flight.

'Maybe, in a wild world, it would stop us killing more than we needed to for food.' [o]

When the deer started causing so much trouble I thought, shouldn’t we just shoot them and eat them? It seemed the sensible thing to do, a way to turn a problem into a benefit: our own free-range, sustainable meat source.

The neighbour was having problems, too, with the deer eating her young trees. We discussed the issue many times. In theory, everyone was on board, even the one vegetarian among us — provided she wasn’t around when it happened. I thought a lot about buying my own gun and learning how to shoot, but I’d need a licence and more time and money than I had. I phoned someone who would have done the deed for us, as did our neighbour. Somehow we kept putting it off.

The need to control the deer became less acute as the market garden became less commercial, less controlled and managed — and more attractive to wildlife. I started to enjoy it, this letting go. Released from the tyranny of needing to earn a living from the land, I began to marvel at the soft delicacy of wild grasses in flower, to feel a small surge of excitement at the appearance of campion and stitchwort in our hedgerows, to catch my breath at the hovering of a kestrel above the field, or the mysterious call of a barn owl, right outside the back door. I felt an atavistic thrill in these things, some deep part of me answering their wild call.

The deer were a part of this untamed resurgence, and in the end I had to admit that the killing was never going to happen. Our hearts weren’t really in it, and no one, including me, could summon the will to see it through. Instead, we covered everything that could be eaten with white nylon mesh, and the field started to look like an outdoor version of Miss Havisham's house — ghostly, shrouded, neglected.

'He started by making an incision into its throat to drain the blood . . . a sacrifice blessing our new house.' [o]

There’s an inevitable gap between thought and action when it comes to killing an animal. Rational thought, logic, even ethics, can have us convinced that it’s the right thing to do. But actually doing it? That’s a different matter. Without the necessity of needing to kill to put food in our mouths, we become sentimental and squeamish. We are glad to let someone else do the killing for us: out of sight, out of mind, even though we know that we are deferring responsibility, and probably, unless we’re careful, buying into a system that abuses animals in a way we find abhorrent.

Maybe it’s a good thing, this sentimentality. Maybe it’s right and proper to feel for our fellow creatures — a sign of our humanity. Maybe, in a wild world, it would stop us killing more than we needed to for food. But in our modern world, I can’t help but feel that it disconnects us — from nature, from the physical, maybe even from all that is real.

I found myself sadly buying venison from the butcher, killed by someone else, all wrapped up in little plastic packets. I had no part in that deer’s death, had no way of knowing if it was a good death. I was just a consumer, and there was no link between me and the animal.

'But in our modern world, I can’t help but feel that it disconnects us . . .' [o]

A couple of weeks before we moved out, leaving the market garden for good, I came down to the living room in the morning to see a young deer nibbling the grass on the lawn, just outside the French doors. It could have been the same one that I had frightened in the polytunnel. It had that innocent, tender grace that only young deer have, the liquid eyes and overlarge ears, the spindly legs, the curve of a long neck, the oh-so-soft red brown of the pelt. A perfect mix of ungainly and elegant.

It was blissfully unaware of me. I sat and watched it for a long time as it browsed up to the verandah, then found my phone and took a video. Later, after I turned away to get on with my day, it was still there.

MANDY GODDARD is a market gardener turned writer. She is working on a book about our relationship to land. She lives in Devon, England.

Comments

I am sorry this ended

I am sorry this ended sentimentally. Many thoughts;

First of all, in the rural part of NYState that I know, deer are a scourge. In ascending order of importance, they are making it impossible to grow a garden; changing the ecology of the forest floor; causing Lyme disease, Ehrlichiosis, and babesiosis; and killing themselves and drivers on the road. A longer hunting season and being alllowed to take more deer would help both them and us, but the reality is that their natural predators are gone and there are now desperately too many of them.

Second, the kill-it vs. buy-it-shrinkwarpped thing. A deer killed cleanly by a hunter has lived a good life and a quick and humane death; a shrink-wrapped chicken more likely than not lived an awful life -- packed in with others; its beak clipped because anxiety means it would peck itself and others to death; no one caring whether it suffers in life or in death.

Those in the US who prevent more deer killing because deer are delicate and wild are causing real damage in rural areas, as the reintroduction of wolves and bob cats is not practical in crowded communities with dogs, cats, and small children.

Thank you for your writing.

Thank you for your writing. I too have been faced with my love of gardening and the deer. We have reached a peaceful accord with a fence. They can eat what they want outside the fence, but inside the fence is my food and NoDeer garden. We are at equilibrium.

I used to duck hunt, but turned to shooting with the camera. Eating wild duck is a ritual in my family, a joyful one and we eat what we shoot. It is a delicacy, but I no longer take joy in the hunt and the kill; my joy is in the peace and wildness of the swamp.

Add new comment