Hope Cove. [o]

Barefoot walking has been credited with all kinds of medical benefits, from strengthening the nervous system to helping depression, even curing jetlag. Yet most people, myself included, rarely take their shoes off outside the privacy of their own home. Going barefoot in public is still generally frowned upon — and viewed as the preserve of eccentrics and tie-dye wearing fraternities.

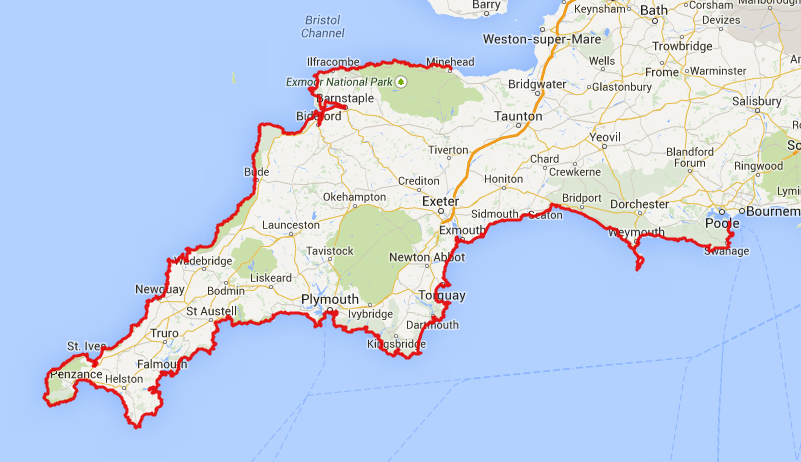

Are we missing out? When my uncle announced he was going to walk the entire length of England’s southwest coastal path, over 600 miles, and that he would be doing large sections of it barefoot, I decided to join him. I needed to find out more about why he was doing it, but also, I wanted to spend some time with him after what had been a difficult few months for my family. Not to mention, it was the start of summer, the sun was shining, and I was keen for an adventure.

My uncle isn’t easy to track down. I head for Salcombe, a small coastal town on the bottom of England’s southwest peninsula, where we have arranged to meet. I try to call him and let him know of my arrival, but can’t get through. He carries a mobile phone with him now, a very recent concession to the modern age, but it seems that this afternoon he’s out of battery life or signal.

I end up sitting in the passenger ferry port for a couple of hours. People come and go up and down the little slipway on to the open-topped boat that doesn’t really look like a ferry at all. I gaze across the narrow channel of water that separates Salcombe from East Portlemouth, the village on the opposite side of the estuary. I can see passengers waiting on the other side. Searching for my uncle’s tall silhouette, I’m also on the lookout for Woody, his Parson Russell Terrier, and the distinctive white wag of his tail.

I guess I’m one of those he is upbraiding, those who are “held back by fear or convention”.

I’ve retired to The Ferry Inn, where I sit in a window with a beer in hand. When my uncle finds me he plants a big kiss on my lips, his beard moist with condensation. He then asks to borrow 60p to pay the ferryman.

The next morning, after a night spent camping on the clifftop above Starehole Bay, we breakfast on Brazil nuts and rice cakes from his supply of rations and head west, towards Hope Cove. The sun is high and bright, a perfect early summer day. As he indicates the brilliant glister of the blue gold waves in the distance, my uncle remarks that “it’s almost psychedelic.” The South West coastal path unrolls ahead of us: a dusty pink line hugging tight beneath jagged rock formations and snaking along the abrupt contours of the coast.

My uncle takes his shoes off straight away. He casts a disappointed look my way when I fail to join him. I’m not quite feeling brave enough yet. As I follow in his wake up a steep ascent, I watch how he traverses the landscape. His feet touch the earth gently, almost tiptoeing as he moves from spot-to-spot across little islands of moss and sheep-cropped turf. He swerves around shards of stone that jut up from the path, moving in a slow weave. He seeks out the softest places, almost like he’s dancing.

The thick, hardened skin on the soles of his feet, and the deep cracks that line them, attest to how often he walks like this. In fact, he’s undertaking most of his journey this way, wherever there’s a natural surface, and the only shoes he’s brought with him are a thin pair of sandals; woefully inadequate, many might think, for the distance he’s covering with a heavy pack on his back. He tells me, however, that he rarely feels tired when he travels this way — “just completely refreshed and energised”.

A reasonable time for the South West coastal path is 7-8 weeks. [o]

Yes, he is evangelical about the health benefits of barefoot walking, and he’s not alone. One organisation, the Society for Barefoot Living, brings together enthusiasts from around the world; and academic reports published in titles including the US Journal of Environmental and Public Health have cited an almost endless list of its healing properties. Amongst the many benefits, going barefoot has been credited with reducing pain and inflammation, improving sleep, strengthening the immune and nervous systems, improving circulation, which contributes to its reducing effects of jetlag. The source of these elixir qualities lies in ‘earthing’, which, essentially, enables the earth’s energy to neutralise positively-charged free radicals that can cause all kinds of problems. Ultimately, it’s the same idea that underpins the need to ‘earth’ a power plug: our bodies conduct electricity, and so we need to be in contact with the earth to stay in balance.

“Going barefoot is our natural state,” my uncle says. “Yet most people spend nearly all of their lives cutting themselves off from that. They only ever do it when they’re on the beach, or on the lawn at home, but certainly not like this – cross country.”

Nonetheless, I’m hesitant to take my boots off. What’s the reason for my reserve? I guess I’m one of those my uncle is upbraiding, those who are “held back by fear or convention”. Shoes, and how we wear them, have a significance beyond the practical. Throughout history, they have symbolised wealth and status. Take, for instance, the ‘chopines’ of the 15th to 17th century, designed to keep high status wearers as far from the earth as possible. Going unshod has long signified, at best, humility, and at worst, destitution. For women, the notion of being ‘barefoot and pregnant’ points to diminished social standing — a negative public image that the practice hasn’t yet shaken.

I’m nervous, too, about injuring myself, or stepping in something unpleasant. “But if you live your life in fear, you’re not really living,” my uncle tells me. “You have to get over that.” He’s right, of course. I should take my boots off. But there’s a group of ramblers coming in the other direction, clad head to in the latest gear from North Face, so I decide to keep them on for just a few more minutes.

My uncle knows a thing or two about really living. He is closer to nature than anyone else I know. He hugs trees and interrupts walks to splash about in streams and fall asleep beneath appealing hedgerows. He swims naked in the ocean and bathes in the dew that accumulates on grass in the early morning. Through the winter, he works as a stonemason, crafting intricate designs with time and care, and in the summer he takes off with his pack on his back, laying his head wherever he fancies and never losing a sunny day to work commitments. Such freedom from the shackles of modern life can be both enviable and, occasionally — when you’re left waiting for him at a ferry port for hours — frustrating. It is perhaps this quality that for years, as a city dweller, has been a little alien to me. But as I have mellowed into my thirties, slowed down and begun to pay closer attention to the world around me, I think I’m beginning to understand him more.

[Author photo.]

I watch him striding ahead of me. He looks taller than I remember him being, wiry and muscular, his calves sprung-loaded for walking. His skin is tanned the deep brown that comes from being more outdoors than in. Straggles of greying blonde hair emerge from beneath a white baseball cap, and his beard has grown refulgent. The top pocket of his shirt is full of pens and pencil stubs — and a tiny notebook that he’s filled with recollections of his journey in his distinctive, curling cursive. It contains notes on the people he has met, places he has visited and, most importantly, meals he has eaten.

Although he has been in my life for more than 30 years, our relationship has recently changed. My uncle isn’t my blood relative, he is my aunt’s partner who she got together with in the 1980s.

Before Christmas, my aunt was admitted to hospital, suffering with cancer. She had been there for several days when they decided to get married. My uncle brought Woody with him to her bedside; his sister strung up bunting and passed around glasses of prosecco to the other people on the ward. It happened quickly. I wasn’t there, but in the photo I looked at afterwards my uncle looked smart in his best waistcoat, embroidered with orange dandelions. He was embracing my aunt who, even though she was so ill, was radiant and beaming.

Of course I’m much too modern to think that a technicality, the fact of a piece of paper, should make my uncle any more or less a family member than he ever was. But one way or another, it seemed high time to get to know him better. Walking barefoot with him is doing that.

It is a way of healing, too. On the night of the wedding in the hospital, my aunt died. When I had seen her a few days previously, although frail, she was animated and eager to share memories of happy moments in her life. These included her lying on her back in a haystack in Dorset, surrounded by glow worms, looking up at the stars. Another memory was of a yoga retreat in Spain in the 80s where she was forced, as part of the program, to rise at dawn and drink pints of sea water. It was so awful, she said, that she and her friend escaped and got plastered on herbal liqueur at the beach. “In the end,” she told me, “those are the things that you remember”

. She said she hoped that in the last moments of her life she would be able to close her eyes and think of being at the beach at Treen in Cornwall, 190 miles west of here. She wanted to imagine swimming out into the blue, not stopping.

Two barefoot walkers on the South West coastal path. [Author photo.]

“Do you want to take your shoes off now?” my uncle asks me, when we reach a quiet, green stretch of path.

I take my shoes off.

The ground is gritty but not unpleasant. I wriggle my toes and try to copy how my uncle moves – leading with the ball of my foot rather than the heel. It feels unnatural at first, but as I take more steps I’m conscious of the articulation of my soles against the earth. 33 joints, 26 tiny bones and 100-odd ligaments in each foot, shifting. It’s an energising experience: a kind of yoga for the feet. The ground is warm, I move from grassy patch to grassy patch, kicking up rabbit droppings with abandon. I get a thorn in my heel and it hurts. I hop about a bit, grimace and complain, but under my uncle’s guidance I pull it out and carry on. The bloom of blood mingles with dry dirt and is forgotten.

My uncle discovered the power of going barefoot in the 1980s, trekking with his brother and sister in the Scottish glens. Then he reconnected with it when he was in hospital several years ago. Following a tough winter, and the loss of a much-loved pet dog, he fell into a depression, which led to him being hospitalised. He felt, he says, a strong urge to get out into the grounds, to take off his shoes and stand on the grass. He attributes his swift recovery to this.

The benefits of walking barefoot aren’t, after all, just physical. It has been credited with reducing anxiety, stress and depression. Whether this is linked to the physiological effects the practice has on a person’s body, I don’t know. Perhaps it’s simply the impact of slowing down and paying attention to the data of your senses in a deeper way – a kind of mindfulness without the need for a fancy app or an adult colouring-in book.

“It was almost like she was having her last swim,” he says, “really making the most of it.”

We spend the day meandering along the coast, taking our sweet time. As he clambers to the top of alarming rock formations close to the cliff edge, my uncle’s toes curl into the fissures, monkey-like. He points at plants and names them: pink campion, stitchwort, bluebells, may blossom. I envy his gift for naming natural things. He reads the rural landscape like I read tube maps, constantly scanning for good camping spots and the edible fruit of hedgerows.

Later, we stop to swim at Soar Mill Cove in a tidal rock pool. When we dry off on the beach, a fine salt crust forms on our skin. My uncle remembers the trip he took with my aunt to Wales last summer, how she spent so long in the lake there. “It was almost like she was having her last swim,” he says, “really making the most of it.” Now he feels “that she’s free, and all around. She could actually be that bird flying, or that flower. She could be anywhere.”

I am barefoot only some of the time, but, by the end of the day, the nerve endings in my feet are alive, tingling and warm. We’ve covered a grand total of seven miles of coastline. It’s a distance most serious ramblers would scoff at, and yet I feel certain that in our wandering way we’ve experienced more of this place intimately than they ever would.

We reach Hope Bay in the evening, arriving beneath a great tangerine ball of sun dropping in the sky. Overlooking Milton Sands, we set up camp on a bank of spongy moss in the curve of a bench that has recently been erected. He tells me he’ll make a bench like this, engrave it with the names of my aunt and my grandparents, and position it somewhere with a view of the moors and the ocean.

My uncle says the worst thing that can happen when you’re barefoot walking is that you step in shit.

“So what? You wash it off, and carry on.” ≈ç ≈ç

AMBER MASSIE-BLOMFIELD is an arts producer and non-fiction writer. Her first book, Twenty Theatres to See Before You Die, is published by Penned in the Margins, for which she received the Society of Authors' Michael Meyer Award. Her writing has been published widely in periodicals. From 2014-18 she was Executive Director of Camden People's Theatre CPT), and won a Special Achievement Award at the 2018 Off West End Awards for her work there increasing diversity and access. She is a fellow of Birkbeck University and Royal Society of the Arts. She lives in Brighton, England.

If this article has been any inspiration to you, you might want to visit the author's uncle's crowdfunding site here — to assist he and Woody on their barefoot peregrination of the South West Coastal Path.

Comments

What a lovely piece. I'm a

What a lovely piece. I'm a bit of a dilettante compared to your intrepid uncle, but I've run barefoot (in minimal shoes, and also unshod) and it is a whole other world of sensation and pleasure, at least when you don't step on anything sharp. Thank you for a moving and inspiring account.

Add new comment