The Huaorani build group shelters in clearings using branches from the rainforest. [o]

Moi came to the United States of North America on a warm sunny afternoon, and though he hit the streets of Washington, D.C., at the evening rush hour, he walked in the city as he does in the forest—in slow, even strides. He kept his eyes on the ground and his knees bent, and he planted his broad feet deliberately, heel and toe, yet lightly as raindrops. It was the walk of a man accustomed to slippery terrain. I found myself stutter-stepping all the way down Pennsylvania Avenue, but Moi slid through the pedestrian horde like a fish parting water. He stopped only once, to study a squirrel climbing a maple tree: meat.

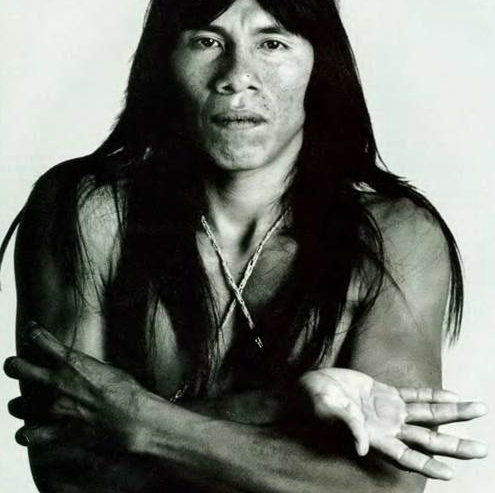

Moi wore dark khaki pants, a starched white dress shirt, a blue-and-gray striped tie, and brown leather shoes. The shoes were borrowed but the dothes were new, and, even if he was not entirely comfortable in them, he cut a handsome figure. In fact, except for unusually high cheek-bones, the leonine cut ofhis thick black hair-straight across his eyes and hanging halfway down his back and shoulders that threatened to burst the seams of his shirt, he looked like a typical tourist. Even in a city of international travellers, however, his journey was unique. It had begun deep in the Ecuadorian Amazon, in the homeland of his people, the Huaorani—a small but fearsome nation of semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers who have lived in isolation for so long that they speak a language unrelated to any other on earth. It had taken Moi nearly two weeks to reach Washington; travelling by foot, canoe, bus, rail, and air, he had crossed centuries.

Tucked into a handwoven palm-string bag that he'd brought from home were his passport, his toothbrush, his bird-feather crown, and a letter addressed to the President of the United States of North America. Moi had written the letter three times in a ten-cent notebook he always carries in his back pocket. The letter was an invitation to the President to visit the Huaorani [pronounced wow-rah-NEE]. He wanted the President to explain to the People, as the Huaorani call themselves, exactly why the United States of North America was trying to destroy them. "The whole world must come and see how the Huaorani live well," the letter said. 'We live with the spirit of the jaguar. We do not want to be civilized by your missionaries or killed, by your oil companies. Must the jaguar die so that you can have more contamination and television?"

"The soldiers will be on you like a boa on a tree rat."

At the White House gate, Moi reached into his bag and carefully removed his crown. It was made from owl, eagle, toucan, pafiot, and wild-turkey feathers, and when he jammed it down on his jet-black hair a thousand colors seemed to burst from the plumes. But the gate was closed, and for a long time Moi stood and stared silendy through the iron fence.

Then he said, "That house looks pretty small. Are you sure the government lives here?"

"The President lives here, with his family."

"Where are the soldiers? Are they underground?"

"Probably. And in back and inside."

He gripped the fence, as if testing its strength, and his eyes narrowed in calculation: he went into the Huaorani zone, as I'd come to think of it. When he returned, he said, "I believe I can climb this fence and reach the front door before the soldiers get me."

"It will not work, Moi."

"It will not work if I do not try."

"The soldiers will be on you like a boa on a tree rat."

"I will climb the trees and hide in the canopy. I will pretend I am hunting monkeys."

But I dissuaded him, at least for the moment, and we walked on. The sidewalks were full, and traffic roared.

"There are so many cars," he said. "How long have they been here? A million years?"

"Much less."

'A thousand years?"

"No. Eighty, perhaps."

He was silent then, and after a while he asked, "What will you do in ten more years? In ten years, your world will be pure metal. Did your god do this?"

Dusk tumed to night, and as we approached our hotel Moi stopped beneath a streetlamp. He pointed to the street. "More people, more cars, more petroleum, more chaos," he said. Then he pointed straight up at the light. "But there are the Huaorani, all alone in the middle of the world."

The Ecuadorian Amazon. [o]

Moi had been brought to Washington by a team of attorneys from the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, which, on behalf of the Huaorani, had filed a petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, an arm of the Organization of American States. Over the last twenty years, American oil development in the Oriente—as the Ecuadorian Amazon is known—has proceeded virtually without regulation. Every day, the petroleum industry dumps millions of gallons of untreated toxic pollutants into a watershed extending over fifiy thousand square miles of rain forest, and it has opened vast stretches of the region to colonization and deforestation. The impact has been so devastating that at least one tribe, the Cofán, has all but disappeared. Commercial oil production in the Huaorani territory is expected to begin sometime this year. The Huaorani petition charges that this will be ethnocide, and asks the commission to investigate, but it's a long shot, at best. Such an investigation would be beyond the scale of the commission's usual work, and, in any case, the commission has no powers of enforcement. However, its moral authority is enormous, and, long odds or not, an investigation could be the best chance the Huaorani have to avoid annihilation. The Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund hoped that Moi's testimony would persuade the commission to act.

Apparenty, this fact was not lost on the American Embassy in Quito, which often works closely with the petroleum industry. (ln 1992, the Bush Administration's designate for the post of Ambassador was the president of a Texas oil company.) Days before Moi was scheduled to testify, the Embassy denied him a visa, arguing that because he had no tangible assets tying him to Ecuador there was a risk that he would disappear inside the United States as an illegal immigrant. It could be argued that, on the contrary, Moi's assets run deeper than just about anyone else's in Ecuador, for the Huaorani hold legal title to a good chunk of the territory they have always occupied. But they hold that tide communally, and by Embassy standards this arrangement makes Moi a landless peasant.

At least, it did until the right question bounced onto the right desk at the State Department: Why was a plaintiff in a human-rights case being denied a visa? When I met Moi in Washington, one of the first things he did was produce his brand-new passport and show me the visa. "The Embassy changed its mind," he said. "It has invited me to visit your country for five years."

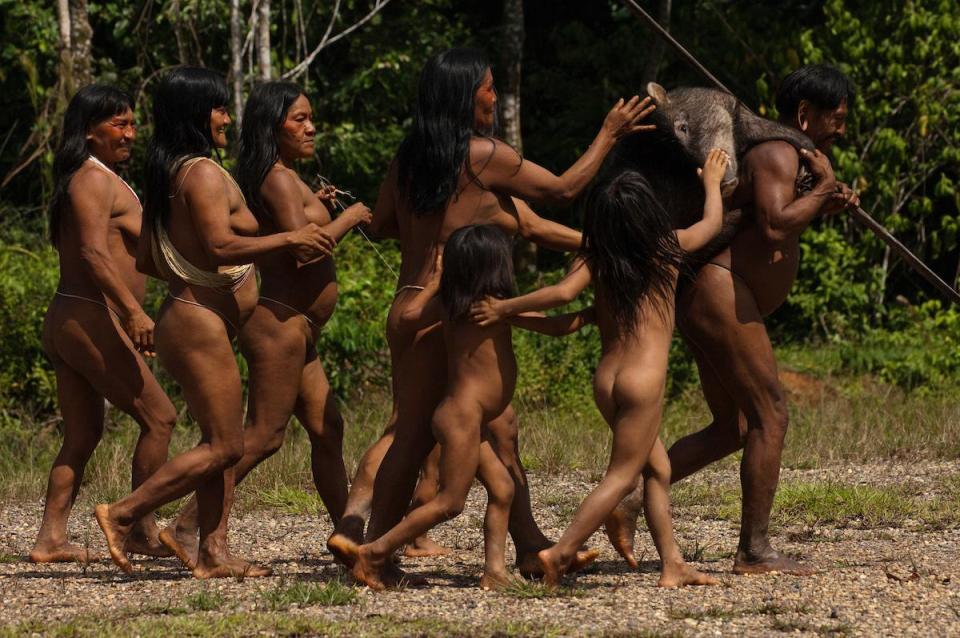

As Moi saw it, he was engaged in a war, and the Huaorani were ready to fight that war with spears made from the hardest wood in the forest—"spears that can kill fifteen men without breaking," he said. Indeed, anthropologists have called the Huaorani the fiercest people in the world. Though there have probably never been more of them than there are today—about fifteen hundred—they have, for as long as anyone knows, defended a territory the size of Massachusetts against all comers: the Incas; the Spanish conquistadores; the rubber barons; the armies of Ecuador and Peru; modern-day colonists and prospectors; and, always, their land-hungry indigenous neighbors, the Quichua and the Shuar, who together outnumber the Huaorani by almost a hundred to one. Biologically, the rain forest that the Huaorani occupy may be the richest place on the planet; to the Huaorani, it is the universe. But fighting the Company—the name that the Huaorani give all interests to whom the Ecuadorian government has sold the rights to the petroleum beneath their land—is something else again. Under Ecuadorian law, the Huaorani have no control over oil production and no share in its revenues. The Company plans to extract more than two hundred million barrels of raw crude from the Huaorani territory, and in its quest to exploit that oil it has revealed itself to be an enemy far more powerful than any the Huaorani have ever known: an enemy that, as Moi sees it, kills by destroying the source of all life, the forest itself.

The Amazon River, the largest drainage system in the world in terms of the volume of its flow and the area of its basin. [o]

Though it had been almost a year since I last saw Moi (we'd spent months travelling together in the Amazon), when he came to the hotel he greeted me in the Huaorani way, virtually without expression, as if only a few minutes had passed since we last spoke. "Chongkane," he said—that is what he calls me—and then he handed me his bag and his spears and walked into the room. Our relationship had been defined long ago, without words. In the forest, where I was helpless, he watched out for me at all times; in the city, I owed him no less.

We stayed at the hotel four nights. Moi discovered channel-surfing, baseball, the Washington Post, and modern warfare. Baseball, a game of spears and rocks, he enjoyed for its technique; beyond that, he found television useless. The Post he studied carefully each morning, mainly the airline ads (other than foot and canoe, small planes are the only transportation known inside the Huao territory) and the photographs. Of the latter, he was most taken by the somewhat violent shots of a clash in Russia. He asked me to translate the accompanying stories into Spanish—it is the language in which he and I converse—and peppered me with questions.

One morning, he asked, "The United States and Russia fought a big war, did they not?"

"Yes, they did. It lasted many years."

"Which country did they fight it in? Here or there?"

"Neither."

"That is impossible."

"They fought it in other countries."

"That makes no sense. That would be like the Huaorani fighting the Shuar in Quichua territory."

"Something like that."

He laughed. "That is a very stupid way to make war."

Moi spent most of the first night working on the statement he would make to the commission. He wrote it out in his notebook twice and then read it aloud, practicing his gestures. He would wear his shirt and tie, and over them his jaguar-tooth necklace, his string bag, and the reed tube in which he carried blowgun darts. "In the forest I wear this," he said, touching his necklace, "but your world wants me to wear this," and he tugged on his tie.

He read slowly, with little of the force or charm that came so naturally when he spoke. "Your ideas are good, but use your own words," I suggested. "Speak as you would without the paper."

"You mean speak like the jaguar," he said. The Huaorani consider the jaguar the most powerful force in the forest; as a "jaguar shaman"—a shaman with the ability to transform himself into a jaguar—Moi's grandfather is the most deeply revered man in the culture.

Later, exhausted, Moi told me he wanted to clean up and go to bed. I showed him the shower, but somehow it seemed inadequate. For the Huaorani, bathing is communal. In late afternoon, people all head down to the river, and they hang out there for what seems forever, soaping up, swimming, gossiping, joking, and flirting. By comparison, a hotel shower seemed soulless. Still, Moi disappeared into the bathroom for about an hour. I heard the water go on and off several times. Finally, he emerged, wearing only his shorts, his skin red as a boiled lobster.

"Tomorrow, I would like a new hotel room," he said.

"Why?"

"I would like a room that also has cold water."

He dressed himself completely and had me tie his tie. Then, fully clothed, he got into bed. Like many Huaorani, he drew no hard distinction between day and night. He would wake several times, to eat, to pace our suite, to analyze the new sounds he was hearing.

He pulled the blankets up to his chin. "Chongkane," he said, "will we win?"

"You will try your best."

"We must win or the Huaorani will disappear forever."

Then he closed his eyes and, as always, fell asleep in seconds.

"The Huaorani were ready to fight that war with spears made from the hardest wood in the forest." [o]

Moi had spent enough time among the cowode, or "cannibals"—as the Huaorani call all outsiders—to know that the Company could not be defeated by spears alone. Early in 1990, when he was twenty-four, and of an age to assume a position of authority within his culture, he and some other young Huaorani leaders founded the Organization of the Huaorani Nation of the Ecuadorian Amazon, or, in its Spanish acronym, ONHAE. For the Huaorani, a notoriously clannish people, ONHAE was an unprecedented attempt to develop a national voice. It almost worked. In March of that year, hundreds of Huaorani from across the territory came together to hold their first elections. Moi was elected Vice-President. He and the other officers spent the next three years crisscrossing the vast territory by foot and canoe, trying to organize their people. It was brutal work; Amo, the Secretary, was killed in the course of it, and the President, Nanto, had his spirit so broken that when his term of office ended, in February of 1993, he did not run again.

Moi, too, retired, because he believed that ONHAE should have new officers—that power should be passed on. But then he saw his dream undermined and, indeed, destroyed. He told me that the Company had bought the elections, working together with American evangelical missionaries, as it had done for decades. On Election Day, the Company gave the Huaorani helicopter rides, and when Moi's friend Enqueri became President it fitted him with dentures. Moi said that Enqueri was a good man but weak, because he'd been reared by the missionaries; they had a hold on him that could not be broken. Enqueri made a deal with the Company that not only sanctioned oil production but essentially put the Company in charge of Huao health and education—an arrangement that the Ecuadorian government, which has long considered the Huaorani situation a political embarrassment, was only too happy to support. 'We were sold like meat," Moi said.

So Moi had journeyed to Washington to invite the whole world to come and see what was happening to the Huaorani. The next morning, at his insistence, we made another attempt at the White House; once again, the gate was closed. Nearby, however, there were two life-size cutouts of Bill and Hillary Clinton. I explained to Moi who they were. He nodded, stepped between them, slipped his palm into Bill's, and turned stone-faced to the photographer. After the Polaroid developed, Moi studied it seriously, in the way the Huaorani often study photos: he held it upside down, sidewise, and at an angle, to be sure he understood its essence. ''Yes," he said. "That is me." Satisfied, he tucked it in his bag. Then we strolled past the Washington Monument. Moi assumed that it was an oil well, because in his part of the Amazon rain forest the only place one sees such an expanse of cleared land and such an immense structure is where the Company is at work. It made sense to Moi that an oil well would stand right in the heart of the center of power in the United States of North America.

I can't reveal what happened at the commission hearing that afternoon; having spent several months in the Huaorani territory, I was also asked to appear as a witness, with the understanding that I would not report on the proceedings. But I think it's fair to say this: Moi took to heart my suggestion to "use your own words." The hearing was in Spanish, which Moi speaks fluently, and when it came time to testify he indeed roared like a jaguar. However, he did so in Huaorani. The commissioners sat back, stunned. As I learned later, Moi told the commission that the Huaorani protected the forest for the whole world, and that they had never been conquered and never would be. By the time he reached his warning that the Huaorani were "the bravest people in the Amazon" and would defend themselves "with spears from all sides," he was half out of his seat with the intensity of his oratory. About then, one of the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund attorneys leaned over and said, very quietly, "Now say it in Spanish." Moi slipped into Spanish without appearing to miss a beat. "Please do not abandon us to the Company," he said.

When your sky falls," Moi said, "this will hold up the clouds."

When the hearing ended, about a half-dozen commission members gathered around Moi to introduce themselves. As it happened, Moi had brought several string bags with him from the forest. The bags had been woven by Huaorani elders. Each bag had taken about a week to make. The palm leaves had to be searched out, picked, and peeled; the inner skin was then boiled, dried, spun, dyed, and woven into a netlike, incredibly strong, and, to my eyes, subtly beautiful bag, which would last a generation or more. Moi had hoped to fetch about five dollars for each bag, and perhaps a dollar more for "transport." (Although the younger Huaorani men can sometimes find work as laborers outside the territory, most of the women and the older men depend on such handicrafts to earn a little cash for things like shotgun shells and malaria medicine.) As Moi figured it, there was no better place to start his sales campaign than with the commission. But the Huaorani are warriors, not traders; they are merciless to their enemies and generous to their friends; and within five minutes Moi had simply given away all the bags he'd brought. He gave away a spear, too, to the commission's executive secretary. "When your sky falls," Moi said, "this will hold up the clouds."

The next day, the commission said that although it was strongly interested in the Huaorani petition, it could not, under the bylaws of the O.A.S., conduct an investigation unless it was invited to do so by the host country. In this case, that invitation had to come through the Ecuadorian Ambassador to the O.A.S., who works out of the Ecuadorian Embassy. The Embassy tends to make the Company's interests its own. (Last December, after a group of Oriente Indians filed a one-billion dollar damage suit against Texaco, in New York, the Embassy intervened in an attempt to block the suit from being heard in the United States.) You can see the problem, the commission said. Perhaps Moi would speak with the Ambassador?

While the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund attorneys spent all the next day trying to arrange a meeting at the Ecuadorian Embassy, Moi put his time to good use. Speaking Spanish, he quickly developed a rapport with the hotel's service staff. He learned how to run the elevator, he stuffed his bag with free shampoo, and, as often as he wanted, which was often indeed, he was served a humongous dish the kitchen named the Moi Plate—a bottomless gob of chicken, shrimp, rice, potatoes, and "leaves," as Moi called lettuce.

Though his Spanish clearly served him well, Moi was determined to learn English, because he wanted to meet American women. He was convinced that until he could speak to them in their own language he would be ignored. However, in every place I have travelled with Moi women have seemed to appear out of nowhere and attach themselves to him. (Once, in Ecuador, I'd watched a young European heiress all but propose marriage.) As far as I could tell, Moi did nothing to encourage this attention. Rather, women left him paralyzed with shyness; they were the only force I'd seen, in forest or city, that inspired in him anything that might be called fear.

Chevron was fined $8 billion for polluting the Amazon in a history-making case. [o]

Moi never did get inside the White House, but he came close. A few hours before our train was to leave for New York, he settled his crown into place, adjusted his jaguar-tooth necklace, and marched through the metal detectors inside the Old Executive Office Building. He'd been invited to meet with the director of the White House Office on Environmental Policy, Kathleen McGinty, who had visited the Huaorani territory for a few hours last August, when the Company and the United States Embassy flew her into Enqueri's village. (A few weeks later, a photograph from that visit appeared in the Times; McGinty was wearing a Huao headdress and the somewhat startled expression that most cowode wear most of the time in the territory, as if they'd landed on another planet.)

Moi told McGinty what had happened after she left, when the Company and Enqueri staged a ceremony for the signing of the agreement that endorsed the Company's presence on Huaorani land. After the ceremony, Moi said, dozens of Huaorani fell sick with disease, and one little girl died. Furthermore, he said, many of the Huaorani were opposed to the agreement, but they hadn't been allowed to attend the ceremony. In the past, ONHAE would have held an assembly before making any such deal, and representatives from all parts of the territory would have come together and discussed it until consensus was reached. But, according to Moi, only Enqueri and a few others had read this new agreement, and only Enqueri had signed it. Many Huaorani believed it to be a deal for T-shirts.

McGinty assured Moi that the White House was interested in the Huaorani and would be keeping an eye on the situation. Though I, for one, had no doubt of her sincerity, Moi seemed disturbed as we left. He felt that he had failed, somehow. In the corridor, he said, "The Company can speak whenever it wants to, but this is the only chance the Huaorani will have to be heard. If only the government would come to the forest—if only it could see." He was lost in thought until we hit the street. Then he said that he was thinking of changing his name. Moi, he said, was a Huaorani word that meant "dream," as in a vision, but now it was too late for visions. He would change his name to Dica, because dica means "rock." "A rock can be struck many times, but it can never be hurt," he said.

Our last stop on our last day in Washington was the Ecuadorian Embassy, where, finally, a meeting had been arranged. Where the Old Executive Office Building had bustled with activity, the Embassy seemed a throwback to colonial South America and an authoritarian order that, centuries after the conquest, continues to dominate nearly every aspect of Ecuadorian culture. The building itself is haciendalike and cavernous, and a ghostly emptiness greets the visitor. The only life in evidence on the ground floor was huddled into a comer: a dozen of the forlorn Latin faces one sees throughout Ecuador, faces reflecting resignation to a long and most likely fruitless wait for an audience with whatever power it was that lay hidden an indication of the seriousness of the O.A.S. case that Moi and his attorneys were ushered into the Ambassador's office right on time for their meeting.

Strong coffee was served in tiny cups. The Ambassador is a small, dapper man with a rhetorical style that is common, in my experience, to virtually every bureaucrat in Ecuador: parry slightly, then thrust with an aggression meant to buckle the knees. As he sipped his coffee, he listened to Moi's proposition: Invite the O.A.S. to study the territory and, if problems were found, impose a moratorium on oil development until they could be resolved. When Moi finished, the Ambassador smiled and put down his coffee cup. In a voice that grew steadily more intense, he said that the Huaorani were not a sovereign nation; they were Ecuadorian citizens. Ecuador depended on oil for half its revenue, so to impede production was akin to treason. And how could Moi claim to speak for the Huaorani? Just two weeks before, their elected leader, Enqueri, had sat in the Ambassador's office. He had come to the United States with the Company and the missionaries, and he had seemed very happy with the agreement he'd made with them. As far as the Ambassador could tell, the Company was doing a fine job.

Moi listened impassively and, to all outward appearances, patiently. For the Huaorani, political discourse, such as it is, is a matter of long discussion aimed at achieving consensus; aggression means spears, and putting one's life on the line. When the Ambassador had finished, Moi had only one point to make: If the Company was doing a fine job, what harm could there be in an open investigation? Everyone could participate: the Company, the government, the Huaorani, the O.A.S., the whole world. Let everyone come and see. Let everyone speak.

The Ambassador was silent for a moment. Then he said, "Do not think for one second that there will ever be a moratorium on oil development. But I will talk to the commission and tell them about our discussion today. And then we will see."

"They hang out there for what seems forever, soaping up, swimming, gossiping, joking, and flirting." [o]

While we were waiting to hear from the commission, we took the train to New York. For the first hour, Moi amused himself by adjusting his seat. Then he practiced English: "Hello. How are you, Miss?" and "Good morning" and "Thank you." He leafed through a mail-order catalogue—jackets, shoes, watches—and asked the same question about each item: "Is this waterproof ?" He found Chesapeake Bay beautiful and added its name to a list he was keeping of cities and towns. After we entered the industrial corridor north of Delaware, however, his face lost its glow. We passed a field of giant tanks used for storing chemicals; to Moi, they looked exactly like the tanks the Company uses to store oil.

For a long time, he didn't say a word. Then he asked, "Chongkane, are there any Indians here?"

"No."

"Were there Indians here before the Company came?"

"Yes. There were Indians everywhere."

"Were they killed?"

''Yes."

"All of them?"

"Almost all."

From there to Pennsylvania Station, we rode in silence. Once in New York City, however, Moi perked up. Proceeding at his usual slow, steady gait, he slipped easily through the crowds milling in the station. Only one thing seemed to throw him. As we stood in line waiting for a cab, he bumped me with his shoulder and nodded toward two young women ahead of us.

"You are on your own," I told him.

He went into the Huaorani zone, as if to summon every ounce of courage he had. When he returned, he looked at one of the women, and said, in perfect English, "Hello." She smiled at him; he froze. Then he turned, looked me right in the eye, and said, "How are you, Miss?"

Over the next couple of days, we negotiated Manhattan carrying a nine-foot Huaorani spear. ("Cool," someone remarked on Forty-second Street.) When we travelled by cab, it protruded like a jousting lance, scattering pedestrians before it, and at the hotel it melted crowds. ("Good Lord," said the doorman.) Moi was impressed, but not overwhelmed, by the immensity of the buildings; perplexed by the terraces that grew forests high above the ground; and flummoxed by the city's pace. "In Ecuador, we wait all day for four o'clock. In New York, four o'clock comes with breakfast." Through it all, however, Moi remained utterly himself. One night, we ate dinner at a Mexican restaurant, near a drug-rehabilitation center. At the table behind us, several men and women were engaged in what might be kindly described as group therapy. They screamed and shook their fists at one another. Moi studied them carefully until a woman pitched forward and passed out on the table. Then he leaned over and spoke to her softly, in a voice filled with compassion. "Good morning," he said. "Thank you."

It is unlikely that Moi would ever disappear into the United States as an illegal alien. He finds life here pleasant, but he finds life at home thrilling. Eating in restaurants is no match for hunting wild boar. Moi's village, Quehueriono, is hidden in dense forest high on the crystal-clear Shiripuno River, in a breathtaking region of deep valleys and mist-shrouded hills backed by snowcapped volcanic peaks. In fact, Moi lives in the heart of what may well be the richest biotic land on the planet. Though the Oriente is no larger than Alabama, as many as twelve thousand species of plants are estimated to grow there, or roughly five per cent of all the plant species on earth. At a single research station, not far from Quehueriono, observers have recorded four hundred and ninety species of birds, or about two-thirds as many as are found in the entire continental United States; four hundred and seventy-three species of trees—roughly the number native to all of Western Europe—have been identified in a plot of forest about the size of two football fields.

''The lawyers will have to explain," I said, and took down the number.

Though the Oriente constitutes perhaps two per cent of the landmass of the Amazon basin, it plays an inordinately large role in the basin's ecology, because almost half the rivers that flow into the Amazon's headwaters originate there. What happens in the Oriente, in other words, resonates throughout the Amazon. This is a terrifying notion, considered in the context of American oil development, which has proceeded almost unchecked since Texaco perforated its first commercial well there, some twenty-two years ago. Since then, a three-hundred-and-twelve-mile pipeline that runs from the Oriente to Ecuador's Pacific Coast has ruptured at least twenty-seven times, spilling into the Oriente's delicate webwork of rivers, creeks, and lagoons more than one and a half times as much oil as the Exxon Valdez spilled off the coast of Alaska. According to Judith Kimerling, a former environmental litigator in the office of the New York State Attorney General who has spent most of the last five years investigating the impact of oil development on the Oriente, the petroleum industry is spilling an additional ten thousand gallons a week from secondary-flow lines and is dumping some 4.3 million gallons of untreated toxic waste directly into the watershed every day. People living in the oil-producing areas suffer from exceptionally high rates of malnutrition, spontaneous abortion, cancer, birth defects, and other health problems linked to contaminants. (A recent study of the water supply in the Oriente, made by a team of Harvard-trained scientists, found extremely high levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, an element of crude oil so toxic that the United States Environmental Protection Agency considers any amount at all to be an unacceptable risk.)

Thus far, oil development has hit other areas of the Oriente far harder than it has hit the Huaorani, but that situation is changing rapidly. Later this year, Maxus Energy, a Dallas-based company, which holds concession rights to the Huaorani lands, is expected to open the first of about a hundred and twenty commercial wells inside the territory. Before the project is finished, it will have completed a seventy-five-mile pipeline and ninety-four miles of access roads, and as it is sinking its wells it will add miles of service roads. This infrastructure will help open up to development, by any number of other oil companies (American concerns operating in the Oriente include Arco, Occidental Petroleum, and Oryx Energy), and to colonization, by any number of desperately poor settlers from outside, the rest of the Huaorani territory, and, indeed, the rest of the Oriente. By some estimates, the Oriente will be completely deforested early in the next century.

Over the next twenty years, Maxus will extract enough raw crude from the Huaorani lands to meet the United States' energy needs for about thirteen days. Unless something changes, soon, it seems safe to assume that by the time that oil is gone the Huaorani will be, too.

After two nights in New York, still without word from the commission, we flew to Oakland, where I live. Moi did so with trepidation: he had heard that there was no meat in California, that people ate nothing but leaves. We walked in the redwoods: Moi was astounded by their size but disappointed that they harbored neither jaguars nor monkeys. At my house, he turned the bamboo patch into a blowgun factory and stalked squirrels and pigeons, and he engaged me in a running debate about the globe in my living room: Why put a map on a ball? Maps were fl.at. If the world were round, the water would fall off.

Finally, the day before Moi was to leave, the call came from Washington: the Ecuadorian Ambassador had spoken to the commission and invited it to Ecuador, the commission had accepted. Though the Ecuadorian government had yet to put the invitation in writing, and thus make it official, the commission believed that this would just be a matter of time.

It was about then that Moi learned how to slap a high five. Later, he chanted the jaguar spirit into my home, to protect me until I could return to safety in the land of the People. Then he was ready to depart. "There is not very much to learn in the city," he said. "It is time to walk in the forest again." Then he said, in English, "Hello," and then he was gone.

Moi's visit occurred in the fall. Two weeks after he went home, the Ecuadorian government sent the O.A.S. a letter in which it said that there had been a misunderstanding; that it would not extend a formal invitation; and that, essentially, it saw no reason for an investigation. There was no way to get this information to Moi. As far as I knew, he was waiting in Quehueriono, ready to roar like a jaguar not only for the commission but for the President of the United States of North America and the whole world.

Then, in January, I received a collect phone call from Ecuador. The connection was awful, but I heard "Chongkane" come swimming through the static, and for a moment I was startled. Then I was worried. Moi spoke as he always did—directly, without introduction or niceties—but his voice had an urgency I'd never heard before. He had made his way to Quito, he said, to the house of a cowode friend, who had put the call through for him. He wouldn't stay long in the city. The government was after him. They were angry about what he had said in Washington. At the least, they would revoke his passport; at worst, he feared for his life.

Moi photographed by Richard Avedon, Oct. 8, 1994.

"When is the commission coming?" Moi asked.

''The lawyers will have to explain," I said, and took down the number.

"Tell them to call right away."

"I will. Be careful, Moi."

"The Huaorani live well!" he said, and hung up.

In March, a friend who works with the Huaorani (and whose knowledge of the Oriente once saved my life) told me, ''The word is that Moi is a dead man." He added that the military had recently picked Moi up for "interrogation." He was released after two days, apparently unharmed; still, I found myself wondering if l would ever see him again.

One of the ways I go to visit Moi is to travel by truck down an oil development road called the Via Auca, then by canoe up the Shiripuno River. The Via Auca is lined with oil wells and a pipeline, and right near the Shiripuno there is a large cluster of wells and a pumping station. If there is any one point in the long journey to Moi's home when I feel that I'm leaving one culture and entering another, it is when the canoe takes the first bend in the river and the wells and the road and the pipeline disappear behind me and I am surrounded by nothing but forest.

In January, the pipeline ruptured right where it crosses the Shiripuno, spilling so much oil into the river that it created a slick thirty miles long. But that was nothing compared with what had happened in November: one of the wells burst into flame and burned out of control for nearly a week. It was, by most accounts, the biggest fire ever seen in the Oriente. The oil-fed flames are said to have leapt so high that they dwarfed the great forest itself, and to have spread so fast that no man could outrun them. ũ

Used with the author's permission; this article first appeared in The New Yorker, May 2, 1994.

LINKS

Review of Savages, by Paul Trachtman, Smithsonian Magazine.

Radio interview with biologist E. O. Wilson on the need to protect the diversity of the Amazon.

JOE KANE is a journalist who writes for numerous publications such as The New Yorker, National Geographic, and Esquire. In addition to Savages (1995), he is the author of Running the Amazon (1989), a firsthand account of the only expedition ever to travel the entire 4,200-mile Amazon River from its source in Peru to the Atlantic Ocean. The book is listed on Outside Magazine's "25 Best Adventure Books of the Last 100 Years" and National Geographic's "The 100 Greatest Adventure Books of All Time". Joe is currently the executive director of the Nisqually Land Trust, the lead nongovernmental conservation organization in the Nisqually River Watershed, in west central Washington state.

Comments

Not a comment, but a question

Not a comment, but a question. What happened to Moi, was he murdered? If not what happened to him? And Nanto, did he continue his relationship with the oil company? Did his daughter survive? And Enqueri did he continue working for the oil company Maxus? Who speaks for the Huaorani now? Are the oil companies still extracting oil in that region of Ecuador? Thanks for writing an insightful and compassionate book. Thanks for opening my eyes.

We don't know the answers to

We don't know the answers to your good questions, but if you come up with anything, please let us know. Many thanks!

Add new comment