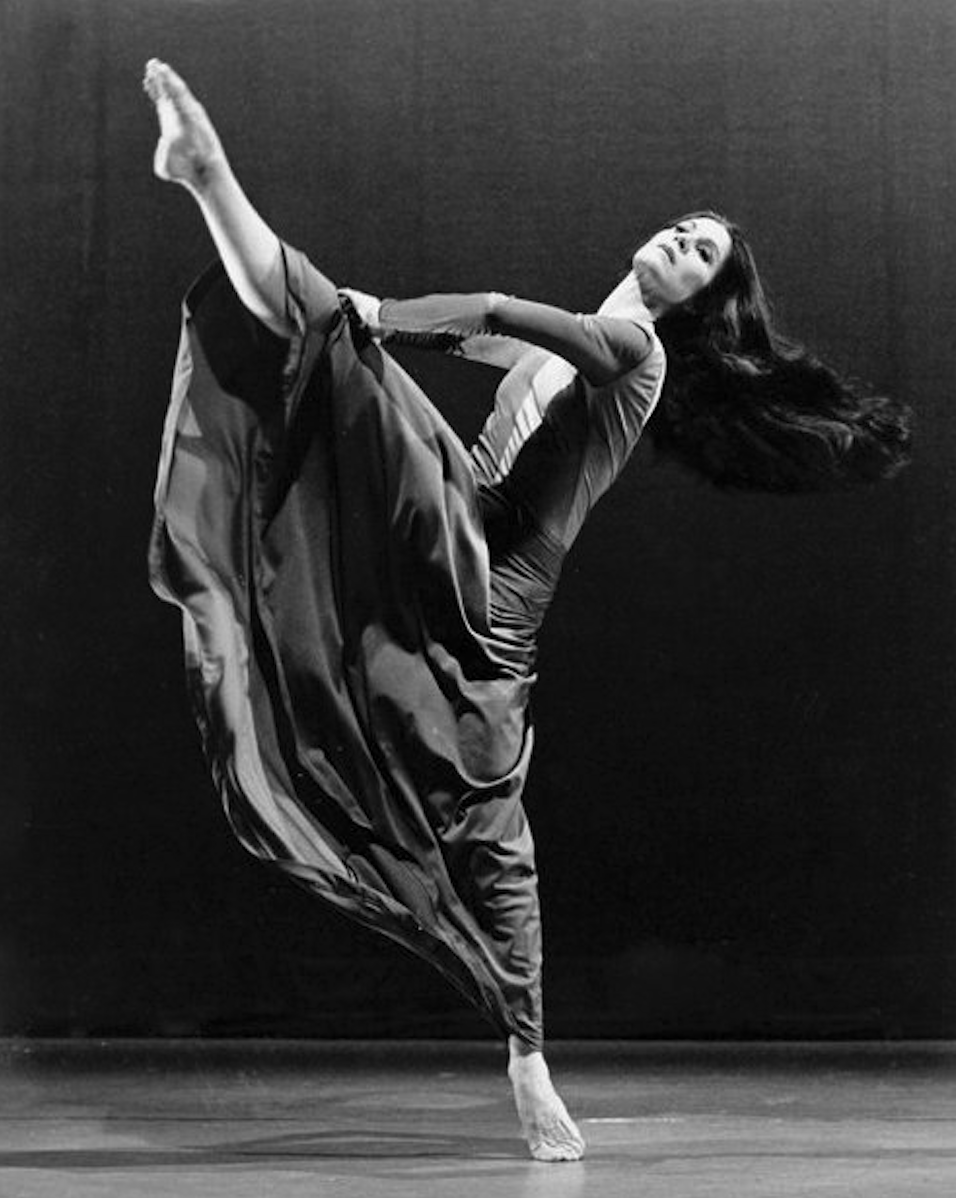

Moving the envelope. "Bennington offered a very serious degree in the performing arts, so there I was," said Beatty. At the American Festival of Dance, in the 1950s before she arrived. [o]

Watch the film . .

.

This is the transcription of the interview with Patricia Beatty about Martha Graham that took place in Toronto on April 3, 2015.

1. GROOMED TO DO SOMETHING IN THE WORLD

WHITNEY SMITH We're talking today about your experience and your knowledge of Martha Graham. Please give us the background that led you meeting her.

PATRICIA BEATTY I was at Bennington College [in the mid-to-late 1950s] because I wanted a creative education, and I knew that I wanted to dance and have a life in dance. But I wanted more than just to train in a studio; I wanted liberal arts, and Bennington offered a very serious degree in the performing arts, so there I was. This was in Vermont, by the way, a very progressive place, and [Bennington was] wildly expensive. And in my freshman year, the student-teacher ratio was eight to one. You were groomed to do something in the world, and it's still true. I did not know that this was a period when Bennington was concentrating on the arts, so I was there at the right time, unknowingly. It benefited me enormously, needless to say. So the freshman year, instead of studying Dance History 101, we had something called Structure and Style. That's very Bennington, not academic as academic is known.

It was not about appearing beautiful. It was not about design.

And so I heard all about this great giant of modern dance named Martha Graham. Well, we all knew that Isadora had planted the seed, Isadora Duncan [d. 1927], to move away from the ballet. And next came Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn (d. 1968, 1972], and Martha danced with both of them; in Santa Barbara she discovered them. And so I heard all about this great force, and I’d say, well, what about everybody else? (I didn't know how egalitarian I was going to be!) Well, I have to see how good she is. So, on the first weekend I go to New York, when there was a Graham season on Broadway. I went, and, of course, it was very powerful. I said, “Oh, she's so creative, this is amazing.” Having been brought up only on the ballet and jazz, right? Whoa.

The next year, I went to the next season and I said, but she's doing the same movement she did last time; I didn't understand that a choreographer develops a language of their own. I was taught that you can make up movement and it can be taken seriously, it can express what you want; it's not traditional, in other words. So, second year, I thought, oh gee, she's just doing . . . [mimics heady laughter]. The third time I went, I said, “Oh, my God, this is powerful theatre. This is equal to Eugene O'Neill and Aaron Copeland, all the other arts in America. This is mature work.” And, it was so relevant, it was so sensuous, it was compelling. It was not entertaining, it was compelling, and I began to sense the difference.

Bill Bales, Beatty's teacher Bennington. “Now you know what dancing is, and what it means to you. Now go get some more technique. You can get that anywhere.” [o]

2. GO GET SOME MORE TECHNIQUE

Still, when I graduated [in 1959], I knew I was headed for New York. My wonderful teacher, Bill Bales, a great, great composition teacher and life teacher. He said, the day I graduated, “Now you know what dancing is, and what it means to you. Now go get some more technique. You can get that anywhere.” That was such perspective! Kids today don't have that perspective.

So I go to New York, which in itself is a big journey, big encounter, but I was so excited. (I was green, still.) And I tried other places because I didn't want to follow Martha just because everybody said she was great, I wanted to find out for myself. So I went to all kinds of other places. José Limón gave me a scholarship and that was thrilling, but I didn't last there because much as I loved it, my body wasn't changing. And I ended up at the Graham School because even though I thought it was a very strange, neurotic place — and I was right — my body changed immediately; I could feel what was happening. And I said, “Oh, my God, you cannot lie with this movement. You cannot make it look like something. It has to be something.” In other words, it was the deepest I had ever experienced dance, and it's still true.

And the thing that really makes Martha Graham so extraordinary is that not only did she create a great original body of work, but she created a technique of dancing. Nobody in the history of dance in western civilization has done that. One person: she created it in order that dancers could perform her works. In other words, it came from the same place.

SMITH You're saying she was the one person?

BEATTY Yes. And she wasn't even a great teacher. She was just a force.

Martha Graham in 'Lamentation." Photo by Barbara Morgan. [o]

3. MY BODY STARTED TO CHANGE

SMITH So for people who aren't dancers, let's talk about how you developed this technique as a dancer, and how you came to understand what she was doing.

BEATTY Well, you come from two sides. You come from experiencing it — as training, studying that way. My body started to change, I could feel more power, more beauty, coming there in a month, than I had in any other school I'd been to. I knew how to make it look right, but I knew [this change] deep down. See, the Limón technique is based on principles called ‘fall and rebound.’ Well, I had such big energy that I would throw myself all over the place, like I had no control. But with Graham technique, you have to go inside, and that's exactly where I had to be. And then I found power. I found control, not from my head. It was organic.People didn't even use the word ‘organic’ then. I mean, her theatre values were so organic. There was no decoration.

SMITH Can you give us an example of this, to try and understand what you're talking about, about going inside?

BEATTY Some people said that Martha must have studied yoga, but she didn't, she hadn't. She was tuned in physically the same way, that deeply. And her technique did not start at the bar, doing exercises for the legs and whatnot; it started on the floor. And it grew, and it makes organic sense what she did. She also made it a ritual, not an exercise class. Emotionally and spiritually and artistically it had much more power. And she was laughed at. People made fun of her. They called her melodramatic, which is a relative term. They just weren't used to that much drama. Other dancers said, “Oh, those Graham dancers . . .” They were made fun of because it was so deep and so serious. It was the studio that was also called ‘the home of the pelvic truth.’ There were lots of good jokes.

SMITH So when you use the word organic, I think we understand that it comes from the soil, from the roots of what you're trying to build. Can you explain it a little more?

Born and raised in California, Isadora Duncan lived and danced in Europe and the Soviet Union from the age of 22. "You were once wild here," she said. "Don't let them tame you." [o]

BEATTY It's a very important word because it has to do with integrity. It has to do with wholeness: that every part of the body, every part that was onstage relates to one thing. In other words, the body is not trained in isolation. In ballet, the body is the arms and the legs; everything is trained separately and held together. In Graham, it starts from the centre, because emotionally, Martha said “That's where movement comes from.” Isadora Duncan said the same thing. This great big woman stood in front of the mirror and said, “Where does movement come from?” And that took the whole course away from the ballet. It was not about appearing beautiful. It was not about design. In other words, there was a natural beauty to the body. Now it had to be trained; there had to be some artistic influence, of course, sensibility. But, for instance, I know my work [came from it]. It’s seminal. Martha's technique, a lot of different people — Paul Taylor — came from it. Danny Grossman came from it. A lot of people have had their roots in it, in other words, and don't look like Martha. That’s very important. It's that deep and that organic and original.

4. NOTHING WORKS SEPARATE

SMITH We were talking about organic . . .meaning that nothing works separate. And that means this technique is much more emotional, and not the kind of emotion that you put on the body. That's false to Martha, it's very American, this, it really is. Only an American would have come up with this, I swear. It's true, and where Martha was most inspired was in the Midwest!

We tend to forget that Appalachian Spring, the historic American composition by Aaron Copland that premiered in 1944, was commissioned by Martha Graham and first performed by her company. [o]

SMITH Would you say there's a pragmatism to it?

BEATTY I would never use that word. But it means that it came from the earth. Martha really believed in the power of the earth. This is so feminine. This is the deep feminine. And I realized — rehearsing that piece you saw last month — my choreography came from my dancing, not from my mind. Of course my mind helped; I have to have imagination, a picture thing. But Martha started this. Her idea of choreography was expression from the body, not large designs of groups organizing steps. We don't even use the word step, we use the word movement — that's very telling. Most people think choreography is this other . . . orchestration. Of course, it is that. But Martha started something. She couldn't help it, that's who she was. And she thought of herself first as a dancer. It’s very interesting to me, because probably I do, too. I see myself in all my dances. When I teach a work of mine, or choreograph a new one, I have to teach so much about dancing. And somebody said, “Well, it's like the Yeats quote: 'How can we tell the dancer from the dance?' ” That's it, and that's powerful stuff. But it takes a lot of work. It takes a lot of work. In other words, it is really not entertaining, it's something else.

5. DO YOU REALLY HAVE TO DO THIS?

SMITH So let's go back to this notion of an artist developing their own language.Tell us a bit more about aspects of that language that we in the audience see?

BEATTY I can tell you at the beginning, David Earle — my cohort, wonderful choreographer, much more prolific than me — he was putting together beautiful movement, that Martha had created, and organizing it into wonderful dances. And I said, “Dave, we're supposed to find our own movement.” This is a girl who's graduating from Bennington, right, who was taught to be an individual and be creative and find her own. And he said – David's a very intelligent guy — he said, “But dear, nobody here has even seen it.” And it's so beautiful. I said, “Okay.” Right? And he evolved. It takes time to evolve. But I worked very hard to try and find my own movement, not anything like . . . (no, I can't say that). The roots of the movement were the same: the principles of contraction and release. Contraction is a rounding of the spine, that's not simply what it looks like. Martha said, “it takes at least two years to learn.” It's technically very effective and emotionally very powerful, and that's the one thing she's given to dance that never existed before, and that's really what made it powerful. And today's dancers aren't doing it at all, because it's too intense.

Patricia Beatty, David Earle and Peter Randazzo, founders of Toronto Dance Theatre, the late 1960s.[o]

SMITH Okay. So what you're saying is that dancers – and I'm a person who doesn't know dance really, I've never done dance – is that most people would be sort of told, or shown, what a movement is, and what Martha was saying is: you develop a way of working with your body in which it's not only the aesthetic output of what you're doing when you're moving your body, but it's emotional . . .

BEATTY . . . that’s right.

SMITH Was that new?

BEATTY Oh, yeah. People thought they were doing it, but nobody did it to the level she did, and with the depth that she did, and with the originality that she did — and that's what made her work powerful. But, the poor darling, when she started out, her friends were saying, “It looks ugly compared to the ballet.” You see, parallel and flexed and serious, her hands like that. Even her friends were saying, “Martha, do you have to do this?” Well, you know, my parents: “Do you really want to do this?”

In other words, she created a new aesthetic. That goes on in the history of art, any art. But even though we really are at the end of the line in the arts, because we're the body, we're thought of as entertaining and frivolous and exciting, but not really capable of communicating the deep truth of being a human being. Martha changed that. And José did it himself, too, José Limón. It was a great period. You see the body is the most immediate . . . you are your instrument. That’s the only art form like that, well, the voice, the voice, singer. An actor has part of it, but a dancer is completely one’s self. I mean, Marion Woodman said: The body is the unconscious in its most immediate form. Wow! That's powerful. And Martha tapped right into that, and choreographed the Greek myths from a woman's perspective. She made all the psychologists go and restudy everything. Before the word feminist — I am sure she never heard of it, she couldn't help it, she was just a powerful woman — her way was more emotional and physical, and less spiritual and intellectual.

Patricia Beatty rehearsing Gaia (1989) with Mirian Braaf. " Isadora could see America dancing. Martha could sense. I can see what somebody could be. [Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann.]

6. ENCOUNTERING MARTHA

SMITH Let's go back to your encounter with her. Tell us about how you first met her.

BEATTY So I'd seen her on stage, and I had an actor boyfriend who I took to a season. He took one look at her and he said, “Oh, my God, there's no one else on stage.” And she was just sitting there — at the age of 64, or whatever she was — and it just reaffirmed to me: this is a powerful woman, okay? Unfortunately, she was wildly alcoholic. Martha never had the support emotionally. She had financial support later by Batsheva de Rothchild, but at the beginning, she had to go out on her own. Roosevelt invited her to the White House and she had to go raise the train fare. Yeah, this is a pioneer.

So I was taking her classes, but she wasn't teaching; her dancers were teaching. Occasionally, she would teach, but she was in another dimension most of the time or drunk, the poor woman, you know, problem. But she would say phenomenal things, because she had a poet’s soul. She became not a great person; she was a great artist, but not a great person. And I understand why now. She was very manipulative, because anybody, to me, who is manipulative thinks they can't get what they want directly, they have to do it indirectly. And I realized that so many women are like that. I tend to be forthright, haha, because I don't want to be way, and I pay the price for that, too.

You're going to be very beautiful one day, but your body is still locked.

I was short sighted, and because I was so eager, I used to take class, up near the front, not in the front row — because then you have to remember everything — but in the second row. And one night, Martha came in, somebody else was teaching but she came in to visit one of her classes. I thought, oh, wow, here I am, five feet in front of her. And people were scared of her. Well, some part of my Taurian determination said, “I'm not going to be scared of this woman.” The whole point is she is human, she's not superhuman, she's human — but that was tricky. And after class, oh, my God, she called me over. She didn't ask my name, she asked me where I had studied, and I said Bennington. And she said to me two things. She asked me to put my hand on her back, under the shoulder blade, and she said, “This is the promise of wings, this muscle.” And she put her hand on mine, she said, “You see, there's nothing there yet, dear. Now you have to go and work.” I knew what she meant, she was talking about the spiral, she's talking about this [stretches her arms out flowingly, turning her shoulders]. And she said to me, “You're going to be very beautiful one day, but your body is still locked.” Well, I went home, two feet off the ground. I can see a locked body very quickly. I just needed time.

She [was using] intuition so much at the time. Any great artist is a bit psychic in that way. Isadora could see America dancing, and she was right. And Martha could sense. I can do that now, I can see it, I can see what somebody could be. That’s why I was a good teacher, not because it was passing on craft — it's way more than that.

To be there when these works were being performed at night, and be able to take class in the morning, it was so rich, the experience, it's fed me. That and the impulse from Bennington to get the mind used correctly, and get the confidence.

Patricia Beatty . . . at work. [Photo by Andrew Oxenham.]

7. THE GRAHAM LEGACY

SMITH What's the legacy of Martha today?

BEATTY It's confused at the moment. It's only in the hands of people like myself and David [Earle] and other people in Japan, and around the world. There are people practicing, evolving, but she was a great pioneer, and she had to give her life to make a difference. She made dance grow up, and it's a bit adolescent again. So did José Limón. They were like our parents.

SMITH So finally, so what did Martha give you?

BEATTY She opened the door, I'm sure. She said this is the road. I took it. It's possible. “Oh good, nobody's done that in Canada, that's what I'll do.” And yeah, it wasn't that hard, it's just as long as you're willing to work when nobody knows quite what you're doing. But I heard all her stories. And when I hear about people talking about needing to feel safe before they can choreograph. I never heard of such a thing, not in the 60s. I had no idea that an artist was supposed to feel safe. You were supposed to risk, you were supposed to give yourself to something. And I'd seen it done, and it was so powerful and so beautiful that.

The other thing about Martha, she was eloquent with words. Most dance people and yoga people are not very good with language. She spoke beautifully, she wrote beautifully. Now, her biography is a bit the way she hoped it had been in her life [laughter] — there was a lot of imaginative stuff. But because she was a poet, she couldn't help it, she couldn't just write facts, that's too boring for her, I'm sure.

And so, to write poetry, what I've done in the last few years — since my body said, we've had enough — it's not so unnatural, it's not so unusual to me, because, she didn't write poetry, but her dances were. ≈ç

Whitney Smith and Patricia Beatty at the launch of the book Wild Culture: Ecology & Imagination, in Toronto in 1991. "In 1986," writes Smith, "I was going around talking about starting a magazine called The Journal of Wild Culture, and when I told Patricia she said, "Oh, I like that. I'll give you some money for it." The $5000 she gave us made it possible to print the first issue, which cost almost exactly that amount, and with that funding a crew of volunteers was formed and we got busy figuring out what it would be. A year later we were on the magazine racks with a print run of 5000 and began to accumulate subscribers. From the first issue onward Patricia Beatty's name appeared on the masthead as 'Eminence Verte.' Thank you, Patricia, for helping to make it happen.

PATRICIA BEATTY spent her life as a dancer, teacher and choreographer. She was the co-founder of the Toronto Dance Theatre and received the Order of Canada in 2004 for her work in modern dance. Since retiring from making new dances in 2004, she turned to writing poetry. Her books include Windwords: Poetry and Writing on Dance and, on the art of choreography, Form With Formula: A Concise Guide to the Choreographic Process, which is in its fifth edition. Slow Words Dancing can be ordered from ws at wildculture.com. Read other articles and poetry by Patricia Beatty in these pages.

WHITNEY SMITH is the Publisher/Editor of The Journal of Wild Culture. He lives in Toronto.

Comments

This was very moving and…

This was very moving and informative. I had studied nothing but ballet since I was 4, with a bit of Israeli folk dance, but at 14, my life changed I was accepted into the High School of Performing Arts (FAME) school in NYC. I was a ballet major as a 14 year-old sophomore. That meant we had ballet 5 days a week and Modern, Graham Technique, 2x. It started to become evident to the faculty that at 5'4" with an Not Ballet Body (I am an Ashkenazi Jew of Russian, Ukrainian, Austrian and Hungarian roots, grew to 5'7" by senior year) and not a lover of pointe shoes, that maybe my trajectory should be modern dance. I switched departments in my junior year which isn't done very often, but I was where I was supposed to be. I embraced the Graham floor, tilts were my thing. The technique fit perfectly on my body. I continued to study with Bertrum Ross and performed in the company of Henry Yu. I got a scholarship at Alvin Ailey, even though I took a workshop with Martha Graham herself in 1976. Auditioned for a scholarship, and even though everyone considered me a Graham dancer, nothing… So I got a scholarship at Alvin Ailey and was embraced there. Studied lots of techniques with those elite instructors, including Pearl Lang. Brief stint at NYU where Stuart Hodes was the Department Chair; Bertram was teaching and invited me to Perform a piece at Riverside Church. Was exposed to Cunningham and Limon as well, but auditioned for and was accepted to a 2 yr, commitment to AA lll, aka The Alvin Ailey American Dance Center Workshop. Was blessed to be there when Mr. Ailey Choreographed "Memoria" for the late Joyce Trisler upon her untimely death. I later danced with The Clive Thompson Dance Company where we performed at Jacobs's Pillow, 8/1982. Took workshops there with the Paul Taylor Company and felt like that would be where I could find a place, but didn't happen. Came very close to Ballet Hispanico. I was 23, when I quit modern dance, although I did perform with Al Perryman and Shirley Rushing at Symphony Space and later BAM. Such a hard hill to climb but I would never forget or regret it. As Patricia Beatty states, Martha Graham changed the course of dance. I currently work for The NYPL Jerome Robbins Dance Archive Division. flowslaw@yahoo.com, Amy Meisner, NYPL, Heidi Latsky Dance, MSW, SAG AFTRA.

Dear Amy, Thanks so much for…

Dear Amy, Thanks so much for sharing your comings and going in the complex, difficult and rewarding world of dance. Fascinating to hear how you intersected with so many masters, as Patricia did, drinking in the various influences, different and various yet all of the same piece: the ever evolving art of movement, dance and choreography. — Whitney Smith, Editor

Add new comment