Vancouver, British Columbia . . . Canada's "California, Here I Come!" [o]

"To describe the beauties of this region will on some future occasion be a very grateful task to the pen of a skilled panegyrist. The serenity of the climate, the innumerable pleasing landscapes, and the abundant fertility that unassisted nature puts forth, requires only to be enriched by the industry of man with villages, mansions, cottages, and other buildings. — Captain Vancouver

PART I

A Tax that Would Solve the Housing Crisis

Eliminate all taxes but a levy on land, said Henry George. Here’s why it would work.

In Vancouver, responses to the housing crisis fall into two camps: there are those who would increase supply and those who would limit demand. Both points of view have merit and both are needed.

But mostly overlooked in this debate is the real problem. It’s not that houses cost a lot. They don’t. Building a house in Vancouver costs roughly the same per square foot as in 100 Mile House [a town of 2000 in the interior of British Columbia]. It’s the land under homes that cost a lot. And land, because they are not making any more of it, is particularly susceptible to speculative pressures.

This isn’t the first time that the cost of urban land has spiralled beyond the reach of average wage earners. During the last “Gilded Age,” between 1870 and the advent of the First World War, land prices also rose dramatically. A bold solution came out of that time, championed by a popular political economist. His name was Henry George.

The real drag on culture, George argued, were people whose gains came passively by just sitting on a resource, doing nothing to it as its value rose.

GEORGE AND THE SINGLE TAX MOVEMENT

Henry George was born in Philadelphia in 1839. He was the second of 10 children in a lower-middle-class family. George started off as a journalist, working mostly in California, but with a brief stint in Victoria during his 20s. One day in 1871 on a horseback ride, he stopped to rest while overlooking San Francisco Bay. He met a teamster, and to make small talk, he asked how much land nearby was worth. The teamster didn’t know how much exactly, but said there was a local who was willing to sell his property for a $1,000 an acre. It was an epiphany for George.

“Like a flash it came over me that there was the reason of advancing poverty with advancing wealth,” George later wrote. “With the growth of population, land grows in value, and the men who work it must pay more for the privilege.”

George would champion the Single Tax movement, which has renewed relevance today given how urban land values are pushing housing costs more and more out of reach. George argued for the elimination of income taxes, taxes on sales and taxes on productive capital like machinery or buildings. There should only be one tax, George said, and that would be on land. To our modern ears this sounds irrational and our skepticism is largely a testament to how savagely his ideas were attacked at the time — an attack that endures to this day.

George’s hypothesis was this: land, since it gains its value passively (just by sitting there without adding anything to production), should be very heavily taxed. This would reduce or eliminate the tax burden on the labour of wage earners, the profit of owners and the buildings and machinery that makes production possible.

If you have a bit of exposure to political economy, you might recognize something unique about this formulation. While Marx pitted workers against owners, Henry George united them. To George, workers and owners were on the same side. By working together, both made the world a better and richer place. The real drag on culture, George argued, were people whose gains came passively by just sitting on a resource, doing nothing to it as its value rose.

“On the Brain – Mr Henry George” (1892), Phil May. Henry George: ‘Like a flash it came over me that there was the reason of advancing poverty with advancing wealth. With the growth of population, land grows in value, and the men who work it must pay more for the privilege." [o]

What George found most outrageous was that the value of any piece of urban land didn’t come from the effort of its owner; its value reflected past labour and enterprise performed on surrounding lands. Yet most of the gains from all this creative effort went to the land owner/speculator with very little to the people who actually created that value. In the case of Vancouver, current land prices are high because of all the good work done and taxes paid by previous generations of citizens. But are these citizens or their children reaping any reward? Most outrageously, land owners/speculators often gained the most by leaving their urban land empty and thus useless. Being useless, the land was often not taxed, even though its value steadily increased by the growth of the surrounding city.

George argued that taxes should be shifted to land and away from labour and productive capital. With land heavily taxed, it would be in the interests of land owners to find the most productive use for it. It would also mean that inflation of land prices would be mitigated, as land purchasers would know that heavy taxes came with owning land. Thus, the tax shift would both reduce taxes on productive activities and make land cheaper to put to productive use.

Do you find George’s plan reasonable? If so, you would join the many millions who agreed with George during his lifetime. He became famous throughout the English-speaking world before his life was cut short at 58 by a stroke. His book Progress and Poverty sold millions of copies, even outselling the Bible during he 1890s.

IS LAND A COMMODITY?

But what happened to George’s ideas? Why didn’t they take hold?

George was fiercely opposed by the landed gentry of his time, the very same people — the Vanderbilts, the Rockefellers — who were gaining fantastic wealth through passive gains on land. They responded to the Georgian surge by funding entire academic programs to crush the Single Tax movement’s popularity, paying carefully selected academics to muddy George’s case. One such program was the “Chicago school” at the University of Chicago, still a hugely influential source for conservative economic thought today (for example, the famous neoclassical economist Milton Friedman, economic adviser to both Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, taught there).

The Chicago school and other “liberal” think tanks successfully removed George’s qualitative distinction between land (in his view, inherently unproductive) and labour, enterprise, machinery and buildings (in George’s view, productive contributors to society).

Now, classical economists treat land as a form of capital, equal in productive value to other capital goods — such as apartment buildings, factories or railroad rolling stock. These economists were successful because the rest of us can no longer see the distinction between “passive” land and productive labour and capital. Without this distinction, our thinking is too muddled to see how land, in the hands of speculators, impedes the development of an equitable and productive Vancouver.

Figure 1. Map of the U.S. showing counties indicating value of land therein. As one would expect, urban areas have the highest value per county. Similar images are not available for Canada but would indicate the same patterns. Max Galka, Metrocosm.

Figure 2. Map of the U.S. showing the same information as in Figure 1, but with counties sized to conform with the total value of land in that county. The overwhelming value of urban lands is thus more clearly illustrated. Similar image for Canada not available but would show the same exaggerated pattern. Max Galka, Metrocosm.

NO LOVE FOR LAZY LAND

If you’re with me so far, you’re ready for another word that has been exiled by classical economists: the rentier. The word rentier is also making a comeback, in line with the revival of Georgian thought. This is no surprise. A rentier is one who gains wealth through passive actions. Land speculators, who add to their wealth by letting the value of land rise and/or collecting ever higher rents for the use of land, are rentiers.

The English landed gentry of yore were probably the most famous category of rentier. But the term applies to anyone who gains wealth passively. It’s a useful distinction, and one that we hear more and more. The wealthy are often called “job creators” on the assumption that those who gain wealth do so through their investment of entrepreneurial energy and money into business activities. In the process, job creators provide work and income for wage earners. Henry George would agree. He applauded the “job creators.”

But sadly, because of the work of classical economists, we lump active entrepreneurs together with passive rentiers. While it’s fair to celebrate Elon Musk and Steve Jobs for their success as job creators, it’s not so appealing to similarly celebrate those who passively use their wealth to acquire more wealth, a wealth that is typically taxed at a very low rate, if it is taxed at all.

We are talking about more mundane but crucial work in every field — from food services to teaching to law and medicine.

In most countries, the largest tax burden falls onto the backs of wage earners in the form of income tax. Not very Georgian. Profits acquired through land sale are typically taxed at much lower capital gains rates, with advantageous real estate loopholes available to bring the tax burden on land sales to zero in many cases (for more see Trump, Donald J.).

Here in Vancouver, we see how land is increasingly forcing housing out of reach of wage earners and sapping the economic strength of the city. Productive, well-educated, creative wage earners can no longer afford to live here. As they move away, the capacity of the city to generate new enterprise is also diminished. We are not just talking about high-tech startups, though they too are affected. We are talking about more mundane but crucial work in every field — from food services to teaching to law and medicine. The price of land has priced out every profession except real estate agents.

Vancouver is on track to become a place for the rich to park money and for the rest of us to visit as a tourist now and then — the Monaco of North America. A grim fate, but an avoidable one.

Henry George had it right. For Vancouver to survive as anything other than a tourist resort we need to tax land to cut off fuel that feeds the fires of land speculation and use the proceeds to create secure housing for wage earners with ordinary incomes.

PART II

Fixing Unaffordability Means Embracing Non-Market Housing

Jane Jacobs taught us to hate public housing, but the problem was how it was done, from urban design to social policy.

Taxing land makes sense, but how can this solve Vancouver’s housing crisis?

Given the apparently inexorable increase in the asset value of land (as detailed in part one of this series), secure and decent housing seems impossibly out of reach, especially for Vancouver’s working millennials.

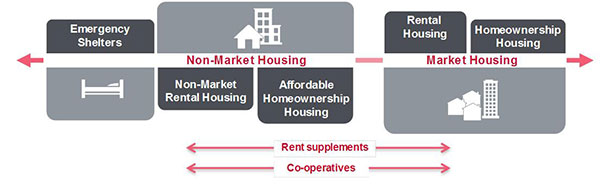

It’s time to revive a type of housing we’ve all but abandoned: non-market housing. Non-market housing is not the same as social housing or public housing. Non-market housing is any housing protected from market forces, thus offering affordable rents or ownership in perpetuity. Housing co-ops, land trusts and nonprofit housing corporations are all variants of non-market housing. But sadly, we no longer supply much in the way of non-market housing. Why? It’s partly because “public housing” — particularly the kind built in the U.S. — gave it a bad name.

DESTRUCTION IN THE NAME OF URBAN RENEWAL

Urban designers, architects, politicians and community activists have been highly critical of non-market housing for at least five decades. In the U.S., public housing was virtually non-existent before the Second World War. Very poor immigrants flooded into American urban areas and found lodging wherever they could, mostly in crowded and dilapidated urban districts, forming slums.

It wasn’t public housing that was bad; it was the way it was done, from urban design to social policy.

Slums were originally called tenement districts for their many walk-up apartment buildings. These were attractive areas when they were built, but over time became the housing of last resort for the poor. After the Second World War, public officials collectively decided that these decaying urban districts were beyond saving. For the first time, laws were passed that allowed public agencies to purchase “derelict” buildings at “fair market value” without consulting owners. If owners argued, the courts would adjudicate their claims and, as records show, would largely side with government. Owners, often derided as “slum lords,” had few defenders, so political opposition to “slum clearance” was weak.

Thousands of individual buildings were bulldozed during this era of “urban renewal,” along with the tight interconnected street networks which served them. In their place came widely spaced tower blocks in the Radiant City model. Streets were minimized to make way for pedestrianized green spaces, inspired by Le Corbusier’s illustrations. The results were disastrous. Most U.S. urban renewal public housing districts became dangerous zones that all avoided, all but those who had no other housing option. Why?

Jane Jacobs, author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, had the answer. She deftly described how traditional city streets worked and why eliminating them and the buildings attached to them was such a bad idea. She used the Greenwich Village district of Manhattan as her alternative case study to prove her points. The district was very similar to those bulldozed by the champions of urban renewal. In short, Jacobs taught us to hate public housing. But it wasn’t public housing that was bad; it was the way it was done, from urban design to social policy.

A word of caution is in order before proceeding: The failures of American urban renewal were extreme.

"Non-market housing is any housing protected from market forces, thus offering affordable rents or ownership in perpetuity." [o]

In other countries, the results of post-war urban redevelopment efforts were not so tragic. English new towns, often antiseptic and dull to the eye, were not as dangerous. Swedish housing blocks, just as slavish to the Radiant City model as their U.S. counterparts, did not rapidly decay. Canadian public housing projects were not the tool of racial and class segregation they became in the U.S.

Architecture and urban design certainly contributed mightily to the failures of public housing projects in the U.S. But many argued rightly that the greater problem was the extent that U.S. housing projects concentrated only those who were hopelessly mired in poverty, and that this concentration of social handicaps in one place only made them more crippling.

Fuelled in part by Jacob’s prescient critique, many notorious U.S. housing projects were abandoned, deemed irredeemable by virtue of their ignorant design. The most notorious example was the Pruitt Igoe housing project in St. Louis — designed by Minoru Yamasaki of Hellmuth, Yamasaki, & Leinweber, also architect of New York’s World Trade Center towers — which was completed to great fanfare in 1956, only to be blown up 20 years later by the housing authority. The site still sits vacant, a symbol of both a social and urban design failure (see here).

Our Vancouver example of this style housing can be seen at the Raymur Street housing project in the Strathcona neighbourhood. This large project is the only completed portion of what was to be a much larger urban renewal effort, the bulk of it never executed. Were it executed as designed, there would be nothing left of Strathcona, once considered a slum, but now one of the most desirable neighbourhoods in the city.

Le Corbusier’s plan for Paris, featuring his trademark scheme of widely separated tower blocks set in green space. While never executed in Paris, the plan was replicated hundreds of times across North America and usually failed. Jane Jacobs correctly identified the problem: Corbusier had treated humans as if they were machines who only needed ‘machines for living.’ [o]

SLUM REPAIR?

While many people remember the housing failures, there have been numerous successful housing project rehabilitations that are less well-known.

In the 1990s, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development led an effort to correct the glaring deficiencies of Radiant City-inspired U.S. housing projects. The initiative was called Hope VI.

Some of the most poorly designed buildings, usually tower blocks, were demolished under this program. Many low-rise structures were kept, redesigning them with tweaks like private front yards and private entries protected by modest porches, making them compatible with Jane Jacob’s principles so they looked like townhouses on a traditional city street. New streets were inserted across parking lots and greenswards to recreate a traditional city small block pattern.

And to overcome the stigma and ill effects of concentrated poverty, the projects required residents to be from a mix of incomes.

Consequently, many of the new rehabilitated units were to be sold. Residents would be homeowners not renters. Ironically, this successful attempt to improve public housing made it less public. By this we mean no criticism. We mean only to show that we find ourselves — planners, designers, and involved citizens — agreeing with those who argue that the only good housing is privately owned housing, be it market rental, condo or single-family house.

MARKET FAILURE?

So what are we to do when the market pushes land prices out of reach for wage earners?

Is density the solution? In a previous Tyee article, co-author David Beers and I suggested a strategy called “hiving,” that would allow any family making an average income or above to (just barely) afford to buy a Vancouver home. The thinking is simple. Land costs are too high for our average wage earners. The solution is to split up the land pie. In order to make the typical single-family lot affordable, you need to cut into five or six pieces. These could be rental or strata or some combination. This may sound like a lot of density on a lot, but you can find the same density in craftsman-style homes in Vancouver’s Kitsilano neighbourhood. But sadly, even with extreme effort, our computations showed that such homes would still only be affordable for those with median incomes or above. What of everyone else?

A deteriorated public housing complex in New Orleans that had 724 units, of which only 144 were occupied, was redeveloped with HOPE VI funds and other financing. The new development has 460 rental units (193 public housing units, 144 units for residents with local median incomes, 123 market-rate units). Another 22 units, scattered throughout the development, were offered for sale at prices affordable to residents with incomes up to 60 per cent and 80 per cent of the area median income. U.S. Housing and Urban Development.

Perhaps we could wait for a global recession to bring land prices back within the reach of wage earners. To be fair, it could happen, as it did in the U.S. in 2007. But since then, land values regained lost ground and are back to what was then considered stratospheric heights.

Or we could consider accepting a difficult possibility: a healthy housing market may never come back. We haven’t seen this kind of struggle for secure housing in the past 100 years. In Canada, Australia and New Zealand this past decade, average housing costs in major metropolitan areas jumped between 100 and 200 per cent!

If evidence of market failure becomes more apparent, our assumptions about the housing market must change. We must move beyond the simple reading many understood from Jacobs: public housing bad, private housing good.

In line with economist Henry George’s thinking (see part one in this series), we now have a situation where the rentiers are able to extract maximum gain by acquiring, holding and collecting rents from land, up to the almost limitless point where urban crowding returns to levels not seen since the 1920s. Average rents and mortgages are beginning to consume well over half of average incomes. Developers are building increasingly smaller homes to squeeze as much as possible out of the land. The housing situation for millennials today is nothing like what their parents had to face.

In such times, ideas that were once the ravings of radicals are now both practical and necessary. To house wage earners we must, as Henry George would suggest, tax land — both to reduce speculative pressures and to supply the funds necessary to build non-market housing for the disappearing middle class.

Happily there is a precedent for this. It is Vienna, where for exactly 100 years they have taxed land to build housing. Sixty per cent of Vienna residents now live securely in non-market housing. We examine their model in the third and final part of this series here.

PART III

How Vienna Cracked the Case of Housing Affordability

Vienna has a 100-year history of building public housing for all. What can we learn?

It’s hard to admit a healthy Vancouver housing market may never come back. As evidence of market failure becomes more and more apparent, we look to Vienna, where over 60 per cent of its residents live in city-built, sponsored or managed housing. How does this work? Can it be replicated elsewhere?

Nothing happens overnight, so let’s take a look at the long evolution of the Vienna model, which begins exactly 100 years ago.

VIENNA IN THE LANDLORD'S DAY

Vienna, during the last days of the Habsburgs, demonstrated its wealth in the form of impressive building façades.

But behind the façades was a grimmer reality: workers crowded 10 to a 300-sq.-foot flat. Many slept four to a bed. Some workers used their beds in shifts, hiring out sleeping space during the day while the principal tenant was at work — all to pay the usurious rents. Are we heading this way?

Significantly, officials during the Red Vienna period — unlike leftist parties in other parts of Europe — never set out to remove or even cripple capitalism by nationalizing property.

This Vienna was a city run by and for the landlords, wealthy owners of lands that had once been farms but now sprouted apartment buildings. Males of wealth, most of them landlords, were the only residents who could vote; they numbered 60,000 of Vienna’s two million residents at the dawn of the First World War.

With public policy so heavily tipped to landlords, renters had no protection. One-month leases were common and rents could be raised at any time with no recourse. Evictions were immediate, without cause and without adjudication. The gravity of this housing crisis and the plight of the people can be measured by the number of the homeless. In 1913, over 461,000 people lived in asylums (homeless shelters by another name), an astonishing quarter of the population. About 29,900 of these homeless were children.

While what Vancouver is now experiencing is nowhere near this bad, there are echoes. Here, the development industry wields outsized power over our elections, land speculators are reaping the benefits of our collective city-building efforts, homelessness is on the rise and wage earners are experiencing housing stresses that force them to accept insecure accommodations in crowded dwelling units.

When the housing market starts to fail, perhaps it’s time to implement state-driven solutions. This is Alt-Erlaa in Vienna, where 60 per cent of housing is city-built, sponsored or managed. [o]

When Austria and its allies were defeated in the First World War, the Habsburg monarchy collapsed. Universal suffrage followed; voting rights, once held by only two per cent of the population, were now granted to all, regardless of income or gender. This coincided with a dramatic leftward shift in Vienna’s politics, but in an unusual form. The war was unkind to both victors and vanquished, destabilizing democracies and monarchies alike. The Russian Revolution and subsequent 75-year reign by communists is the most well-known consequence, but many other governments were similarly destabilized.

For the next generation, citizens throughout Europe separated themselves into political camps ranging from Marxist internationalists on the far left to fascist nationalists on the far right, unleashing inevitable internal conflicts and the eventual conflagration of the Second World War. Austria’s political trajectory was more moderate — but only at first. The Viennese political left gained power with universal suffrage and the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and it retained this power until global economic constraints and the rise of Italian and German fascism led to a fascist takeover of the Austrian government in 1934. The relatively short period between 1917 and 1934 is called the “Red Vienna” period for the socialist leanings of its city leaders.

Significantly, elected and appointed officials during the Red Vienna period — unlike leftist parties in other parts of Europe — never set out to remove or even cripple capitalism by nationalizing property. Instead, they used a taxing strategy to meet their social ends and their most important achievement was providing decent housing for every resident. How did they do it?

THE CITY DEVELOPER

A number of policy and taxing policies made Vienna’s housing system possible. Even before the Red Vienna period, a key policy was imposed that was crucial to the city’s later success: strict rent control. The government had imposed it to prevent war wives from being evicted while their husbands fought at the front. It was never repealed. The government outlawed raising rents beyond a minimal amount and, in the presence of extreme currency inflation, made it less profitable to build new rental stock.

Reumann-Hof, a pioneer social housing complex built in 1923 during the Red Vienna. [o]

Ordinarily, this would be a very bad thing for affordability, as rental stock is usually less expensive per month (in the short term at least) than home ownership. Thus, policies that impede the construction of rental housing are generally frowned upon. This is true here in Vancouver, where successive city governments have gone to herculean lengths to induce the private market to produce new rental stock — through subsidy, relaxed development taxes or density bonuses. The city has been nominally successful, reversing a decades’ long decline in purpose-built rental starts; but the monthly rents charged for these new market-rate units are unaffordable for all but the upper tier of renters.

Vienna provides an interesting counterpoint. Because rent control disincentivized the private development of rental buildings, landlords were, for a time, removed from the market for urban land. Consequently prices finally went down, allowing the city to buy land at a much reduced price; often it was the only buyer in the market.

The city quickly became the dominant developer of new housing. Vienna had the wisdom to retain the city’s best architects and developers to design and build the new projects, employing experts who had honed their skills in service to the private sector to build non-market housing.

A fifth of Vienna’s new housing built during the Red Vienna years was social housing for the poor and disabled. But the bulk of the new housing was for wage earners and their families, to be owned and managed by co-operatives or non-profit housing corporations. Non-profit housing corporations operate just like for-profit housing corporations, except that their profits are poured back into operations and they are obligated to keep rents in line with incomes.

HOUSING DEMOCRACY

Even though the city was able to keep land prices down, land and housing still cost money. In the late 1920s, about 30 per cent of Vienna’s annual budget was spent buying land and financing housing construction.

Where did that money come from? Mostly from taxes on private property and land. They were levied on private apartment buildings and progressively increased with the assessed value of each unit. Very high taxes were also levied on vacant land, giving owners extra incentive to sell.

The Vienna model gives us hope for a housing system that can still align with average incomes in the face of global speculative pressures on land.

These policies stripped land speculation out of the marketplace and did so very rapidly. Doubtless, any attempt to replicate the Vienna strategy where faith in the “free market” remains strong would provoke emotional debate. But the gravity of the housing crisis that Vienna faced, and the efficacy of their solution, is beyond dispute. Is Vancouver approaching this same point?

Taxes supporting housing were eventually more broadly distributed, including a portion of income taxes now dedicated to housing. Resident Viennese had no problem supporting these taxes because they received secure housing that’s much more affordable than most of the developed world. Rents in Vienna are a quarter that of similar units in Paris.

Vienna also developed a system for working with non-profit development corporations that compete with each other for city sponsored projects. The city acquires the land for a project, establishes the housing goals and project pro forma and publishes the amount of financial subsidy to be supplied. Stakeholder groups judge the proposals submitted in response and decide which project team of architect, builder, developer and management entity has the most intelligent response.

This competitive process ensures that projects are distinctive and varied — a dramatic departure from the process for building public housing in many other countries, where mediocrity would seem to be the goal.

PERPETUAL AFFORDABILITY

Vancouver has been called the world’s most unaffordable housing market, at least by some measures. Vienna’s housing innovation was spurred by its own housing crisis a century ago. Is it time for Vancouver to act and build many thousands of non-market housing units? It would be a favourable time to do so. The provincial and federal governments are poised to support affordable housing once again, a responsibility largely abandoned since the 1990s. Vancouver has a strong claim to funds from these higher levels of government, given that it is B.C.’s main engine of economic growth and Canada’s third largest urban centre.

What can we learn from the Vienna example? Vienna treats land like the precious community asset that it is. We can acquire and keep land in the hands of the people who live on it. We should never sell city-owned land. And like Vienna, it would be crucial for Vancouver to purchase more land on behalf of non-governmental housing providers, whether they be churches, co-ops or charitable organizations.

The city also has powerful levers like zoning regulations and development taxes. Currently, Vancouver collects taxes on development through development cost levies and community amenity contributions. In the past, these taxes have been reduced to incentivize the creation of market-rental units that developers would not otherwise build because of high land costs. But that strategy is both inefficient and fails to ensure affordable housing in perpetuity. Community amenity contributions and development cost levies can and should be retargeted, and increased as much as possible, to provide funds for non-market housing and to reduce speculative pressures on development lands. Together with these revenues and provincial and federal funds, the city could jumpstart the creation of non-market housing for city wage earners in the bottom half of the income scale.

The Hundertwasserhaus public housing project in Vienna by painter and architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser. [o]

Taxpayers need not worry. With an initial period of subsidy, intelligent land use controls and policy and taxing levers, a sustainable housing system can be built that would eventually return the money back to the public sector — and thus the taxpayer. Assuming Vancouver wage earners continue to earn a reasonable salary, they can certainly pay a third of their earnings for housing, and thus repay construction financing and maintenance costs.

The Vienna model gives us hope for a housing system that can still align with average incomes in the face of global speculative pressures on land. Far from closing out the free marketplace, the Vienna model shows that they can complement each other. Development land is still cheap in Vienna (relative to Paris, at any rate) for both the city and for private developers. It is precisely the presence of the city in the land market that keeps it this way. The best Viennese developers work with the city to build outstanding housing projects one year and for private interests the next. The result: a city with an outstanding, successful model for creating more non-market and market affordable housing.

As both the Vienna model and Henry George would suggest, the problem is forever and always the cost of land. Burdensome land costs, and the rentiers who gain massive wealth by passive land speculation, are the real enemies — not developers, not our homeowners, not our public officials.

A plan to house up to half our wage earners in decent homes protected from the vagaries of the unshackled land market is our only choice — if we are committed to avoiding the fate of Monaco, a pretty place to park money and visit every now and then.

If we don’t want Vancouver to go down this path, then perhaps we should heed Henry George’s advice: tax land and use the proceeds to build the housing we need. ≈ç

PATRICK CONDON has worked in sustainable urban design for 25 years, first as a professional city planner and then as a teacher and researcher. He is the James Taylor Chair in Landscape and Liveable Environments at the University of British Columbia. He and his research partners have collaborated with the City of North Vancouver to produce a 100-year plan to make the city carbon-neutral. His two books Seven Rules for Sustainable Cities (2010) and Design Charrettes for Sustainable Communities (2007) are published by Island Press, Washington, DC.

Add new comment