Bringing back the traditional Indigenous knowledge of kelp farming in Cordova, Alaska is part of the regenerative economy work of the Nature Conservancy in the state. Photo by Ash Adams. [o]

WHITNEY SMITH Can you give us an example of a project your organization is working on that helps disenfranchised communities find their way past racist policies in finance sector?

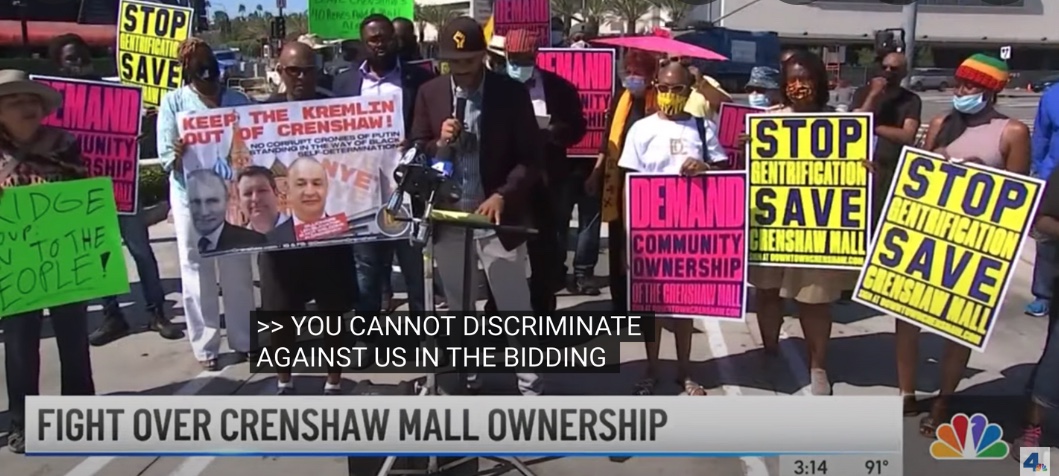

DAVID LEVINE I'll start with Crenshaw in East Los Angeles, a predominantly black community. To reclaim and revitalize their community and local economy, leaders in the community formed a project called Downtown Crenshaw Rising. So, looking around for opportunities, when a shopping mall there came up for sale, they decided to try and buy it and make it into a centerpiece for worker owned co-ops and cultural, arts, and community-led activities for all sorts of learning. With their leadership and ours and others’ support, we were able to help catalyze the raising of enough financing to make them the most competitive bidder. We had been working with them and people in their inner circle have helped them, in partnership with others, raise about $70 million towards the $120 million, much more the real estate developers who were vying for the property had to offer. Still, the owners wouldn't sell it to them.

They were battling the status quo. In this case it was structural racism in financial institutions, developers, politicians, and government bureaucracy.

SMITH Why was that?

LEVINE Because of structural racism and related biases. Due to that, they turned part of their attention elsewhere in their community and purchased an important and historic property in L.A.’s center of Blackness, Leimert Park Village/AfricaTown!!! It’s less than a half-mile from the Crenshaw Mall and right across the street from a soon to open Metro station. The site was home to the Total Experience, a legendary nightclub with an incredible history that had recently burnt down. Instead of the property falling into the hands of speculators, it will be built from the ashes of the club and include 50+ units of affordable housing with community-serving commercial space on the ground floor. It’s a good example of a community led initiative with broad and diverse support that got around the problematic issues of status quo investment policies.

SMITH How do you get involved to help communities like Crenshaw?

LEVINE A key part of our mission is to work with communities that have been historically underserved, if not outright beaten down by forms of structural racism and neglect. As you can see with Crenshaw community, they were battling the status quo. In this case it was the structural racism of financial institutions, developers, politicians, government bureaucracy — the obstacle for too long and for too many communities, especially communities of color.

SMITH Where else are there projects similar to this?

LEVINE This movement is gaining real momentum all over the place. The Native Conservancy in Alaska is working with the Indigenous-led effort to claim the rights to protect the oceans as they advance kelp farming. The Rosebud Sioux Tribe's project is establishing the largest Native-managed bison herd, which will have a profound impact on people and planet or efforts in Chicago, Trenton, Appalachia and elsewhere. All of these efforts are pieces of the collective effort that will help us build a restorative, inclusive and sustainable economy. One of the main ideas is to bring as many stakeholders together as possible — along with leadership from these and other communities — into collective force to shift housing, economic and community development.

Though the Crenshaw community offered a higher bid than competing real estate developers, the owners wouldn't sell them the mall. [o]

SMITH What are you doing to work with banks and financial institutions who are still driven by biased policies?

LEVINE One of the members of ASBN is Barclays Bank, who joined when they and a few other banks decided to commit to not finance private prisons. First let me add some context about private prisons, which have grown exponentially. In some states have become major businesses and employers, and they are driven to encourage moving more and more people — particularly people of color — into the prison system. Many people of color end up in the prison system because we're not investing in education, we're not investing in job training, we're not investing in entrepreneurship and growing economy in a just and sustainable way. So, in that case, these prisons reinforce the need to keep being filled up with more and more people. So, when we got word that Barclays was going to help with the underwriting of private prisons in Alabama, we decided to try and talk to them. Then we found that the announcement was going public. So we said, number one: that being part of our organization means a commitment to work towards a more just and sustainable economy, and one piece of that would include the case of Barclay’s commitment to not finance private prisons. So we issued a press release announcing that were giving back the membership money of all members who were economically supporting the prison industrial system.

SMITH Any response from them?

LEVINE That was on a Thursday, and on Friday they told the press that they were going to think about their decision to finance the prison. By Monday morning, it became national story and then an international story, appearing on Bloomberg News, Financial Times and elsewhere. So, on Monday, Barclay’s Bank announced that they were pulling out of the deal. Consequently, no other banks would step up to finance the private prisons in Alabama project. Now the Governor and some in the state government are trying to use federal funds to finance the private prisons.

Forbes magazine: "Toxic Alabama Private Prison Deal Falling Apart With Barclays Exit..." [o]

Forbes magazine: "Toxic Alabama Private Prison Deal Falling Apart With Barclays Exit..." [o]

SMITH I’d expect this kind of success did not just happen because you read something in the news and made a few calls. Can you give us a bit of background on how it occurred?

LEVINE Some of our member businesses and investor leaders had been involved in prison work for quite some time and they had formed a coalition. They were tracking this closely when they came to us, which gave us the opportunity to be fully informed, right up-to-the-minute. The executive director of Social Venture Circle and I were on the phone multiple times, and made the decision together to return Barclay’s membership; then we got our team on board to do the media work pushing this out. Our decision to return their significant membership fees became a big part of the story. In not supporting private prisons, they purported to be following Environmental Social Governance criteria. In the media, ASBN was called 'the ESG police’ for holding companies accountable for their actions, and that organizations like ours and other investors were paying attention. It had a huge impact. Suddenly other banks were thinking twice before going ahead to finance these kinds of deals. More and more people are watching, more and more bank customers, and that matters. So, alongside the people working on the private prison campaign for many years, this kind of effort made it big news. The result was that those who had declared they were committed to sustainable principles ended up taking the right action.

This shift in consciousness wasn’t the sole cause that created the shift, but it created a foundation from which good organizing could take root.

SMITH In ideal terms, let's say, in the next 10 or 20 years, what would you like to say to young people who are reading this?

LEVINE The biggest one is, how do we accept the fact that we're living with others, and while we see diversity in nature as beneficial, should it not be in society as well? How do we have that mutual respect, that ability to be able to work to be able to understand others, to try to communicate with others, to try and find a way for things to be fair, across all the differences we have with each other? If we're able to do that, it's not a matter anymore of pushing someone, or the planet, down so I can rise up, but to be able to understand our mutual responsibility to the commons. Understanding how to interact with others, working to understand the perspective of others. I am not suggesting that everyone is about to agree with each other; that's not necessarily what we're striving for. Rather, it's an attempt to work on oneself to try and understand one's own behavior and way of thinking.

One example has been the greater acceptance of LGBTQ+ and the path to gay marriage in the United States. This shift in consciousness wasn’t the sole cause that created the shift, but it created a foundation from which good organizing could take root. How many people stopped smoking because their kids told them. Children learned that it's bad, that it was not healthy, then asked their parents why they were still smoking. Add to that good organizing, media work, lawsuits and public policies and the shift has become monumental — in spite of the massive campaigns by the tobacco companies for decades to deceive the public about the dangers. People died because they believed those messages.

SMITH And the key to unlock these structural issues in one sector, with its system of reinforcing itself while keeping others and the planet down?

LEVINE It is time for big changes. The work ASBN does is based on building a movement of diverse stakeholders, stakeholders that embrace sustainable and just business and investor principles. If we couple that with a wide range of connected strategies — from movement of capital, shifting of capital, storytelling, community revitalization efforts, to especially the protection of our democracy — we can be on the path to solving some of these severe problems. A just economy requires these things. ≈ç

DAVID LEVINE has worked as a social entrepreneur for over 30 years focusing on the development of whole systems solutions for a more sustainable society through building strategic partnerships and broad stakeholders initiatives. Previously, he was the founding director of Continuing Education & Public Programs at The Graduate Center, City University of New York, and from 1984-1997, founder and executive director of the Learning Alliance, an independent popular education organization. He lives in New York City.

Add new comment