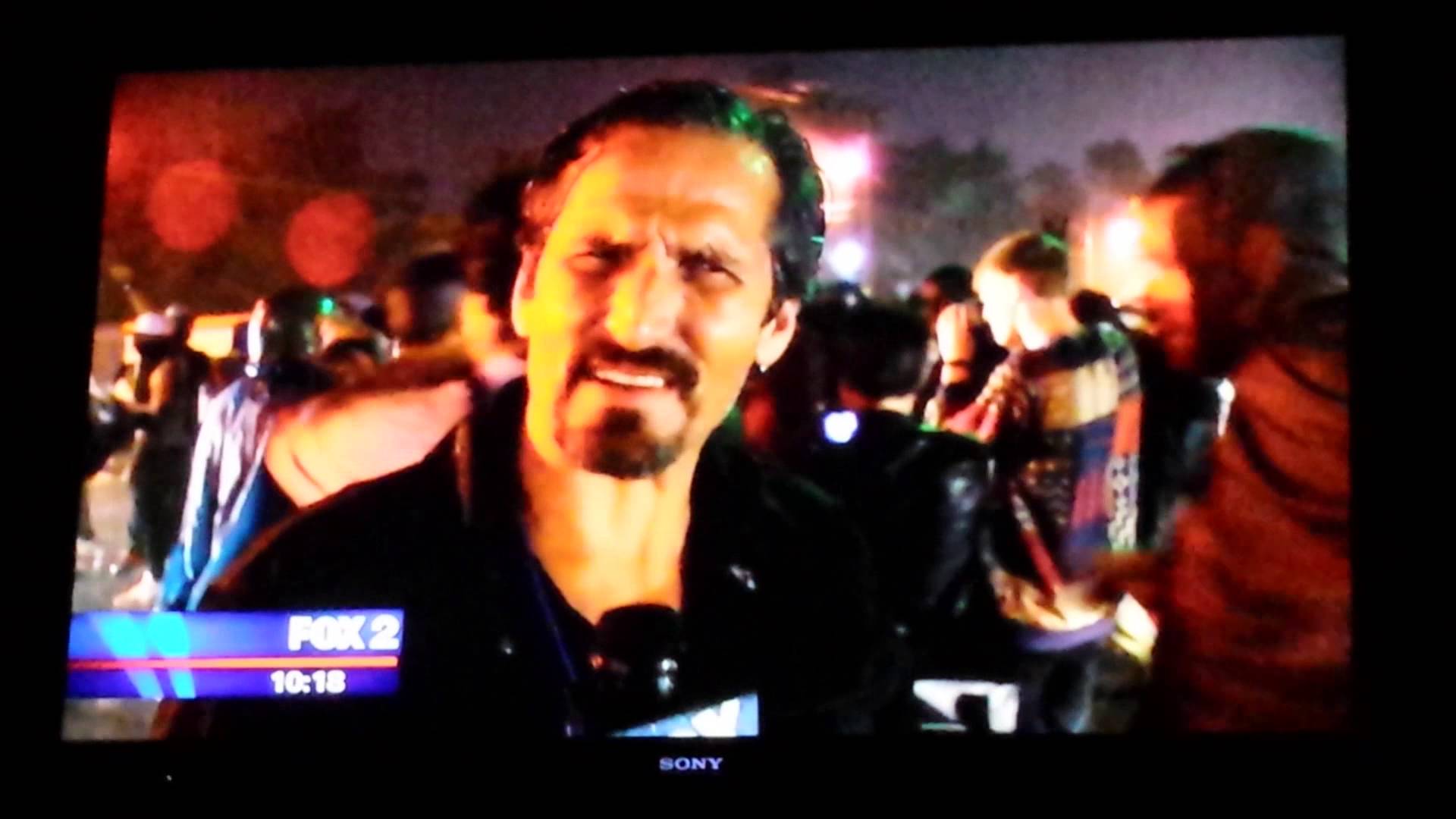

Charlie LeDuff on air on his Fox News show, The Americans, in Ferguson, Missouri. [o]

The last time I sat in the American Coney Island diner with my old compadre Charlie LeDuff, it’s hard to remember precisely what we were doing. Maybe drinking beer—drinking always being on the itinerary during visits, as Charlie believes in upholding the sacred rites of our news-gathering forebears. Or perhaps we were eating Coney dogs, since that’s what people do at Detroit’s premier hot-dog emporium (celebrating over “100 years of awesome,” as the T-shirts say), where proprietary franks are served on homemade steamer buns with chili-mustard-onions—always in that order, a sacrosanct chilidog liturgy.

What I do remember is that it was 2008, and things were different. Back then, Charlie used to hold court at the Coney, filming an online show for the Detroit News called “Hold the Onions.” Now, at age 52, he is more likely to be asked to hold the onions himself, as he’s working here. Not as a journalist, but as an employee: vacuuming the chessboard floor, shining the faux brass, doing the books, swabbing grease fryers. But I’m getting ahead . . .

A decade ago, I was here to write an elegy for dying Detroit. (Spoiler alert: It’s still alive.) I hung with demoralized firemen who’d just lost a buddy under a collapsed roof in the arson capital of the country. They complained of ladders being stolen off their trucks, food being stolen off the firehouse table while they were out on calls—one even lamented that his car was stolen at their fallen comrade’s wake. I went to Motown’s old studio with soul legend and city councilwoman Martha Reeves, who told me of the time a mugger swiped her purse and dragged her 500 yards when she couldn’t free her hand from the strap. I met a homeless gravedigger peddling used clothes in the street. He deliberately slept under a bridge with lots of traffic, so he wouldn’t get thrown off an overpass, as he’d been a few months prior.

Foreclosed, burnt, and abandoned houses were everywhere — hurting a guy’s eyes who grew up in a working-class neighborhood . . .

It was the usual Detroit joyride.

I saw the city through the prism of its bard, Charlie LeDuff, who after a decade-long run as a feature writer for the New York Times (he won a Pulitzer for a month-long stint working the swine-chopping line at a North Carolina slaughterhouse) had willingly punched out of the majors and headed back to the minors, returning to his hometown to work as a metro reporter for the ever-thinner Detroit News.

At the Times, Charlie’s beat had been covering what he called “the Hole,” overlooked people in forgotten places. He’d manned the lobster shift at a Burger King and got himself smuggled over the border with Mexican migrants. While readers scarfed down his copy, editors blanched. One told him it was problematic that all he seemed to cover were “losers.” Charlie figured he was in good company. Having long ago anticipated the problems that the 2008 crash, the dissipating middle class, and the Trumpian middle-finger-to-the-establishment would eventually make clear to the rest of us, Charlie knew he wasn’t some deranged Cassandra, but more attuned to the news than his editors. He told his boss: “The country’s 80 percent losers, and growing every day.” With that, he turned in his walking papers and went home. In Detroit, nobody begrudged his documenting the wreckage, since wreckage seemed to be mostly what was left. As firefighter Mike Nevin, one of Charlie’s recurring subjects, told me of the place that was once the incubator of working-class stability: “Hear the sirens? That’s all day long. This is a city where the sirens never stop. It’s like a forgotten secret. It’s like a lost city.”

Charlie sat in a broken chair in a half-empty newsroom depopulated by layoffs. But as the Lost City correspondent, he wrote like he was avenging a death. In a way, he was. It seemed like everyone he knew was falling into the Hole. The auto jobs had left town for the suburbs or Mexico. Foreclosed, burnt, and abandoned houses were everywhere—hurting a guy’s eyes who grew up in a working-class neighborhood, the son of a flower-shop-owning mom who sported a raccoon coat. One of Charlie’s brothers worked for a crack dealer named Death Cat. His sister had become a part-time hooker and died throwing herself from some crazy’s car. His niece died of a heroin overdose shortly thereafter.

Charlie LeDuff cleaning grease at the Coney Island, Detroit, Michigan. Photo credit: Matt Labash / The Weekly Standard.

He took it all out on corrupt public “servants,” of which Detroit’s always had a parodic surfeit. (One city councilwoman demanded 17 pounds of sausage as part of her bribe.) He wrote of “dead flight,” the living exhuming their dead to take them to the suburbs, where the cemeteries were safer. He found a body at the bottom of an elevator shaft in an abandoned building, frozen in ice, as ruin-crashers played pickup hockey nearby. The man had been there for weeks, his legs jutting out like popsicle sticks. Charlie wrote an acclaimed, bestselling book, Detroit, An American Autopsy (2013). GQ named him “Madman of the Year.” He remade himself as a TV star, first for the local Fox affiliate, then roaming the country. He pumped out one-of-a-kind pieces of frenetic performance art under the title The Americans, which were syndicated to Fox stations across the nation, many of them becoming viral-video sensations. He might eat cat food on air to show how disgraceful Detroit’s meals-on-wheels program had become — the city was procuring grub from a prison contractor. He’d squat in a squatter’s house or take a bath in someone else’s while waiting for the cops to take their sweet old time after the resident called the police. He’d hit a golf ball all the way across the Detroit badlands, one drive after another, to illustrate the sprawling emptiness, and talk to all those living between its cracks.

He also blanketed the country, riding with the Klan in South Carolina and Bundy militiamen in Nevada, paddling around the Rio Grande in a blow-up kayak wearing a stars’n’stripes banana-hammock to catch the attention of the coyotes transporting migrants to the promised land on jet skis, virtually unmolested. He was still minding the Hole. People used to dismiss or ignore it, but now even the pointy-heads and professional gasbags were declaring that more of us were falling into it, as the middle-class was no longer a majority for the first time in over four decades. Even as big cities grew shiny, happy, and gentrified, urban poverty was ripping into the suburbs like a rock thrown into a pond.

Charlie’s method has always been controlled madness, a method that pays dividends. But the gonzo whirlwind he creates, sucking everyone into his vortex, has always been undergirded by moral seriousness. His writing, executed in the hardboiled style, equal parts noir and working-man snapshots-in-words (think Jim Thompson meets James Agee), connects with people because it bleeds humanity. “I got love for people,” he says without guile, not a pronouncement you hear generally misanthropic reporters make every day. Charlie saw the Hole getting deeper—more and more falling prey to the effects of corporate greed, government neglect, or personal dissolution.

Right after Trump’s election, he swept the family photos off his desk into a box and quit his well-paying TV gig. He cut a pilot for A&E, but the proposed docuseries didn’t get picked up. He drops occasional columns for a local website, Deadline Detroit. Though he left me wondering if he’d fallen into the Hole himself. Several weeks ago we were on the phone, having a vinegar-session on journalists’ favorite subject (how journalism is dying), when he broke the news: “You could always come work with me.”

“Where are you working?” I asked, unclear on his current arrangements.

“At the Coney,” he said, “for about a year now.”

“You’re kidding,” I said. “Is it a stunt?”

“Nope, though that’s what my wife asked,” Charlie said.

“You never told me,” I replied, somewhat hurt.

“You never asked,” he said. “Besides, a man’s got pride.”

And indeed, he does. He’s too proud to wear the paper hat while working at the Coney. Nor will he work the register. “I’m not a greeter,” he says. But otherwise, he’s all-in as handyman and troubleshooter for Grace Keros, the third-generation owner, who regards Charlie not just as an employee but a friend. Even more so since, when he was still a TV reporter, he chased after and took down a thug twice his size who’d boosted Keros’s cellphone.

The salary is paltry, and Charlie mainly took the gig for the health care it offers . . .

Charlie puts in several days a week at the Coney. He putters up early one morning in his matte-black ’77 Cadillac Fleetwood (he likes a car he can work on) wearing motorcycle boots and ancient Carhartt coveralls, splotched and stained and air-conditioned with the ass half-ripped out. He tells me he inherited them from a firefighter when he was covering the Manhattan firehouses after 9/11. I ask the last time he’s washed them. “Gonna be honest with you,” he says, “I never wash them.” Charlie ricochets like a pinball around the Coney, playing off line cooks, many of whom he’s nicknamed. There’s Yoda, so christened for his prodigious ears. They talk everything from local politics to economics. Ali comes by and slaps Charlie five. “He supports a whole village back in Yemen,” Charlie says. Charlie asked Ali one day what his dreams were. Ali told him, “Make a million dollars, nice car, nice house, and maybe get my wife.” “As in, ‘bring her over, maybe,’ ” Charlie clarifies, laughing. “The American Dream is not dead,” I say.

It’s spring cleaning at the Coney, and Charlie needs to clean out the grease behind the fryers before the roaches, now thawed, decide to take up residence. Though the Coney stays open 24/7, early construction crews and last night’s drunks are pretty much the only ones wanting chili dogs this early. It’s a good time to shut the chow line down and let Charlie do his work.

He gets after it, on his knees, with pumice, degreaser, and soap. He takes out mummified hot dogs and fat globules with a Shop-Vac. He scoops large handfuls of sludge out of corners with his bare hands. His arm hair is covered with steel-wool shavings and is slightly singed, from someone leaving a burner on. Maybe it’s just the Tom Sawyer effect, wanting to make others want to paint the fence, but he looks like he’s actually enjoying himself, attacking his task with gusto. Keros tells me he’s a model employee, even if he takes frequent smoke breaks and today knocks off now and then to drink locally brewed Dirty Blondes with me—we professional journalists start early. Keros is kind enough to pour them into Pepsi cups for us.

The salary is paltry, and Charlie mainly took the gig for the health care the Coney offers. His hardship is gentleman’s hardship. His Craftsman house out in Pleasant Ridge by the zoo is paid off. His wife is studying for a PhD in counseling. His daughter goes to parochial school. But when he walked away from his well-compensated TV gig, he lost the family’s insurance and was in for some serious sticker-shock. I ask him why he left TV and get a lot of answers over the course of a couple days. For starters, his Fox superiors pressuring him to lay off Trump and certain local politicians now that everyone’s celebrating the “New Detroit.” Which, as Charlie repeatedly says, “is bullshit.” Sure, downtown looks spiffier than ever with the billions in investment (often attached to sweetheart deals, land swaps, and other breaks financed on the taxpayers’ backs) that poured in. But if you dig, the New Detroit looks a lot like the old one.

Book cover . . . LeDuff describes himself as a “street reporter… The story was and always will be the American people scratching it out from Ferguson to Flint.” [o]

A deputy police chief just went upriver for accepting bribes from towing contractors. She called them “loans.” The feds are quibbling with Detroit’s reporting of its crime statistics, saying it is still the most violent city in America. Murders are at a half-century low, yes, but the population is also at a hundred-year low, meaning there are fewer people left to kill. Despite all the new craft brewers and artisan pickle-makers celebrated by travel writers who parachute in for a couple of days and stay downtown, entire quadrants of the city still look like apocalyptic wastelands. The new mayor, Mike Duggan, is knocking down more abandoned houses than ever, but a federal grand jury has looked into irregularities and kickbacks with the demolition contracts. The corruption drives Charlie so crazy that he often feeds leads to former TV rivals. Half of the candidates in last year’s mayoral primary had felony records. As a cabbie named Junior said to me of the New Detroit, “It’s a cover-up, like making a shitcake and covering it in frosting.” His car was choked with weed smoke, and he winked cartoonishly as he explained that the “medicine” was for his “bad eye.”

Charlie also cites as reasons for checking out of his TV gig things like getting screwed on expenses—having to front the travel costs with his camera crew and then getting nickel-and-dimed by superiors for, say, ordering nine beers while interviewing a Times Square pimp. (“He didn’t want baked ziti, he’s a pimp!” Charlie says.) Finally, he says, sighing, he got tired of the monkey show, the fake news, and how the split screen has multiplied into an octagon-screen of talking heads—“housecats” who never leave the studio. A culture of nothingness pervades TV even when the country is genuinely ailing. But he also admits he just got tired, he tells me one day in his kitchen, drinking black coffee in front of a cabinet upon which are posted the Beatitudes. “Too many bodies,” he says, “too many broken hearts. Old ladies living in their vans because they got put out. People washing their babies in the sinks in Flint. I mean, you know, at some point, it’s just . . .”

He wanted to reassess, put it all in some kind of order. Which he’s done in a new book, appropriately titled Sh*tShow! The Country’s Collapsing . . . and the Ratings Are Great. He sweeps the country, making connections, from black rage in the streets of Ferguson to white rage everywhere else. He hangs with Flint trailer-park denizens, who’ve been left high and dry by the government and the auto plants that turned the city into a ghost town. But he also hangs with Mexicans on the other side of the border, where the auto plants went—where they work for pennies on the dollar and yearn to ride coyote jet skis across the Rio Grande to try to get a piece of the American Dream, which so many Americans assume has fled south. The book is riveting and an important document of our time.

Charlie admits he misses the life: “I miss it all. I miss shitty airports. I miss country roads. I miss Baton Rouge at midnight, the only thing open is that fish-fry-liquor store. I miss the action. I miss saying something. I miss the bullhorn. It’s the best job ever invented.” But he’s okay sitting back, reassessing. Figuring out what’s next. Meanwhile he has work to do at the Coney, making Keros happy, as it means his daughter has health care.

A fan recognizes Charlie LeDuff working at American Coney Island. Photo credit: Matt Labash / The Weekly Standard.

He flirts with a large black woman with a crooked weave, who comes in and recognizes him from TV, as so many customers do. She squeals “Charlie! Charlie! Charlie!” even as she wonders what the hell he’s doing here. “Working!” he says without shame. She says she’s just come into a $4.2 million civil judgment, since Shower to Shower talcum powder killed her mother. A sprinkle a day apparently helped keep the odor away, but also “gave her ovarian cancer.” Charlie throws his arm around her: “I’ll be your sugar daddy.”

He has to throw the Pigeon Lady out of the bathroom. MISS QUEEN—as she calls herself, insisting on all capital letters—is a regular who likes to bring in her pigeons and bathe in the restroom sink. “I’m the only QUEEN on planet earth,” she explains to me while getting bounced. “I’m an angel, an alien from heaven. In this world, not of it. Don’t give a f— if He blew this whole planet up.”

Charlie has to greet George the Greek, an elderly gent he once wrote about while at the Detroit News. After George’s wife passed away, he became “the patron saint of lower Woodward,” living in a grand old abandoned bank to guard it from looters.

And then there’s the African-American couple in head-to-toe purple who forgot their teeth while eating their Coney dogs. Charlie chases down the street after them with their partial bridges in a to-go container. “You forgot your teeth!” he yells. The couple collectively says “Ohh!!” then start feeling their gums, wondering who forgot their teeth. “Both of them!” they concur, though without their teeth, it sounds like “Bof of vem.” Charlie hands over the styrofoam hot-dog case with their choppers in it. “Served fresh and hot,” he says with a smile. They are extremely grateful. The woman tries to hand Charlie a $10 tip. He refuses. All in a day’s work. The good people of Detroit should not be walking around toothless.

If this seems beneath a Pulitzer-winner, Charlie doesn’t think so. “It’s okay,” he tells me. He’ll be back. In fact, he never really left. He has a book about to do its work. A lot of reporters go whole lifetimes without writing a book, since they have nothing to say. He’ll figure out his next move. Until then, the Coney suits him. “It’s honest. It’s fun. It’s cool.”

When you’re done, you’re done. You punch out, and can see your handiwork—something is clean. Also, he says, it’s good for him personally. In TV, you can start to think you matter more than you do. But we’re all in it together. We all live with the same struggles and fears and uncertainties. “Humble yourself,” Charlie says. “I got a little bit tired of it. I’m redoing my life. A little bit of real people doesn’t hurt. A little bit of real life doesn’t hurt. Be on your knees, scrape some dirt. Love the other. Try to dig people. Whether you have God or not, God told you to focus on life on earth, and if you do, there’s a place for you in heaven. This is longstanding wisdom from our elders. Take this as wisdom. Take it.” ≈©

Charlie LeDuff had history with American Coney Island before he got a job there. [o]

MATT LABASH is a senior writer at The Weekly Standard. His collection Fly Fishing with Darth Vader: And Other Adventures with Evangelical Wrestlers, Political Hitmen, and Jewish Cowboyswas published by Simon and Schuster in 2010. "Labash specializes in long-form, humorous reportage. Many of his pieces are profiles, often of crooked and disgraced politicians; others are accounts of offbeat conferences or portraits of cities on the skids, such as Detroit and New Orleans." [Wikipedia>] He lives in Owings, Maryland.

Comments

Great story. Charlie LeDuff

Great story. Charlie LeDuff has the right stuff.

Add new comment