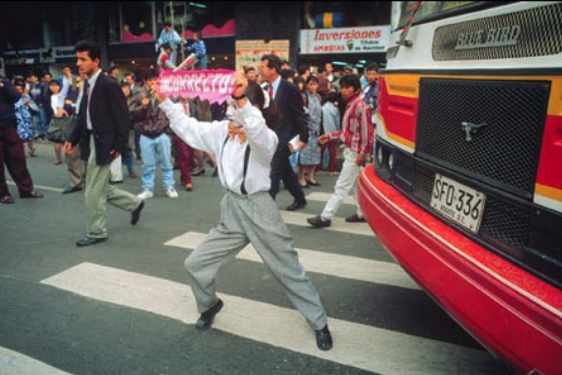

"A very wide variety of people gather to form the group Possible Mexicos, working to reach agreement on "what our Mexico could be." [o]

1. SEEING PROBLEMS FROM ANOTHER ANGLE

WHITNEY SMITH: In recent years Mexico has had what some might think is an apparently insurmountable or intractable problem, at least as viewed from outside the country, somewhat to do with violence, but many other issues as well. As you are now working in Mexico, can you tell us what you are bringing to this process to help find some success?

ADAM KAHANE: Well, first of all, I don't really know what intractable means. My early training was as a physicist, as a natural scientist, so it took me a long time in my current work — which is working with people and human systems — to realize what everybody else already knew: that things are not so straightforward in human systems as they are in physical systems. So let me say, I don't know how to figure out objectively whether something is intractable or not.

I used to work for Shell, in the late 80s and early 90s, where I was in the Scenario Department, and my main teacher there, my boss, was a man named Kees van der Heijden who later wrote a important textbook on scenario thinking. He was the person who taught me that the correct word to apply to such situations is not problem but problematic situation: because it's not anything as straightforward as a problem that has a solution, it's a situation which is problematic, in part because different people view it as problematic from different perspectives and for different reasons. So yes, for many people, certain aspects of the Mexican reality are problematic, and that aspect of the Mexican reality has prominence inside Mexico, but maybe even more so outside Mexico. So it took me quite a few years — and I'm a bit slow on the uptake — to realize how much there was that was wonderful and not only problematic.

It brings together actors from across a whole system to meet and talk and act together.

That said, yes, my colleagues and I from Reos Partners and I have been working for four years quite intensively in Mexico with a project called Méxicos Posibles — Possible Mexicos. I'm very happy with that title because what's important about working on social systems, and working on the future, is that there's more than one possibility. There's possibilities and they're plural, so Possible Mexico is with an 's' — to me that means a lot. When we first started four years ago, it was right after we were first contacted after the massacre in Ayotzinapa, which was chronologically around the same time as there was a lot of controversy about President Peña Nieto's house. [A 2014, an article was published about a $7 million "White House”, owned by President Enrique Peña Nieto and his wife, that was registered under the name of a company affiliated with a business group that had received government contracts.]

SMITH: Who contacted you to work on this project?

KAHANE: We were contacted by a small group of business people, public intellectuals and activists from Mexico who had heard about the work that we’d done in Colombia, and before that in South Africa. It was not a formal group, and — this is the key thing — they did not all necessarily agree on a lot of things; however, they did agreed that the current reality of Mexico was problematic. We started off by going for a week to talk to these people and in a few days we ended up talking with 160 people, so it was a bit ridiculous. Anyhow, we had lots of meetings, including a few very big ones, and the way we made sense of the interviews was that there was a set of concerns that could be summarized by the words insecurity, illegality, and inequity. We could think of a lot of other words that start with ‘in’ that we could add to those three — impunity, for instance — but it seemed that those three words would summarize it. The importance of those three words was not that they were in any way exhaustive, but that they signalled that the problematic situation was multidimensional — rather than saying it's all about X.

For example, in the initial framing, people were saying it's all about the rule of law — and maybe that's an apt summary, maybe it's not. But I thought that to signal that it was multidimensional — or to connote that it was multidimensional — and to talk about possible futures was something useful. And the other conclusion was that there were certainly a lot of people concerned about the problematic situation, but that there weren’t adequate fora or spaces for people from across the system to work on it together.

So Méxicos Posibles has become — and it's now been going strong for four years — a group of about a hundred people from all walks of life in Mexico. And its most extraordinary feature is that it brings together formal and informal leaders from all parts of Mexico, or as people say, from the many Mexicos — indigenous leaders, police and army and navy officials, people from the presidency, CEOs of international and national companies, academics, intellectuals, politicians from all parties, human rights activists, journalists — all who share a concern about the problematic situation and think that they could do more about it together than they could separately.

One of the spin-off projects, or let's say daughter projects, is a new initiative called the Mexican Education Lab — a mostly new team focused on questions of education. So the short answer to the question you asked is the work I've been doing for the past 27 years, and the work we're doing in Mexico, has as its most important feature that it brings together actors from across a whole system, in this case, the Mexican system, or the Mexican education system, to meet and talk and act together.

Possible Mexicos: "What would Mexico be like if we were to see that we can build a desirable country for the vast majority, even if we think differently?" [o]

2. BUILDING STRUCTURE FOR CREATIVITY

BEATRICE BRIGGS: I would love to hear more about what you do when you get the whole system together to meet and talk. What is the format or process that goes on?

KAHANE: We have had 10 meetings in the last four years, with a group of 40, 50, 60 people at a time — usually the same people, but with multiple generations of these groups. We're now in the third generation of the original group, and it’s meeting multiple times. The conversation is about what's going on and what can we do about the situation we have come to address. Or, to be a little more precise — what is going on, what could go on, and what could we do about it.

This is work which, on the one hand, is highly structured, and on the other hand is completely open or creative. For example, of the little bit I know about jazz, the structure is tightly constrained: certain melodies, chords and number of bars, while within those structures there's a lot of room for improvisation and creativity.

So the workshops are very structured, and I'll give you one example. Though it might seem trivial, to me it isn’t. The very first thing in a group coming together is for people to introduce themselves. In a group of 50 people, that can be quite a long process, and in some cultures it would be a long or very hierarchical process. So what we have been doing — which doesn't work everywhere but has been important and successful in Mexico — is to give everybody one minute to introduce themselves, which is short enough that you can pay attention. It's interesting if you ask the right question, which is maybe not “Give us your bio,” but “Why are you here?” What's more important is that everybody has a minute, that the minister has a minute, the young person and the indigenous peasant and the academic with four PhDs has a minute. In very formal and hierarchical social systems, this is a shocking way to start. I would say it doesn't work in all cultures, and I have recent experience of it not working at all, but it has worked very well in Mexico.

Scenarios are, by definition, multiple stories about what could happen, not what should happen, not what will happen, but what could happen.

So that's an example of a rigid structure, but within which you can use your minute to say whatever you want. Another thing we’ve done at the beginning of these groups is to ask people to bring with them a physical object that represents, for them, the current reality. Instead of introducing themselves, they take a minute to say what the object is and why they brought it. It's very interesting to have people say what they think, not with a speech or with a slide presentation or with a polemic, but with an object. First, it forces people to be metaphorical, and second, all of the objects can be displayed on a table in the middle of the group. I use these objects as examples of what it means to work in a way which is both very structured, minute by minute, and entirely open — where we as the facilitators provide zero guidance as to the content, but are very tight guidance as to the process.

So that's an introduction to answer your question about format and process, which is that in Méxicos Posibles the first two years were on the question, “What is going on and what could go on?,” and the method for that is the scenario method. Scenarios are, by definition, multiple stories about what could happen, not what should happen, not what will happen, but what could happen. And you'll find on the mexicosposibles.mx website four very interesting scenarios, which are provocative statements about what is possible, good and bad, in Mexico, including some aspects that everybody in the group considered ones to be avoided. So that's what we've done before we started the education work.

3. ASSUMING WE KNOW WHAT IS VS. PRAGMATIC ORIENTATION

SMITH: One example of a problematic situation in Mexico, one that has attracted international attention, is the issue of violence and the role of the drug culture. Can you comment on that, in terms of how we might understand the work you’re doing in that country?

KAHANE: Here's an indirect way to answer your question. I first went to South Africa in September 1991 and had my first experience of what we'd now call multi-stakeholder or multi-sector dialogue work there, with a process called the Mont Fleur scenario exercise. I ended up emigrating there in 1993 and marrying the project organizer — the usual story — and I've spent the last 25 years moving between there and Canada. Most well-informed people know a little bit about South Africa, and people often say to me, “Oh, well, that was pretty simple — it was just the Blacks versus the Whites.” And of course, for those of us who know more about South Africa, know that — though, yes, that was an important part of the story — it was by no means the whole story. It wasn't the whole story then, and it's not the whole story now.

"Zero guidance as to the content, but very tight guidance as to the process." [o]

So I would just say that people who don't know much about Mexico would say, “Oh well, I saw the TV series Narcos. This is just about the drug trade or the immigrants . . .”, and I would say the same thing I'd say to people in South Africa: “Yes, that's part of the picture, an important part of the picture — I'm not saying it's not — but it's an impoverished summary.” That was what we were signalling by talking about illegality, insecurity, and inequity. And I say signal because it's just three words, and could have been another three words. But we're saying, yes, illegal activity, drugs, US demand for drugs, rule of law, political history, corruption, inequality, oppression, marginalization — these are all part of the story. By the way, while I'm not accepting that framing, my answer is more by disposition than by analysis.

SMITH: Absolutely. I say that partly because when I invite people to come down to Mexico, and they say, “Oh, Mexico, how wonderful,” while often you know they're thinking, "Ah, Mexico, danger."

BRIGGS: I lived in Chicago for 20 years, which is a Great Lake City not unlike Toronto, but it has a lot of violence and social problems. It’s not like there's blood on every street, every day, and the same thing is true here in Mexico. Most people just live their lives, while avoiding certain places at certain times. It's not to deny the reality of the cartels and the issues that it causes, but, as you say, it's not the whole story.

KAHANE: Here's maybe another way to answer your question. For me, my orientation is — just by personality — a pragmatic orientation. What interests me is how can we deal with the situations we find ourselves in. And people who don't understand a system will come up with very inadequate answers to that question. An example of this is: I don't know much about corruption as a phenomenon; I'm not a specialist at all in that area. And I once had a meeting with the head of the Indonesian Anti-Corruption Authority who apparently was a very well-respected and competent person. I said, “Oh, corruption . . . isn't that a purely judicial or law enforcement matter?" To me in my ignorance this seemed pretty simple: “Why don't you just lock up the people who are doing bad things?” And he answered, as somebody who knew a lot about this, "No, it's really not like that. It’s about lots of things. It's about culture and political campaign financing and who trusts whom — and lots of things."

BRIGGS: And economic access . . .

KAHANE: . . . and civil servant pay scales, and international organized crime — lots of things. So when I asked him, his answer to me was, "It's not as simple as you think it is." To cut to the chase, the pragmatic answer to the question — “How to address the Mexican reality?” — is: let's get a group that is able to understand the complexity of the situation. There's a phrase in this kind of work that talks about requisite complexity. What is the kind of work or kind of group that's able to deal with a given problematic situation? It's stunning to me, and rewarding, but also breathtaking, how — when a group like Méxicos Posibles comes together for the first time — probably a 100% of the people walking in the room think that they pretty well know what needs to be done. “If only these other people would listen to us, we'd be fine.” Then they gradually realize that that's not true, that there's a lot more to what's going on than each of them realize. And what's even more interesting, which relates to my disability in these groups since my Spanish is not very good and work through interpreters all the time, is that one of the unfortunate consequences of this is that I tend socially to speak to the people who speak good English, which, with some exceptions, tends to be the elite. So in the Méxicos Posibles group, in general (there are some exceptions), the people I chitchat with and have the most open conversations with are the elite in the group — perhaps a quarter or a fifth of the group: the economic elite, the business people, the professors, and the people who've studied in the United States, and so on. And what I've noticed in Mexico, like in other places, is these are the people who get the big surprises. They’re the ones who are walking around with their jaws on the floor because they are seeing only part of their reality — part of the reality that was invisible to them.

"We must let go of the life we have planned so as to accept the one that is waiting for us." — Joseph Campbell. One of Kahane’s main teachers edited Campbell’s ‘The Power of Myth’. [o]

So this is a very interesting thing about life — that the way things really work is more obvious to people from below than from above. Therefore, the requisite diversity of the group in understanding the problematic situation is greatly enriched by the so-called ordinary people who are members of the team.

SMITH: Adam, can you just speak about the value of the so-called experts and the actors on the ground floor — the academics and think-tank professionals versus the community actors?

KAHANE: The answer to that question for me is quite clear. With a pragmatic orientation, the people who are most important to have in the room are the actors — the action-oriented activist actors, as I call them. And by the way, for many years it’s been a big riddle for me that people in this kind of work would often say, "Well, how do you get people to act?" And I realized it's a nonsense question (as most questions are nonsense questions) because actors are acting all the time, that's what they do — they get up, they act until they go to sleep. And so the question is not, “How to get people to act?”, the question is “How can people act with a greater sense of the whole and a greater sense of connection to each other?” To answer your question, in any kind of social system there are many different actors. On questions, for example, of illegality, insecurity, and inequity, there are armed forces actors, political actors, economic actors, NGO actors, journalism actors, and so on. The experts who can inform them are easy to get. There’s a line in my favourite movie, The Big Lebowski, where one of the characters says, “I can get you three of these before 4:00 this afternoon.” Of course it's very helpful to have experts, or as we call them, ‘resource persons’ — and the renaming is important because experts are people who tell you what they think you need to know and resource persons are people who help you figure out what you're trying to know. So there's a role for resource persons in these processes, but it's not the hard part. The hard part is for actors to connect to each other, and to improve the quality of the alignment and connection of their actions.

4. FISHING FOR A NEW STORY

BRIGGS: Reading some of the articles and interviews you've done in the past, I was fascinated by your references to the story and the stories we tell, and the need for a new story. My interest in this is partly influenced by the work of Thomas Berry, a theologian and cultural historian who died a few years ago who also talked about the need for the new story. What would it take to bring in a story that people were actually acting on?

KAHANE: I have a friend who's thought about that a lot and is very wise about it, a great teacher of mine, a woman named Betty Sue Flowers, an amazing woman who was for many years a poetry professor at University of Texas at Austin, now living in New York City. She became very famous because she was Bill Moyers' editor for a long time, and in particular the editor of The Power of Myth, his book with Joseph Campbell, and she was very interested in stories and myths. When I was at Shell in 1988, she had been hired to edit the Shell Scenario Report, an annual or semiannual publication, and has been doing it ever since. I asked her why it’s of interest to her to spend a few months a year working for Shell, and she said that a part of her life work was related to the new story. She would have a more developed perspective on it, but I have a sort of simple perspective on it, which is that the stories that we tell about what's going on in the world really matter — those things we pay attention to, and what we think is important.

Adam Kahane. [o]

To stay with the Mexico example: the stories Mexicans tell about what is happening, what could happen, and what should happen — even though you might say it doesn't matter at all, or it's the most important thing of all — that Is what Mexicos Posibles has done. And what Betty Sue Flowers would say is: myths and stories are a big part of how people understand and understand the world around them. So for me that's one aspect of how story is committed. The point I make in my book Transformative Scenario Planning, the difference between the way we did scenario planning in Shell (which I call ‘adaptive scenario planning’) and the way we did scenarios starting at Mont Fleur in South Africa and all the way through to Méxicos Posibles is the people at Shell were telling stories about what could happen so as to be able to adapt and survive, no matter what happens — a perfectly reasonable thing to do. But South Africans and the Mexicans and the other groups I've worked with in between, their stories are about what might happen so as to influence the future. One of the reasons the future is unpredictable is because it's influenceable, and the people who are involved in Méxicos Posibles are — I wouldn't say they’re in control of the country — but together they are quite an influential force.

And so this is telling stories in order to understand and shift the future. So that's one whole thing about stories. The other aspect is that for any highly diverse group which comes together, in many cases, not agreeing with or liking or trusting each other, the question about how to connect with one another is very important. So stories is the best way of connecting, and many of the stories in my books relate to this telling our own stories. And in the place we’ve been meeting in Cuernavaca, Misión del Sol, there is a small round room there called the oratorio. I actually don't know what it was built for, it’s pretty small, but Méxicos Posibles uses that room for storytelling evenings.

BRIGGS: It sounds like it could be a sweat lodge. Though 50 people wouldn't fit in the sweat lodge, it's probably that same type of space?

KAHANE: It is that shape, but I don't think it's a sweat lodge and I don't know what it was built for, but for every meeting we've had there, we use it for storytelling. It is one of the most impactful structures for that. We say, “Let’s spend an hour before dinner with a glass of wine where people who want to are invited to tell stories — anything from their personal life that they think is relevant to what we're talking about here.” And doing that is amazing and very impactful structure as well. Carl Rogers said what is most personal is most universal, and I think the transition in this group from being people who don't agree with or like or trust each other to people who — though they may still not agree with each other — like each other and trust each other and are able to work together. In no small part does this relate to the storytelling.

SMITH: Is there an example of a situation with a group where you went in and things weren't working, where there was no cohesion or productivity in the group, however, through your work with the group a new story came up and embodied some sort of progress.

KAHANE: One of the most interesting projects or efforts that I've been involved in, partly because it's gone on for so long, is my work in the country of Colombia. I started work there in 1996 with an out-of-work politician, Juan Manuel Santos, who several decades later became President, then won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016, and is now the former president. But the project that he and I were involved in, in ’96-'97, was a scenario project — and so there was storytelling. It was a very remarkable group because it included all the factions in the Colombian conflict, including the left-wing guerrilla groups, the FARC, the ELN, the right-wing so-called self-defence forces, government people and church people, trade unions, community groups, businesspeople, and so on. And they came up with a set of stories about what could happen in Colombia.

Santos and Londono sign the revised agreement, Nov. 29–30, 2016. The Colombian armed conflict is the oldest ongoing armed conflict in the Americas, beginning, by some measures, in 1964. [o]

It was remarkable just because the group was in this tiny hotel in the middle of the countryside where people were literally slaughtering each other outside the workshop. There had to be a ground-rule, which was set up at the first workshop. “Nobody would be killed for any reason,” they said, “in the meeting.”

It was a very dramatic event, yet through some strange coincidence or synchronicity, the four Colombia stories became very, very well-known, and have unfolded in Colombia more or less in the order they were written. It's become a bit of a bizarre thing amongst at least that generation of Colombian opinion formers — why or how did Destino Colombia [Destination Colombia] become, how did it become not only a scenario process but a prophecy? That's the word Santos uses. “It was prophetic,” he said, “it wasn't academic. It was prophetic.” Because you can make a very convincing argument that the four scenarios have unfolded in the order they were written. That's to say: tomorrow will come as we'll see, then the bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, then everybody march, and then in unity is strength. At least that was Santos's story, that he was enacting the fourth scenario, that his government was enacting the fourth scenario. So at least during the period from 1996 to 2016, it follows that sequence.

I once had a conversation with a man, a very amazing Colombian politician, intellectual and mathematics professor named Antanas Mockus. He was twice the mayor of Bogota, a very charismatic and very, very unusual and brilliant social sculptor who did things in Bogota that nobody had ever thought of doing. The famous story about Mockus is that there was a very high rate of vehicular homicide in Bogota and you couldn't address it by fining people because it was sort of a macho thing to do. So he hired a hundred mimes to stand on street corners and make fun of people who were driving badly, and the embarrassment factor brought down the rate.

Mockus is a legendary figure globally in creative, artistic ways of changing social systems. He's a genius. I once had lunch with him and he said, "Adam, we've gone through the first three scenarios, but I want to know how to get to the fourth scenario. In the report it seems to be missing a page, it doesn't explain how you get from the third to the fourth." I said, "Antanas, these are just stories from a workshop, it's not a recipe book.” “You're kidding, right?" he said, "No, no, seriously. What is the missing page?" So anyhow, it's the best story I know about how a set of stories became part of the national understanding about where we've been and where are we going.

BRIGGS: When we’re looking at such complex issues there’s something so humanizing about the idea of story being so important.

KAHANE: Yes. In Transformative Scenario Planning I tell the Colombia story and this point is made with a lot more detail.

Fighting vehicular homicide in Bogata. ‘When there is nothing to be done, it’s time to bring out the clowns.’ [o]

SMITH: We've talked about high level problematic situations, in Mexico, Colombia and South Africa, and Shell’s work with scenarios. To what degree might these processes be applied to everyday life, to citizens facing problematic situations, whether it be with their families, neighbours or local organizations they’re involved with?

KAHANE: I have a publisher in Japan who I like a lot, and he sat me down after my third book and said, “Adam, I really wish you would write a book that would be of interest to more than a hundred people. Could you please try harder, because sales are . . ." I took that seriously and worked really hard with some success in my last book, Collaborating with the Enemy, to write a book that was more generally useful. And the argument I make in the book is that these dynamics I’ve had the privilege of being able to observe — in dramatic settings and in bright colours — are identical to the dynamics in more ordinary situations; it's just that in more ordinary situations they are more muted, and so harder to see, and also, they're more normalized. There's a wonderful quote by Alain de Botton in his novel, The Course in Love, where he says something to the effect that, "People spend so much time on problems of astronomy and cancer research and the same things are also present in everyday life." He said it much more beautifully than I have. So that's the point I make in my most recent book, and in all of the articles I've been writing in strategy and business is that, as far as I'm concerned, it's all the same stuff, whether it's in Colombia with the guerillas, or the local community organization, or me and my wife, or amongst my colleagues, — all the same stuff. Literally all the same stuff.

And the underlying thing is — at least one aspect of it — that I'm trying to be something in the world: I have an ego, I have identity, ambition, thoughts, feelings, and so does everybody else. So we bump up against each other as we make our way forward in that world so covered up by defensiveness and pushiness and misunderstandings, all day every day, as far as I'm concerned.

SMITH: As a parent has expectations of their child, and how those expectations butt up against reality.

KAHANE: In Collaborating with the Enemy I talk about three stretches, and the third stretch for me is the most profound. It starts from the observation that when people say for the system to change, people need to change what they're doing, they almost always mean other people need to change what they're doing. It's soothing to think about what other people ought to be doing, and in another way it's a complete waste of time. But what matters, in the end, is only what am I going to do next. So the third stretch is to say, no, I'm a player in this situation. What am I going to do next? I will not fall into the temptation of, if only those drug lords wouldn't do what they're doing, if only those corrupt politicians, if only Trump, if only my kids, and if only this, if only that. Quite a waste of time.

SMITH: So Adam, have you received a call from Venezuela yet?

It's not a criticism. Some people learn from books and some people learn in other ways.

KAHANE: I’ve been trying for about 15 years to work in Venezuela without success, and I don't think I have anything particular to contribute there now. There’s always four ways to deal with a problematic situation, and for many people the default mode is forcing: “Let's try to make it the way I want it to be.” And I think that's been the default mode in many places, contexts, and relationships, and it's been the default mode in Venezuela — and I think it still is.

SMITH: Is there any quick advice you could give to those players, those actors?

KAHANE: No, there's no quick advice that's ever useful.

BRIGGS: To finish, let’s return to where we began, with your background and seminal influences. Is it possible to trace, for yourself, an intellectual tree that brought you to be able to make the contribution you've made, a tree that is still growing?

KAHANE: Let me give you two answers which I think are probably both different from what you're expecting. My first book was called Solving Tough Problems, and Peter Senge, who's an acquaintance and someone I also worked with, kindly wrote the foreword. When we were talking about it — and obviously he had the manuscript of the book — he said, “There's not very many footnotes here.” And I started to apologize. He said, “No, no, it's not a criticism. It’s just some people learn from books and some people learn in other ways.” I'm definitely somebody who learns in other ways. Everything I've learned has been through experience and generally through a very particular type of experience; thinking I knew how things were, acting on the basis of how I thought things were, and running into a brick wall and falling down and wondering what just happened there. So about 90% of my most learningful episodes, which include up to the present month, have to do with things not being as I want them to be, as I thought they were, wondering what's going on here that I don't know — so I scratch around to discover. It was Betty Sue Flowers who suggested that form to me. She said, "Adam, here's a good form for you, tell a story and then interpret your story, like in the Talmud." Anyhow, all my books and articles have exactly that structure, which may be even a little tedious by now for the reader.

BRIGGS: Or maybe not.

Columbia's congress at the July 20, 2018 swearing in ceremony, which included former members of the FARC, given ten seats as part of the 2016 peace process. [o]

KAHANE: [smiles] Another way I’d answer your question is through this. After Colombia I worked a lot in Guatemala, and I have a friend there who was an academic and economist, and he went to work for the Jesuit University in Guatemala City. He had never worked with Jesuits before and they have a very particular way of running things. What he said, which made a deep impression on me, was that Jesuits are very big on gifts. And for Jesuits, the big thing about gifts is, when you have a gift, is that it's not something to be proud of, because, by definition, it was given to you. The really serious thing is about using your gifts. I found this such an interesting idea. And so, my version of that is, I have a gift. I know where I got it. I got it from my father or my parents — a gift for being clear, for listening well, for being self-reflective, for being calm and grounded. And it's not something to be proud of. I didn't make it, I got it. It was given to me. But the thing is, why that story from Guatemala was so liberating for me is I realize the thing to do is to use it. The worst thing you can do with a gift is hide it, hide your light under a bushel. So I have certain gifts which, in South Africa in 1991 when I was 30 years old, I was lucky enough to discover. I guess a lot of people discover their gifts later in life, so I consider myself very privileged. I’ve still had to learn a lot of things and make a lot of mistakes. I could count on one hand the number of intellectual influences I’ve had — I consider them a very unimportant part of the story. I like buying books, but I don't read them much. But I have a lot of bookshelves. ≈ç

WHITNEY SMITH is the Publisher and Editor of The Journal of Wild Culture.

BEATRICE BRIGGS is the founder and Director of the International Institute for Facilitation and Change (IIFAC), a consulting firm based in Mexico. She works in both English and Spanish with clients that include civil society organizations, government agencies, international non-governmental organizations, and private-sector companies. Her publications include Introduction to Consensus, The Bonfire Collection: A Complete Resource Guide to Facilitation and Change, No More Boring Meetings! and Coffee Break, a monthly blog. Born in the US, Beatrice lives in the mountains of central Mexico outside the town of Tepoztlan. View Bea’s website www.iifac.org

ADAM KAHANE is at @adamkahane and www.adamkahane.com

Comments

A really worthwhile read and

A really worthwhile read, and deeply instructive. Thanks for tracking this actor! Right now I am tested by some community groups with whom I work as an actionist / researcher around issues to do with eco-social design and regenerative agriculture who have a strong default tendency to assume that there are 'experts' who know how to solve local problems (not how to describe the complexities of the problem situations) that they can call on, thereby avoiding the need to explore the complexity. ¶ I think of this tendency as some kind of 'internalized oppression' that has people of low status (farmers, field workers, tradespeople and the like) repeatedly disempowering themselves by deferring to these 'experts'. ¶ Meanwhile, the 'experts' play their part in this dynamic by insisting on being the 'experts' — as this is usually the way these people maintain their status and make money. ¶ I can see that Adam Kahane's 'rigid structures' (liberating structures?) — such as limiting introductions of meeting participants to one minute — would help a lot with this. And, I'd love to see a conscious dynamic develop in which people holding the 'internalized oppressions' get to uncover these and delimit themselves, whilst the so-called experts actively learn how to become resource allies to the community at large.

Add new comment