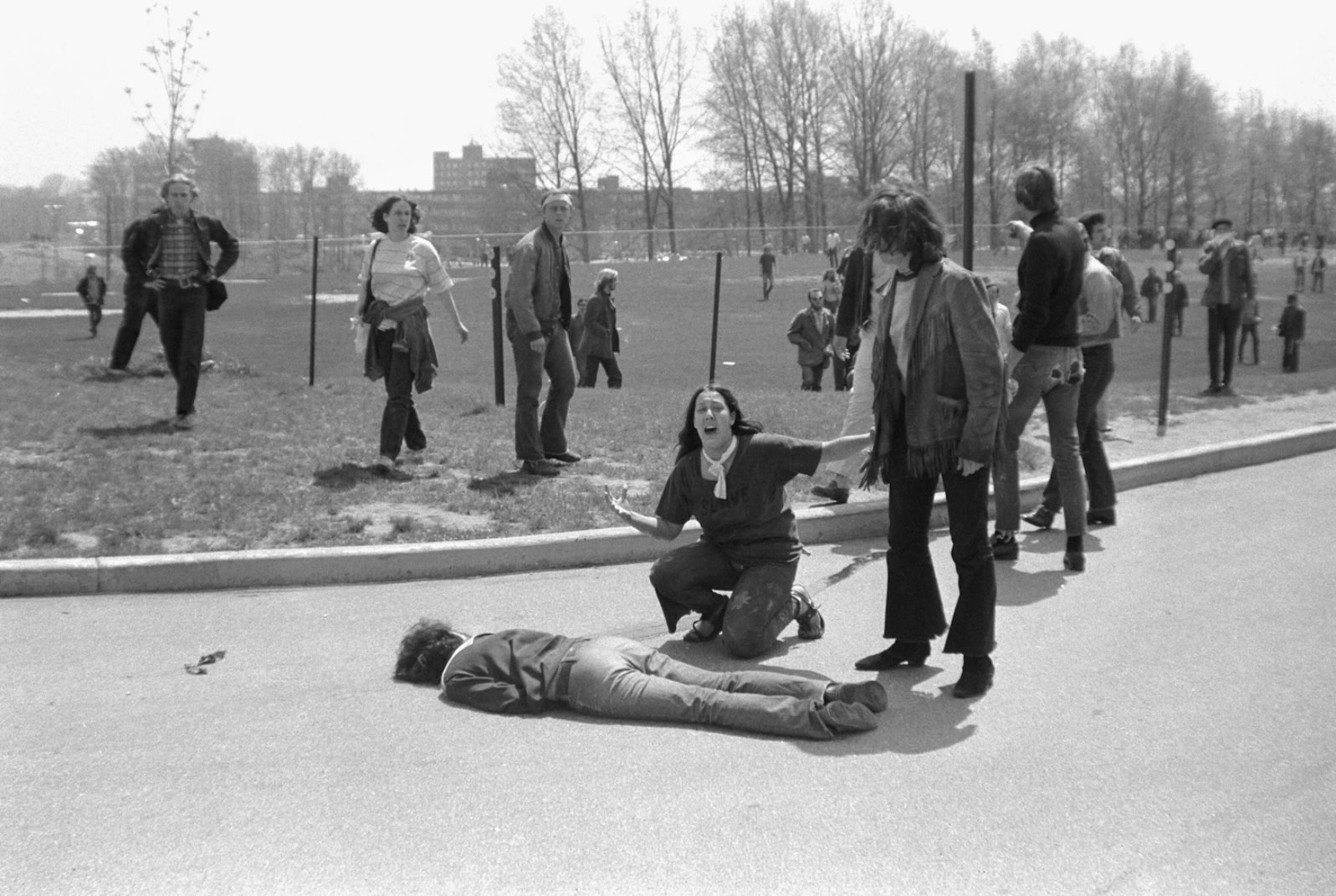

Kent State University, Ohio, 1970 . . . at a protest the National Guard approaches minutes before four students are killed. [o]

A couple of years ago I wrote an article published in these pages, 'Ten Songs that Made a Difference.' In it I presented a list of songs that strongly contributed to the culture of equality and respect for diversity.

Many of the songs are American, none are Canadian. This is because my main criterion was based on the degree to which these songs have an anthemic quality – meaning, songs that derive their impact from being sung collectively by large groups during highly visible public demonstrations. In contrast, Canadian protest songs are typically performance songs, presented by individuals or groups in concerts or on recordings.

Arguably, the first American protest songs were spirituals that emerged during the slavery period in the American south. These songs were typically sung in groups using call and response, and often included hidden meanings that protested slavery. While there were some slaves in Canada, two factors mitigated against the formation of a unified protest song culture.

First, in contrast to American plantations, in Canada the typical work process was individual labour: domestic servitude, work on farms, or in hotels and taverns — places where conditions were not conducive to collective singing. Second, slaves in Canada were a more heterogeneous group than in the US; they consisted of Africans from diverse backgrounds but also of a large number of Indigenous peoples.

We begin with a song that emerged from the Lower Canada rebellion of the 19th century.

The Songs

Un Canadian Errant / A Wandering Canadian (1842)

Words by Antoine Gerin-Lajoie, music from an old French folk song, 'Je Fais un Maitresse.'

In 1837, the French inhabitants of Lower Canada rose up against decades of British rule and the result was death for many of the rebels, exile for others. In 1839 a sixteen year old boy named Antoine Gérin-Lajoie was in Cap-Diamant, Quebec. This was a major departure point for the exile of rebels, and he was present when a group of chained men were forced aboard a ship bound for Australia.

Three years later, the scene inspired him to write “Un Canadien Errant,” a song that has become a poignant lament for the separation from one’s homeland — adopted by peoples beyond the Lower Canada rebels and their descendants. A prime example is the Acadians of Nova Scotia; because they resisted the demand to swear allegiance to the British crown, from 1755 to 1763 many were hung and others were deported. The song beautifully evokes their own anguish and remains a salient part of Acadian culture.

Here is the first stanza [with English translation]:

Un Canadien errant [A wandering Canadian]

Banni de ses foyers [Banished from his homeland]

Parcourait en pleurant [Travelled, weeping]

Les pays étrangers [Through foreign lands]

Among those who have recorded the song are Leonard Cohen, Ian and Sylvia, and Paul Robeson. The following version by soprano Mireille Asselin was performed at an Amici Music Concert with the Toronto Chamber Ensemble — featuring David Heatherington, cello.

Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream (1950)

Words and music by Ed McCurdy

The author of this song, Ed McCurdy (1919-2000), was born in the US and started early in a musical career that included folk music, vaudeville acts and gospel singing. In 1948 he married a Canadian and moved with her to British Columbia where he became the host of his own radio show on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). His success in Vancouver translated into a popular CBC children’s show, and then one devoted to folk music. Among the guests who appeared on his show were Oscar Brand, Pete Seeger and Josh White.

In 1950, five years after the horrendous bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Ed McCurdy wrote “Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream.” The song presents a utopian vision of a world without war: “Last night I had the strangest dream I ever dreamed before . . . I dreamed the world had all agreed to put an end to war.” Recorded by many artists, including Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, and Simon and Garfunkel, it has achieved iconic status well beyond its initial purpose of a powerful condemnation of nuclear weaponry. Sung in dozens of languages, in 1980 it became the official theme song for the US Peace Corps.

Here it is sung by its author.

Universal Soldier (1964)

Words and music by Buffy Sainte-Marie

After much consideration I have opted to include Buffy Sainte-Marie’s “Universal Soldier” in the list. Although her Canadian citizenship and Indigenous identity have recently been questioned in a detailed investigative documentary by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, from which a controversy has erupted, up to a month or two ago her strong stature in Canadian musical society was assured. Clearly these revelations bring up the question of how we reconcile our regard for the value of an artist’s work with how they carry on their lives as individuals in society. For me, it comes down to this: I am personally proud of Buffy Sainte-Marie the artist and revel in her legacy of humanitarian pursuits, activism, and song-writing. As a result I find it impossible to suddenly renounce her accomplishments.

Sainte-Marie’s career features several highly touted works on the unjust treatment of Indigenous peoples. Among these are “Now that the Buffalo’s Gone” (1964) and “My Country ‘Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” (1964). Her activism was not confined to Indigenous issues. In 1963, after observing soldiers returning from the Vietnam War, despite the U.S. government’s insistence that American troops were not involved in the fighting, she wrote “Universal Soldier,” which I believe to be one of the most original and compelling of the anti-war songs that emerged during the Vietnam conflict. The target in most such songs is typically the government, but here it is every citizen and every soldier. According to Sainte-Marie we all bear responsibility for legitimizing war and perpetuating it:

He's the Universal Soldier and he really is to blame

His orders come from far away no more

They come from here and there and you and me

And brothers, can't you see?

This is not the way we put an end to war

In the following video, Sainte-Marie contextualizes the song by describing the role of young people in the protest movements of the 1960s. She also speaks about what led to her writing the song.

Black Day in July (1968)

Words and music by Gordon Lightfoot

Born in Orillia, Ontario in 1938, Gordon Lightfoot is arguably one of Canada’s greatest songwriters. A fine guitarist (particularly on 12-string) with a distinctive baritone voice, he has created many memorable songs, including “Early Morning Rain,” “If You Could Read My Mind,” “Canadian Railroad Trilogy,” and “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald," to name a few.

The month of July 1967 produced one of the most deadly civil disturbances in American history, the Detroit riots. It began with an after-hours police raid on a bar frequented by African Americans. All were arrested, fuelling the anger of a large group of onlookers outside the bar, many of whom bore witness to a long history of police brutality in the city. Wide scale looting and arson followed the arrests, leading to the involvement of the US army and the Michigan National Guard and five days of chaos and violence. Dozens were killed and almost 1200 injured.

‘Black Day in July’ was released in 1968, three months before the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. The lyrics depict in graphic terms the deadly role of law enforcement:

In the streets of Motor City is a deadly silent sound

And the body of a dead youth lies stretched upon the ground

There’s gunfire from the rooftops

And the blood begins to spill

Thought to be contributing force to racial conflict, the song was banned on many radio stations in the US, despite its call for peace near the end:

And you say, how did it happen?

And you say, how did it start?

Why can't we all be brothers?

Why can't we live in peace?

Gordon Lightfoot died in Toronto at the age of 84 earlier this year.

Ohio (1970)

Words and music by Neil Young

On April 30, 1970, U.S. President Richard Nixon confirmed that the Vietnam War was to be expanded into neighbouring Cambodia. A wave of student protests followed on many university campuses, including Kent State University in Ohio. On May 2, Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes called in the Ohio Army National Guard to restore order; the next day as the protests accelerated, he said this at a press conference: “We've seen here at the city of Kent especially, probably the most vicious form of campus-oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups . . . We're going to use every part of the law enforcement agency of Ohio to drive them out of Kent. . . They're worse than the brown shirts and the Communist element. . . They're the worst type of people that we harbour in America. . . They are not going to take over the campus.”

On May 4 the National Guardsmen opened fire on the protesters, killing 4 students. Nine others were wounded. Widespread anger manifested in demonstrations and strikes across the country. Millions of university students walked out on a myriad of campuses, focusing attention on both First Amendment rights and on the moral and ethical issues associated with the war.

Photo by John Filo. [o]

Young wrote the lyrics to “Ohio” while a member of the group Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young after reading a Life magazine article on the shootings that included photographs of the killings.

Here is an account of the writing and recording of the song by Graham Nash.

The song captures Young's simmering outrage at this incident. It also underlines his passion for truth and social justice that comes through so strongly in the repetition of the phrase, “Four dead in O-hi-o...”

Big Yellow Taxi (1970)

Words and Music by Joni Mitchell

Roberta Joan 'Joni' Anderson was born November 7, 1943 in Fort Macleod, Alberta, becoming Joni Mitchell after marrying folksinger Chuck Mitchell in 1965.

Mitchell’s songs are distinguished by their lyrical brilliance and musical innovation, perfectly aligned with her instantly recognizable sweet, throaty mezzo-soprano voice. Her fusion of folk, rock, jazz and classical music makes her a uniquely creative artist. Her career is noteworthy for experimentation with open guitar tunings and quartal and quintal harmonies.

Despite the lament at the end for a personal relationship gone bad, “Big Yellow Taxi” is largely an environment protest song bemoaning the disastrous effects of deforestation and pesticides: “They paved paradise to put up a parking lot . . . they took all the trees and put them in a tree museum . . . hey farmer, farmer, put away that DDT now.” — just a few examples of her ability to write clever, enduring and simple yet profound lyrics.

I Pity the Country (1971)

Words and Music by Willie Dunn

Willie Dunn (1941-2013) was a Mi’kmaq singer, musician, filmmaker and activist. Unlike the musicians above, he never achieved mainstream success. This was partly due to his political activism, which led to periodic imprisonment, and partly to his refusal to compromise his artistic principles. Dunn rejected a lucrative offer from Columbia Records to tour with Glen Campbell; they had suggested, as a marketing ploy, that he smash his guitar on stage as an act of anti-establishment rebellion. Despite his marginal status in the music industry he managed to leave a rich legacy of artistic accomplishments.

In 1968 he wrote a powerful anti-colonial song, “The Ballad of Crowfoot,” which is featured in his documentary film with the same title. Both the song and film decry colonial injustices and urge Indigenous Canadians to engage in widespread political activism. The film was the first in National Film Board history to be directed by a person of Indigenous descent, and it won many awards, including a Gold Hugo award in 1969 at the prestigious Chicago International Film Festival. In 1971, he wrote “I Pity the Country,” a continuation of his forceful critique of colonialism and racism:

I pity the country

I pity the state

And the mind of a man

Who thrives on hate

If I Had a Rocket Launcher (1983)

Words and music by Bruce Cockburn

Bruce Cockburn (1945-) picked up a guitar at age 14 and later studied piano and jazz composition. As a consummate activist he has espoused causes relating to Afghan refugees, child soldiers, Indigenous land claims, deforestation, and the elimination of landmines. Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians (2001) compares the passion of his activism to that of one of the most influential protest singers of the 1960s: “No artist since Phil Ochs has taken such strong political stands."

In 1983 Cockburn was touring a refugee camp in Mexico when he was informed that Guatemalan helicopters had earlier attacked the defenceless refugees. “If I had a Rocket Launcher” was his angry response to this event:

Here comes the helicopter — second time today

Everybody scatters and hopes it goes away

How many kids they've murdered only

God can say If I had a rocket launcher...I'd make somebody pay.

O Siem (1995)

Words and music by Susan Aglukark

Susan Aglukark’s (1967-) career embodies two major intersecting elements: activism and music. The former began when her family moved to Nunavut where she developed an enduring passion for the North: “I loved looking out into the bay and seeing the white go on forever, feeling the power of that white expanse and its seeming vulnerability and purity.” (Canadian Geographic magazine). This passion is evident in her role as a major advocate for northern communities. Among the organizations she is affiliated with are Arctic Children and Youth Foundation, RCMP National Alcohol and Drug Awareness Prevention Program, and Inuit Tapirisat of Canada, which is dedicated to the preservation of Inuit culture. In 2012 she began the Arctic Rose Project in order to enhance the effectiveness of food banks serving northern communities.

Her love of music began in early childhood when she was invited by her father, a Pentecostal minister, to sing in the church choir. She began playing guitar in bible camp and within a few years became a well-known singer in Inuit circles. Her first album, Arctic Rose, appeared in 1992.

Her fusion of Inuit folk and pop music has endeared her to Canadian music fans. In 1995, with her release of “O Siem,” she became the first Inuk to appear on the Canadian music charts.

“O Siem” is an ebullient welcome for loved ones and a call for civility and diversity and the eradication of walls of racism and intolerance.

Fires burn in silence

Hearts in anger bleed

Wheel of change is turning

For the ones who truly need

To see the walls come tumbling down

O Siem, we are all family

O Siem, we're all the same

O Siem, the fires of freedom

Dance in the burning flame

Harperman (2015)

Words and music by Tony Turner

From 2006-2015, conservative politician Stephen Harper was the Prime Minister of Canada and received a lot of blowback from progressives for his zealous right-wing policies — part of a global trend against so-called populist leaders. During this period he was the target of musical protests from a wide range of artists in various genres, including rock (“Stealing All My Dreams,” Blue Rodeo), rap (“What’s Up Steve?,” The Caravan) and children’s music (“I Want My Canada Back,” Raffi).

The most effective of the anti-Harper compositions was a song called “Harperman” by Tony Turner. Although it doesn't have the universal appeal of the previous songs, I include it because it is one of the very few Canadian songs to approach anthemic status: that is, sung collectively by large groups during public rallies.

Inspired by his experience planting trees and learning about forest management, Turner became a scientist, eventually working for Environment Canada, a federal government department.

In 2015 he wrote “Harperman,” a forceful critique of Harper and his policies. The song asks a series of questions — Who controls our parliament? Who squashes all dissent? Who has slashed the budget of our public broadcaster? Who says our future lies in oil sands? The answer is invariably the same: “Harperman, Harperman,” and the chorus urges a quick exit from the political stage: “Get out of town (town, town), don’t want you round (round, round). Harperman, it’s time for you to go.” After it was posted on YouTube it immediately received nearly a million views.

A controversy for the artist followed. The song was seen as a violation of the maxim of public servant impartiality and Turner was suspended from his government job, pending a formal investigation. Near retirement, he made the decision to retire rather than wait for the results.

On September 17, 2015, the song was sung simultaneously by hundreds of people on Parliament Hill and in cities across the country. On Oct. 19, Stephen Harper was defeated.

See other articles by Stephen Richer on the history of protest music

• The Protest Legacy of African American Spirituals, Part 1

• The Protest Legacy of African American Spirituals, Part 2

• Ten Songs that Made a Difference

STEPHEN RICHER is a Professor Emeritus at Carleton University where he was head of the Sociology and Anthropology Department. He has been a folk and protest singer since his teens. He now teaches courses on the history of protest music at Carleton’s Institute for Lifelong Learning Program. He lives in Ottawa. Stephen's lecture on the life and influence of Pete Seeger can be seen here.

Comments

Thanks for all your…

Thanks for all your background on these songs I grew up with, as well as introducing me to Susan Aglukark and Tony Turner. How about another article on the current songs of protest?

Thanks for this Sharon. Re…

Thanks for this, Sharon. Regarding current protest songs, you might check out my article on the protest legacy of spirituals, Part 2. In it I make the argument that Rap is the major contemporary vehicle of protest.

Excellent article, Stevie. I…

Excellent article. I too still love the music of Buffy Sainte-Marie, so I am glad that you included her, and especially her video. I never knew that Ed McCurdy became an adopted Canadian, and "Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream" remains one of the most poignant songs for me. I also had never known the history of how "Un Canadien Errant" came to be. Thank you.

Hey there Stephen! Enjoyed…

Enjoyed…

Enjoyed very much your series here, especially the pieces on 'Ohio', 'Black Day in July', and 'O Siem'... and the extremely interesting links you provided. Also, your take on the current controversy over Buffy Sainte-Marie's heritage: a most thoughtful way to think about it, and resolve the quibbles, about her place in it all.. Bravo, Stephen. A job well done!

Good piece, excellent…

Good piece, excellent selection of songs, and the Buffy issue well handled.

If you decide to compile a more modern list, you might want to consider Ian Robb’s “They’re Taking It Away” — wonderfully singable, endlessly adaptable, hilariously pointed.

An excellent suggestion…

An excellent suggestion, Shelley. I have been a fan of his for a long time.

What a marvellous essay,…

Most of these songs bring back such vivid memories. I totally agree with your rationale for including Buffy Sainte-Marie. Of course, that opens the door to the larger issue of cancel culture. Perhaps a topic for your next essay? Keep up the great work.

Thank you so very much for…

Thank you so very much for this inspiring article and reminding us of some remarkable Canadian talent.

I do remember the shocking days of Kent State and the Democratic National Convention; and the political times evoked from other songs. Your background was invaluable.

Aren’t Canadians (or those who are possibly wanna-be Canadians) grand? Give us social injustice or a reason to protest and we waste no time in crafting heartfelt, moving or satirical and remarkably lasting songs.

I hope we get the chance to play some of these songs together again soon.

A marvellous article written…

A marvellous article written by a marvellous man.

What a wonderful way for you…

What a wonderful way for you to share your passion, Stephen. It is informative, entertaining, and it comes at a time when we badly need a voice to express our hope in the face of so much hate and violence. Bravo!

Thank you Stephen your…

Thank you, Stephen, for your treatise. It really resonated with me, having in my life a long history of protesting and resistance to the injustices I’ve observed in the world and the society I have lived in. And having a great love of the troubadours who have championed the causes I’ve believed in. May the search for justice and peace never end.

Thanks for another great…

Thanks for another great article. I heartily agree with your sentiments regarding Buffy Sainte-Marie and am glad to see her included here. But I was equally happy to be introduced to a few artists I was unfamiliar with, most notably Willie Dunn (who reminds me of Fred Neil....). Considering its relatively small population, Canada turns out a remarkable number of really great authors and singer/songwriters. I'd love to hear your thoughts as to why that is. Maybe your next essay?

Thanks for the question…

Thanks for the question, Julie. I think we need more reliable data to be able to conclude that Canada is indeed producing more musical artists and authors per capita than other countries. What I am confident in saying is that we are certainly pulling our weight!

Great article! I love…

Great article! I love getting the Canadian perspective.

Add new comment